Merely a Madness?

Probing the Boundaries

Series Editors

Dr Robert Fisher

Lisa Howard

Dr Ken Monteith

Advisory Board

James Arvanitakis

Simon Bacon

Kasia Bronk

Jo Chipperfield

Ann-Marie Cook

Phil Fitzsimmons

Peter Mario Kreuter

Mira Crouch

Stephen Morris

John Parry

Karl Spracklen

Peter Twohig

S Ram Vemuri

Kenneth Wilson

A Probing the Boundaries research and publications project.

http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/probing-the-boundaries/

The Making Sense of Hub

‘Madness’

2012

Merely a Madness?

Defining, Treating and Celebrating

the Unreasonable

Edited by

Daniela Fargione and Johnathan Sunley

Inter-Disciplinary Press

Oxford, United Kingdom

© Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012

http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/

The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network

for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and

encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and

which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary

publishing.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior

permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland,

Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom.

+44 (0)1993 882087

ISBN: 978-1-84888-101-3

First published in the United Kingdom in Paperback format in 2012. First Edition.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Daniela Fargione and Johnathan Sunley

Part I

Rationalising Madness

Madness and Civilisation: The Paradox of a False Dichotomy

Noëlle Vahanian

Part II

ix

3

Madness as a Philosophical Problem in Hegel

S. J. McGrath

19

Can We Understand Madness Without Rationalising It? Sense,

Common-Sense and Nonsense in Psychoanalytic Explanation

Johnathan Sunley

35

Institutionalising Madness

The Irony of E.A. Poe’s Lunatick Asylum

Daniela Fargione

51

Madness and Punishment during Apartheid: Insane, Political

and Common-Law Prisoners in the Western Cape

Natacha Filippi

73

Part III Narrating Madness

‘Their Lives A Storm Whereon They Ride’: The Affective

Disorders, Writing and the Case for Neurodiversity Studies

Stephanie Stone Horton

97

An Unsound Mind in an Unsound Body: Physical Manifestations

of Mental Distress in Women’s Madness Narratives

Katarzyna Szmigiero

119

When Love and Madness Converge: A Cross-Cultural Analysis

of Lovesickness

Nicoletta Fazio

145

Part IV

Performing Madness

Madness: An Escape or a Dead End?

Iwona Bojarska

171

Saving the Dreams from the Nightmare, the Light from the

Shadows: Titzina’s and Marta Carrasco’s Theatrical

Lessons on Madness

Núria Casado-Gual

185

‘Because the Drummed Rhythm Was Seven…’

Richard McGregor

205

Acknowledgments

Daniela Fargione wishes to thank her daughter, Giulia, for her

cheerful and complicit attitude while putting up with her mother’s

artistic and literary madness.

Special thanks to Rob Fisher, Daniel Riha and Gonzalo Araoz for

offering us the opportunity to critically discuss the thorny issues

included in this volume.

Introduction

Daniela Fargione and Johnathan Sunley

The 3rd Global Conference on Madness was held in Oxford in September 2010.

It brought together some thirty people – among them artists, writers, academics,

students and survivors/consumers of mental health services – from eight countries,

each with their own perspective on this fascinating if also troubling human

experience. Over several days they discussed what it has meant to be mad at

different times and in different cultures. What kind of category is this anyway? Are

those who suffer from ‘madness’ in some sense ill or simply distressed? Are they

cursed or inspired? Dangerous or in danger? And what can they expect from the

rest of society? Is it treatment or understanding they need? Cure or care?

In terms of the search for answers to these questions, 2013 will be a significant

year. Almost certainly the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders will add to an already long

list of supposedly abnormal behaviour patterns that count as clinical conditions.

Prior to publication of the first version of this manual in the 1950s, it had always

been recognised that there was more than one way to be mad. But now we are told

that there are in fact several hundred discrete syndromes, each with its own

symptom check-list and presumed underlying brain pathology. Excessive appetite

or shyness or sadness: nowadays any of these might be regarded as a medical

matter and diagnosed accordingly.

One word that does not appear in the pages of the DSM or in modern mental

health discourse more broadly is madness. Today this tends to be seen as an

unscientific, backward-looking term. Maybe ‘madness’ does have something of a

bad reputation. But does that justify trying to eliminate it from our lexicons

entirely? Is that not equivalent to pretending that we can easily and painlessly

remove it from our psyches using the latest anti-depressant or other medication?

Certainly Shakespeare did not run away from the term. Madness is a major

theme in his plays. The title of this book is drawn from one of them, from a scene

in As You Like It in which the ‘love-shaked’ Orlando has the nature of his

condition explained to him by Rosalind:

Love is merely a madness; and I tell you, deserves as well a dark

house and a whip as madmen do; and the reason why they are not

so punished and cured is, that the lunacy is so ordinary that the

whippers are in love too. 1

The point being made is that to a greater or lesser extent we all take leave of

our senses when we fall in love. And since at one stage or another during our lives

we all fall in love, we all know what it is to take leave of our senses. In other

words, you do not have to be Lady Macbeth or King Lear to know what madness

x

Introduction

__________________________________________________________________

is. By the same token, experiencing some degree of madness does not make you a

character in Shakespeare. It is a state of mind that is both extraordinary and

everyday.

The chapters in Merely a Madness? Defining, Treating and Celebrating the

Unreasonable are grouped in four sections. These correspond to some of the ways

– there are many others – in which madness has historically pressed itself on

society’s attention: as a strange, threatening phenomenon that requires explanation

by priests or philosophers in order for us to feel remotely comfortable with it; as a

sickness in need either of treatment or restraint (or both); as a source of creativity –

as well as an obstacle to it; and as a kind of encounter that can be hard to put into

words yet is well-suited to representation on stage or in music. In total there are

eleven chapters. These are based on papers presented at the 2010 conference that

were subsequently revised and extended by their authors, drawing on contributions

from other participants. This is in-keeping with the aims and ethos of InterDisciplinary.Net, under whose auspices the conference series on madness is

organised and this volume is published.

Philosophers have been trying to make sense of madness since the time of

Plato. Their perspectives are the focus of the first section of this book, titled

‘Rationalising Madness’. Plato himself exalted our human capacity for reason. But

the surging desires and emotions that sometimes endanger it he regarded as no less

human. That is why he also welcomed the intervention of the divine in the form of

Eros: to mediate between our two sides as well as to lead us in the direction of the

transcendent.

In her contribution to this section, Noelle Vahanian argues that Descartes

pushed philosophy towards becoming much clearer about madness. But he did so

at a price. In place of the complexity and subtlety of pre-modern thinking about

human nature, he put forward a series of polarities – between mind and matter, soul

and body, reason and unreason. These have remained extremely influential up to

our own day, even if we would now rather speak about ‘mental disorders’ (which,

paradoxically, are held to be primarily biological in origin) than madness. There is

a false dichotomy at work here, says Vahanian. And she approvingly cites

Erasmus, the humanist who became one of the leading figures of the Reformation

due to his unsparing criticism of the church, yet who still celebrated the folly of

faith as being that much more sensible than the folly of reason alone.

S. J. McGrath explores post-Enlightenment theorising about madness. Hegel

had first-hand experience of this subject. His sister was diagnosed with hysteria

and had to be cared for by the German philosopher and his wife. In his view,

madness and reason were not opposites. He understood madness rather as reason

derailed – or possibly diverted. For according to Hegel, madness is a stage through

which the mind (the ‘feeling soul’ as he terms it) necessarily passes on its way to

becoming capable of distinguishing the inner world from the outer. Some people

Daniela Fargione and Johnathan Sunley

xi

__________________________________________________________________

remain stuck in this stage, however, and do not acquire a sense of reality as others

do. ‘For Hegel’, writes McGrath, ‘the insane is the cousin of the normal mind’.

McGrath sees Hegel’s theories of madness as anticipating those of Freud on a

number of key points. Freud considered himself a scientist rather than a

philosopher. And yet as Johnathan Sunley observes in the final chapter in this

section, the contribution made by psychoanalysis to our understanding of fullblown delusions as well as more manageable neuroses is also a philosophical one.

Psychopathology is all around us, Freud claimed. He found evidence of it in

dreams, jokes and everyday actions for which on one level we seem to have a

perfectly good reason. The issue is not that humans – or rather some humans – lack

reason. On this Freud agreed with Plato. What makes us all fundamentally

irrational creatures, the founder of the ‘talking cure’ argued, is the overwhelming

need we have to repeat in the present emotional conflicts from our pasts. It is as

though we want to remind ourselves who we are – when what we actually do is

express who we were. No wonder we are inclined to feel at odds with ourselves.

The view taken throughout much of history, nonetheless, has been that those

suffering from one form or another of madness need to be kept apart from the rest

of us. Whether this has been for their benefit or ours’ is a question that surfaces

repeatedly in the second section of this volume, ‘Institutionalising Madness’.

This begins with Daniela Fargione’s analysis of one of the least well-known of

Edgar Allen Poe’s short stories ‘The System of Dr Tarr and Prof Fether’. Published

in 1845, this satirical tale follows the story of an unnamed narrator who visits a

madhouse in the south of France. His insistence on meeting the inventor of a

radical new method used to treat mental disturbances (here called ‘the system of

soothing’ and echoing the celebrated ‘moral treatment’ pioneered in postrevolutionary France by Philippe Pinel) leads him to several ‘distractions’. While

reflecting the desire of his contemporaries for more humane care for the insane,

Poe’s short story is scathingly ironical in the view it takes of the practice of

compulsory institutionalisation that was fast becoming the norm both in America

and Europe. After questioning the supposed unproductiveness of the ‘lunatick,’

Fargione shows how Poe’s irony is also directed against the hypocritical

philanthropic intentions of an inadequate government.

With the agreement of the South African department of correctional services,

and thanks also to the generous collaboration of (mostly) anonymous interviewees,

Natacha Filippi was able to conduct groundbreaking research in the archives of

Pollsmoor prison and Valkenberg mental hospital. Her chapter concentrates on a

crucial moment in the history of South African apartheid, from the 1960s to the

democratic transition, and explores how incarceration and disciplinary actions

represented powerful tools in the imposition of a circumscribed subjectivity on

alleged inferior populations. Categories of criminal, political and mental deviance

were deliberately conflated. Filippi concludes that the criminalisation and

punishment of Blacks and Coloureds during these years was legitimised through

xii

Introduction

__________________________________________________________________

the support these policies received from the country’s psychiatric establishment.

She also shows how difficult it has been for post-apartheid governments in South

Africa to escape the burden of these policies as they have attempted to forge a

completely new approach to mental health.

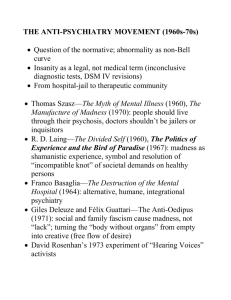

In most parts of the Western world, the era labelled by Michel Foucault (rightly

or wrongly) as the ‘great confinement’ began coming to an end in the 1960s. The

asylum soon became a thing of the past. The last half-century has witnessed a

comparable revolution in the way mental disorders are defined and diagnosed. At

least within the medical profession, nowadays these tend to be viewed as

organically-based conditions similar in most important respects to the diseases or

accidents that affect our bodies. For both types of illness, physical and

psychological, pharmaceutical interventions are usually the preferred means of

treatment.

Two of the chapters in the book’s third section, ‘Narrating Madness’, offer

opposing perspectives on these developments. For Stephanie Stone Horton, the

symptoms of clinical depression or bipolar disorder are as disruptive and

devastating as they always have been. She writes about her own experiences as a

journalist, sitting in front of a computer-screen for hour after hour, waiting for a

single word to emerge through the storm in her brain circuitry. But now that we

have a better understanding of the causes of these conditions, Horton proposes, we

should reclaim our agency and celebrate the extraordinary company – famed poets,

artists and composers throughout the ages – in which our faulty genes or misfiring

neurotransmitters put us. In the words of the French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan:

‘Not everyone who would be mad, could’.

Katarzyna Szmigiero is not so sure. In her chapter, she returns to the problems

created by Descartes’s mind/body split. The authors of such classic examples of

the ‘misery memoir’ genre as Prozac Nation or Wasted are clearly no strangers to

suffering. But is the source of their distress their minds or their bodies? Szmigiero

observes that in nearly all cases the unhappiness of these female writers is

expressed in the relationship they have with their appearance, with food or with

sex. Her conclusion is as follows: ‘Listening to one’s body with respect and

heeding its needs for rest, affectionate care, nourishment and intimacy, may be an

effective tool in tackling mental distress’. The problem is that contemporary

psychiatry has only updated the terms of Cartesian dualism: our anguish is still

located in our heads – if no longer in our minds then in our brains.

What of the heart? As we have seen, for Shakespeare there was nothing madder

than love. But as Rosalind says, ‘the lunacy is so ordinary’. That is why, in

Elizabethan England, even if you found yourself as ‘love-shaked’ as Orlando, you

did not expect to be ‘punished and cured’ like most madmen. Not all cultures have

been either so indulgent or lenient, however. In the third chapter in this section,

Nicoletta Fazio describes how in the medical systems of the ancient world

‘lovesickness’ was thought to rival melancholy and mania as a form of illness. To

Daniela Fargione and Johnathan Sunley

xiii

__________________________________________________________________

some extent this view was carried over into Christianity. Fazio finds support for

her hypothesis in the text (and associated imagery from the period) of the

Renaissance epic Orlando furioso. Its eponymous hero is driven quite literally mad

by the force of his unrequited love. The end he comes to is in many respects a

shameful one and a dire warning to anyone tempted to copy his example. A similar

fate might have been expected to befall Majnun, who was an equally popular and

emblematic character in Islamic literary culture at about the same time. He too falls

head over heels in love with an unobtainable woman. Yet he manages to preserve

his mind. During these centuries, Fazio argues, Muslim philosophers and

physicians were just as concerned by the malady of ‘lovesickness’ as their

Christian counterparts. But within some of the more mystical strains of Islam, even

passionate love was perceived as having a liberating dimension to it – and this is

what saves Majnun.

The fourth and last section, ‘Performing Madness,’ is made up of three chapters

that explore possible ways of representing psychological distress through various

art forms: literature, dance, drama and music. Iwona Bojarska’s chapter

concentrates on Alan Ayckbourn’s Wildest Dreams, a play in which a group of

people choose to escape from their everyday lives by entering into a role-playing

game that gives them new identities. The author shows how the artificial world

they withdraw into transforms itself: from a protective refuge where they face their

personal inadequacies into a veritable madhouse. Probing the liminal space

between sanity and insanity, Bojarska demonstrates the ‘healthy’ side of mental

illness. But she also warns of the precariousness of this condition and of the risks

involved in slipping beyond a safe limit.

The second chapter in this section discusses the representation of madness in

two avant-garde theatrical experiments from Spain. Núria Casado-Gual argues that

choreographer and dancer Marta Carrasco and the theatre company Titzina have

through their performances helped audiences arrive at a broader and less

judgmental understanding of mental illness. In some ways madness is completely

unsuitable to being staged. ‘There is nothing really comical or lyrical in being mad’

says the author. But Casado-Gual also suggests that these two artistic

representations enable us to gain a new vision of madness through an analysis of

our ever-changing personalities as reflections of an unstable historical moment and

fluid cultural contexts.

The last chapter of this section and of the book analyses German composer

Wolfgang Rihm’s work Tutuguri, a Poème dansé inspired by Antonin Artaud’s

poem of the same name that was written while he was incarcerated in an asylum at

Rodez. Richard McGregor argues that Rihm’s encounter with this poem marked a

turning-point in his stylistic development. After showing the relation between the

imaginary and the symbolic in Artaud’s work, the author pinpoints Rihm’s

difficulties in translating this act of spontaneous creation into a notated musical

language.

xiv

Introduction

__________________________________________________________________

Working on these chapters and revisiting the themes and debates of this

conference, what strikes us as editors is that the aesthetic difficulty faced by Rihm

could be said to be similar to the challenge faced by anyone who loses their reason.

It is not that they no longer have anything meaningful to say. That is clearly not the

case. The question is whether they are still able to express themselves in a

‘language’ (of whatever kind) that others can hear. For that to be possible, of

course, those they communicate with will need to have a good ear. Otherwise they

may miss what is being said. And there is perhaps nothing more likely to leave one

tone-deaf in this regard than the loud clashing between ‘reason’ and ‘unreason’

which is the usual background noise to discussions of madness.

Is that distinction ultimately a sustainable or profitable one? We are grateful to

our authors – as well as to all participants in the 3rd Global Conference on Madness

– for bringing this question into such clear focus, and we hope that readers of this

book will be helped by it to arrive at their own conclusions. In her chapter,

Stephanie Stone Horton presents a quotation from Foucault in which the French

philosopher nimbly overturns the terms of this divide: ‘I was mad enough to study

reason; I was reasonable enough to study madness.’ 2 For our part we would like to

end this introduction with an aphorism from Nietzsche that in our opinion goes

right to the heart of the matter: ‘There is always some madness in love; but also

some reason in madness.’ 3

Notes

1

W Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act III, Scene II, in The Portable Shakespeare

(Viking Portable Library), Penguin Books, New York, London, Victoria, Toronto,

Auckland, 1977, p. 515.

2

M. Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of

Reason, trans. R. Howard, Vintage Books, New York, 1988, p. 30.

3

F. Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, trans. T.

Common, 7 November 2008, Viewed 1 October 2012. <http://gutenberg.org/files/

1998/1998-h/1998-h.html>.

Bibliography

Foucault, M., Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of

Reason. Trans. R. Howard. Vintage Books, New York, 1988.

Nietzsche, F., Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None. Trans. T.

Common. 7 November 2008. Viewed 1 October 2012. <http://gutenberg.org/

files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.html>.

Daniela Fargione and Johnathan Sunley

xv

__________________________________________________________________

Shakespeare, W., As You Like It. Act III, Scene II. The Portable Shakespeare.

(Viking Portable Library). Penguin Books, New York, London, Victoria, Toronto,

Auckland, 1977.