Honesty, lying, deception and related notions are of particular

advertisement

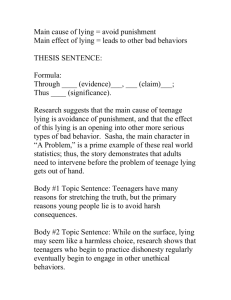

Bruton Draft 4/12/07 Honesty, Part 1 Honesty, lying, deception and related concepts are of particular importance in business ethics. Most economic transactions and relationships depend, at least to some degree, on information received from others. This dependency, however, often provides an opportunity to shade the truth to one’s own advantage. Overstating a product’s benefits and neglecting to mention its faults can increase sales; a bit of “creative” accounting can make a company more appealing to investors than it otherwise would be; fudging a bit on a résumé can help to land a desirable job, and so forth. Before examining lying and deception in business contexts, we will first define these concepts and consider some ethical issues relating to them in a variety of everyday situations. A. Lies and Deception. 1. Lies a. Lying defined A lie is a statement made deliberately to mislead others which is believed to be false by the person who makes it. The statements in question can be made verbally or in writing, or in some cases by gestures. To say that a statement is made “deliberately to mislead others” is to say that the person making it believes it to be untrue although he or she intends it to be accepted by the recipient as true. So understood, lying differs from simply saying or writing false things in two respects. First, the intent is crucial. Someone who is acting a part in a play or film, writing a novel, or telling a joke may say many things which she does not believe to be literally true, but she is not thereby lying. In cases like these, one intends not to deceive, but to entertain or amuse. Some novels, movies and plays aim not just to entertain, of course, but may aspire to express subtle truths about life or give the audience a new perspective on the human condition. In any event, the intent is not to convince readers or listeners that what is being said accurately describes actual states of affairs. The liar, though, aims for what he or she says to be accepted as true. Second, what matters is whether the liar believes that what is said is false, not whether it is in fact false. False statements are not lies if they are made as the result of simple mistakes or confusion. If someone is just mistaken, she lacks the intent to deceive, but also, she does not believe that what she is saying is false. It is false, but she doesn’t know it. On the other hand, if A intends to deceive B by telling her an untruth, and yet, unbeknownst to A, what is said turns out to be true, this is still a lie. To make this point clearer, consider the following example. Suppose that as I am leaving my apartment to walk to school, my roommate asks me where I put the keys to my car. I am worried that he may try to take my car for spin, so I tell him that I have my keys with me in my backpack, even though I remember leaving them on my desk. Suppose, however, that after I packed my backpack my other roommate slipped my car keys into my backpack without telling me. (Perhaps he did this because he assumed I would want to keep the keys away from the other roommate, the car-swiper.) In this scenario, what I tell my untrustworthy roommate is actually true, because the keys are in my backpack. But have I lied? Yes. My intent is the same as if my other roommate had not intervened. I believe that what I’m saying is false, even though it happens to be true.1 Summing up: One lies when one makes a statement believed to be false with the intent to deceive.2 3A1a. Questions 1. Name two different ways of saying something untrue without lying. 2. Consider an incident in which President Ronald Reagan, minutes before a broadcast, not realizing that the microphone he was speaking into was “live,” said, "My fellow Americans, I'm pleased to tell you today that I've signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes." What Reagan said, of course, was not true - was it a lie? 3. Can you think of an example of something that you have heard referred to as a lie that does not meet the definition just given? Can you think of something that would not be a lie that nonetheless meets the definition just given? b. Are All Lies Wrong? A curious fact about lying is that if you ask people whether or not it is morally wrong or unethical almost everyone will say that it is, and yet it seems that people lie quite regularly. We lie for various reasons: to avoid embarrassment, to gain an advantage, to impress, to avoid responsibility, to maintain a façade, to help others or to spare their feelings, and to gain control. One recent study found that most of us lie once or twice a day and over the course of a week are dishonest with about 30 individuals that we interact with personally. The same study found that college students lie to their mothers one out of every two times they speak to each other – dating couples lie to each other in about a third of their conversations.3 And lying appears to be no less common in business than in personal relationships. A consultant for some of America’s largest public corporations says his polls reveal that 20% - 30% of middle managers had written fraudulent internal reports.4 A recent survey found that more than 95% of participating college students were willing to tell at least one lie to a potential employer to win a job, and that 41% had already done so.5 Another example of a lie that happens to be true is given by Fried: "For instance, a gov’t official might state that one of our citizens has been arrested and ill-treated in some foreign nation. He might make this statement to justify a policy hostile to that foreign country. The official has no information and does not believe that this arrest has taken place. Unknown to him, however, there has been such an arrest. I would say that this official has lied." Charles Fried, Right and Wrong, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978), p. 58. 2 This squares with the definition given by Fried, who maintains that “a person lies when he asserts a proposition he believes to be false.” (Fried, p. 55) Compare also, “A lie, strictly defined, is a statement, verbal or non-verbal, of a proposition that the speaker believes to be false, but that the speaker intends the audience to take as a proposition the speaker believes to be true.” Larry Alexander and Emily Sherwin, “Deception in Morality and Law,” Law and Philosophy 22(5) (September 2003), p. 395. 3 The study was conducted by Dr. Bella DePaulo, described in Allison Kornet, ??, Psychology Today, Vol. 30 Issue 3 (May/June 1997), p. 53. 4 Kenneth Labich, “The New Crisis in Business Ethics,” Fortune Vol. 125 No. 8 (April 20, 1992). 5 Valerie Frazee, “Students Tell Tales to Win Jobs,” Personnel Journal Vol. 75 No. 10 (October 1, 1996). 1 How should we understand the fact that although people apparently believe that lying is wrong, they nonetheless engage in it quite frequently? Perhaps this inconsistency is the result of simple hypocrisy, but perhaps there is more to it than that. Let us examine more seriously the common thought that lying is morally wrong. What do we mean when we say that? One way to take the claim that “lying is wrong” is to suppose that this is just an abbreviated way of saying that all lies are wrong, or that the rule that “One ought never tell a lie” is true. This interpretation gives us what we may call the absolutist position on lying. Is the absolutist position plausible? Several eminent thinkers in western thought have defended it. Aristotle is often read as having condemned all lies. The Christian theologians St. Augustine and St. Aquinas both maintained that lies are inherently sinful, and their views on lying were very influential on the official doctrines of the Catholic Church.6 Another hard-liner, Kant, argued that it is impermissible to lie even to save a friend from a would-be murderer. But it is not hard to think of cases that make the absolutist position difficult to accept. Imagine, in a kind of “Schindler’s List” scenario, that someone is hiding Jews in her basement in Nazi Germany. Nazi soldiers knock on her door and ask if there are any Jews in the house. If she responds to the soldiers’ question truthfully, the Jews will be sent to death camps. Would it be wrong in this circumstance to lie to the soldiers? (It is likely very risky, but that is a different issue.) Other cases of this form - where a significant moral good can be achieved only by lying - are easy to find. Imagine that the President of the United States is planning to order a military attack on a dangerous foreign country and has been holding regular discussions with his generals as to how best to do it. Suppose reporters then ask the President if he is considering military maneuvers against this foreign country. Assume the circumstances are such that there is no easy way for the President to duck the question without the risk of tipping his hand. If he wishes to maintain the element of surprise in the attack, the President might - quite justifiably, it seems - simply lie and say, “No.” The absolutist position seems flawed by its complete obliviousness to context. A different way to take the common thought that “lying is wrong” is to suppose that it means that lying is presumptively wrong. This, which we might think of as the moderate position on lying, maintains that most lies are wrong, but that lying can be morally permissible or even morally required when there is an especially weighty justification for it. Such a position might include the thought that lying is intrinsically or inherently wrong, but deny that the intrinsic wrongness of lying entails that lying is wrong is every possible circumstance. (The idea, then, would be similar to Ross’s claim that there is a prima facie duty of fidelity.) The obvious difficulty facing the moderate approach involves getting clearer about under exactly which sorts of circumstances lying is permissible. Presumably the moderate would want to say that the two cases just described - the cases involving the “Schindler’s List-type scenario and the President’s war plans - would count as justified 6 In fairness, it should be emphasized that Augustine and Aquinas both held that lies can differ notably in their moral severity. Like these two, many who defend the absolutist position on lying do so at least partly on religious grounds - one of the Ten Commandments is that “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.” Exodus, 20:16, RSV; see also Deuteronomy 5:20. Traditional Jewish thought understands this commandment fairly narrowly, as forbidding giving false testimony against another in a court of law or similar proceeding. Catholics and many Protestant denominations tend to interpret this commandment more broadly. lies. But what about cases where the aim in lying is not to help others, but to help oneself? Suppose that I am being accused of a murder that I did not commit, but the circumstances surrounding the crime and my relationship to it are such that if I truthfully answer the detectives’ questions about where I was at the time of the murder, what I was doing, and so forth, that the detectives will surely think that I did it, as will even a reasonable jury. Am I morally justified in lying to the detectives? For that matter, aren’t some lies to benefit others justified even when the stakes are relatively small? Imagine you are guests at a dinner party and the hostess asks you if you liked the fish soufflé that she served. Honestly, you could barely get down enough of it so as not to make it obvious that you hated it, but knowing that it was made from a family recipe that the hostess is very proud of, you smile and say that you enjoyed it very much. Is that wrong? Reflections on cases like these may lead us to think that an even more permissive or tolerant approach is warranted. The moderate’s claim that lying is presumptively wrong was intended to imply that lying is wrong except in (relatively) rare circumstances, but perhaps lying is warranted in a great many situations. Maybe lying is permissible - as an Act Utilitarian would have it - whenever the good consequences of the lie outweigh the bad. The Act Utilitarian position amounts to a rejection of the thought that there is anything intrinsically wrong with lying. There are good reasons, however, against being this permissive. In some cases, it seems that lies can be wrong even when the likely consequences of them are on the whole beneficial. Suppose that, tragically, a depressed college undergraduate takes his own life by over-dosing on pain medication. His mother, a devout Catholic, is distraught by the thought that her son might not go to heaven, since Catholics typically believe that committing suicide precludes that kind of eternal reward. Consumed by her grief, she goes to speak with the psychiatrist that she knows her son had been seeing before his death. She asks the psychiatrist whether her son had been contemplating suicide and explains that she is convinced that the over-dose must have been an accident. The psychiatrist, however, knows that the son had been contemplating suicide for a long time and finds it highly unlikely that the son’s death was unintentional. But the psychiatrist also knows that by lying to the distressed woman, that he might allow her to continue to cling to her hopes.7 Should he lie? I would think not. The situation is in some ways similar to other kinds of truth-telling decisions that sometimes confront doctors: whether or not a terminal patient should be told that his or her condition is incurably fatal. Suppose, in order to make the lie a tempting option, that the doctor knows that the patient has only a short time in which to live, and that the doctor has good reasons to think that a particular patient will not be able to handle the truth very well. “Doctor, is my condition fatal?” the patient asks. I would say that the patient has a right to the truth, even though he or she might be in many ways worse off for knowing it. (The case seems importantly different if the patient has made it clear that he or she doesn’t want to know the truth about his or her condition.) Similarly, anguished as she might be by the truth, it would be wrong to deny it to the mother of the young suicide victim. This is so even though on a straightforward consequentialist reckoning, lying might well have better overall effects. This case is derived from one discussed by Thomas E. Hill, Jr., “Autonomy and Benevolent Lies” in Autonomy and Self-Respect (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), pp. 25 - 42. 7 Doubts about a permissive stand on lying do not stem from tragic circumstances alone. Suppose you decide that you must fire Carlos, a hardworking and amiable but ineffective employee. Though Carlos’ work ethic is all that you could ask for, he has repeatedly made costly mistakes. But you know that letting Carlos go will be devastating to him. What should you tell him as to why he is being fired? You might think that you would do Carlos a favor by attributing the decision falsely to necessary budget cutbacks, circumstances beyond your control, or some other kind of well-intentioned fib. But by masking the truth, you may well prevent him from coming to grips with his shortcomings. Perhaps this was not his line of work. Or it may be that he will see through the well-meaning lie and will be insulted as well as hurt. In any event, one can owe another person the truth even when the truth is painful to both give and receive. Though much more can and should be said about the circumstances in which lying is justified, let us close this section with a cautionary point and some quick generalizations. The cautionary point is that it is a mistake to confuse the view that lying is (generally) wrong with the view that one should always tell the whole truth. In a great many circumstances, it is wrong to lie but telling everything that one knows would be needlessly cruel and insensitive. No moralist, to my knowledge, has ever maintained that honesty requires complete disclosure at all times. The generalizations are that whether or not a lie is justified will depend on, 1) what is at stake in the situation, 2) whether it seems that the would-be victim of the lie has a “right to know” the truth, 3) the liar’s motive, 4) whether there is any reasonable way to accomplish the lie’s intended purpose without lying, and no doubt other factors as well. 3A1b. Questions 1. Am I right that it would be wrong for the psychiatrist to lie to the mother of the suicide victim? How about the doctor and the dying patient? (Concealing bad news from a sick person, by the way, is one of two justified exceptions to a general rule against lying that Mill mentions in Utilitarianism.) 2. Aside from the lying-to-the-detectives scenario described above, can you think of another situation where it would be justifiable to lie to benefit oneself? Is it ever justifiable to lie for the sake of money? 3. Which of the three views described above seems to you most plausible - the absolutist position, the moderate view, or the more permissive (simple) Utilitarian principle? c. Why is Lying Wrong? There are, of course, perfectly good prudential or self-interested reasons against being dishonest in most circumstances. Many times the benefits of deception are only temporary, and its long-term effects may leave one worse off than if one had been honest from the outset. A striking example of this sort is the story of George O’Leary. In 2001, the University of Notre Dame hired O’Leary to be its head football coach, one of the most prestigious jobs in all of college athletics. According to his résumé and biographical information he submitted to the school, O’Leary had a master’s degree in education from New York University and had been a three-year letterman on the football team at the University of New Hampshire. Neither claim was true. Notre Dame was soon embarrassed that these fabrications were part of the biographical sketch it released to the media when he was hired. When the truth came out, only five days later, O’Leary was forced to resign. It turns out that he had been embellishing his credentials in this way at least as far back as his first college coaching job, at Syracuse University in 1980, and had never corrected these misstatements. After this public humiliation, O’Leary ultimately became the head coach at the University of Central Florida, a much less glamorous school than Notre Dame. While examples of this sort show that lying and other means of deception are often unwise - “honesty is the best policy,” as the saying goes - the moral and ethical case against dishonesty cannot rest on self-interested or prudential considerations. For one thing, not all wrongful deceptions work against our long-term interests, and there are cases where honesty too can work to our disadvantage in the long run. But even were this not so, the fact that lying is harmful to the liar would not explain why it is morally objectionable. Many things that are not in our self-interest are not immoral. There are a variety of moral arguments that can be given against lying, but three popular and promising lines of argument are particularly worth mentioning. As many authors have noted, there is a very strong connection between truth-telling and trust. Bok writes, “trust in some degree of veracity functions as a foundation of relations among human beings; when this trust shatters or wears away, institutions collapse.”8 Her point is that trust is a crucial social good, and that lying is wrong because it weakens trust. So stated, the argument, broadly speaking, is consequentialist. Many deontological accounts emphasize the wrong to the victim of the lie. Because knowing the truth is crucial to being able to effectively control one’s life and make reflective choices about it, denying someone the truth is an affront to his or her personhood. Lies violate the victim’s autonomy and wrongfully treat him or her merely as a means to some further end, even when that end is, as in some of the cases considered above, the victim’s own good. A final kind of argument against lying is that it degrades the liar herself. Kant, who was never one to minimize the seriousness of lying, claims that the liar “throws away and, as it were, annihilates his dignity as a human being.” Another representative of this point of view is the French Renaissance thinker Montaigne, who writes, "I do myself a greater injury in lying than I do him of whom I tell a lie." 3A1c. Questions 1. Cingular Wireless offers a new service called "Escape-A-Date" which allows customers to program their cell phones to ring at pre-established time. The idea is that a cell phone call can give the receiver a handy opportunity to cut short an uncomfortable or boring first date. Would it be morally acceptable to use this service to "Escape-A-Date"? 2. In order to supplement his salary from a local grocery store, Antoine starts a small lawn-mowing business in his neighborhood. His insists that his customers pay him in cash, and he does not report this income on his income tax. Antoine figures he is doing nothing wrong, since taxes are already taking a big bite out of his paycheck from the grocery store. Is he right? 3. Suppose that Hudson’s, a discount store that specializes in selling merchandise liquidated by failed retailers, receives a shipment of merchandise from a music store. 8 Sissela Bok, Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life (?? 1978), p. 31. Jeff, a drummer who is in the market for a new crash cymbal, hears about Hudson’s new stock and finds just what he has been looking for. The sign on display promises 40% off the lowest marked price; the tag on the cymbal reads $229.00. When the cashier rings up his sale, however, she apparently misreads the tag and rings up 40% off of $22.90. Jeff notices the error but says nothing and ends up with a great new cymbal for less than 14 bucks. He figures that it is the cashier’s responsibility to ring up his sale correctly and he has done nothing wrong. Is he right? 4. Your boss calls Saturday morning. You are supposed to have the day off, but don’t have any firm plans. The boss, though, explains that there’s a crisis at the office and she badly needs you to come in to work. You don’t want to go in, but don’t have a good excuse so you make one up - is that wrong? 5. A man was laid off from his position as a graphic designer and technical writer for a software firm. He immediately began looking for a new job. The résumé he sent out accurately describes his skills and experience but includes an important untruth: it claims that he continues to work for his former employer. “It is much, much, much harder to get a job if you are not already employed,” the man explains. “I have two kids to feed an am not about to risk my livelihood on some trivial moral imperative. Outside of this situation, I am a 100 percent morally, ethically upstanding person.” The man understands that there is a decent chance that his lie will be discovered. A simple phone call to the former employer to confirm dates of employment would reveal the lie and end his chances at any firm that bothers to check out his credentials in this way. Still, he feels that this is a risk that he must take. Has he done anything wrong?9 6. You are an older worker (in your 40s) in search of a job. Though you had a successful career as a computer programmer, a recent downturn in the technology sector has left you without a job. After months of pounding the pavement looking for work as a programmer, you’ve given up; companies are simply not hiring, and that is unlikely to change any time soon. So you decide to make a career change. You’ve always been interested in marketing and try to get hired in a marketing department. The problem, though, is that you have no experience in marketing and are qualified only for an entry level position. However, companies generally prefer to offer entry level positions to younger, recent college graduates. Moreover, companies are unlikely to hire you on at an entry level position when they learn of your last salary and graduate degrees in computer science; companies will likely judge you as “over-qualified” and will think it unlikely that you would remain for long in any position they could offer you. So on your applications you decide to lie about your last job’s salary at Silicon Systems Inc. claiming that you only made half of what you actually made - and completely omit mention of your Master’s Degree from Stanford. Have you done anything wrong? 7. Your company requires employees to complete a web-based compliance course in order to familiarize employees with the relevant governmental regulations and company policies. Employees log on to the website using their employee identification numbers and the computer records their progress. Noticing that you have completed the course, your manager, Peter, comes to you and asks you to complete the course for a star salesperson, Rebecca, who has only finished a third of it. (Peter would give you Rebecca’s ID number, apparently with Rebecca’s permission.) Peter explains that Rebecca has been so busy that she simply has not had the time to finish the course, and 9 Jeffrey L. Seglin, “Necessary Lies,” New York Times, October 3, 2004 (??). that finishing it would cost her at least a day’s worth of potentially valuable sales calls. Besides, Peter explains, Rebecca “knows all of that stuff anyway.” Is it okay for you to finish the course for Rebecca?10 8. Your co-worker misses work because she has to appear in court for reasons that she would prefer that her boss did not know about. She phones in sick, but the boss suspects a ruse and asks you why Jeannette is gone. Though the boss is usually understanding and forgiving, you know that Jeanette would prefer that the boss not know that she's in court or for what reason. If you say that she’s sick or that you do not know, you will be lying. What do you tell the boss? 9. Ms. Bailey is the founder and chief executive of BlueSuitMom.com, a start-up website aimed at executive mothers. Because new websites easily come and go and are often not taken seriously, Bailey decides that she needs to convey the impression that her company is better-funded and more established than it in fact is. She adds the names of freelance helpers and part-timers to the biographies in her business plan (neglecting to mention that these people are not full-time members of the staff), and she uses fake email addresses to give the impression that there are various people staffing nonexistent departments. To impress prospective clients, she tells them that she has executives from companies like Blockbuster and Alamo on her staff when in reality she has received only free consulting services from people at these firms. "I knew what I was capable of doing," says Bailey, looking back. "I just had to sell them on what we were going to be." Did Bailey do anything wrong when, for example, she referred people to cathy@BuleSuitMom.com in human resources or debby@BlueSuitMom.com in accounting when there are no such people and no such departments at her company? 11 2. Deception a. Deception defined In one sense, a deception is just something that misleads, that is, something that causes false beliefs. We might, for example, describe an optical illusion as deceptive or a runner as deceptively fast (i.e., a runner who is going faster than she looks to be). More typically, however, we mean by ‘deception’ the causing of false beliefs intentionally. In this sense, deception shares with lying the fact that it is deliberate. But there are two big differences between the concepts of lying and deception. The first is that deception is the much broader term - one can deceive in many more ways than one can lie. Hiding behind a wall can deceive someone into thinking that you are not in the vicinity, but you have not thereby lied. Lying requires some kind of assertion or statement, while deception does not. Furthermore, some kinds of deceptions occur by omission, which is to say, as a result of what is not done. One such example can be seen in a court case in which a witness was asked whether he had ever maintained a Swiss bank account. The man answered that his company had had a Swiss bank account for six months. If, as was apparently the man’s intention, the jurors took his answer to mean that 10 11 Jeffrey L. Seglin, "Time to Draw the Line," New York Times, June 3, 2006 (??) Jeffrey L. Seglin, "When Truth Takes a Stretching Class," New York Times, August 19, 2001 (??). he had never had never had such an account, they would have been deceived, for he had in fact maintained Swiss accounts. He did not, however, lie.12 The second big difference is that deception tends to function as what philosophers refer to as a “success term.” This means that in order for A to have deceived B, B must have come to have false beliefs as a result. An attempted deception that fails to produce false beliefs is just that - a mere attempt. Lying is not like this, though. In order for A to have lied to B, it is not necessary for B to believe the lie. B may see through it or may know that A is an inveterate liar and can never be trusted. Still, A may have lied. b. Is Deception Wrong? Because deception can occur in so many ways, no well-known philosophers have held, unlike lying, that it is always wrong. In fact, most philosophers have maintained that there is a serious moral difference between lying and deception. For example, despite his notoriously rigoristic opposition to lying, Kant commented that it would be acceptable to pack one’s bags in the presence of others so as to create the (false) impression that one was about to embark on a trip. Kant’s thought, apparently, was that the deceiver is not morally responsible for the inferences others draw about her behavior and that, unlike a lie, deceiver who does not lie is not being untrue to herself. While it seems clear that the moral status of lies and deceptions can differ in some cases, it is important not to hastily conclude that deceptions are always of lesser moral import. When Bill Clinton said he was never alone with Monica Lewinsky at the White House, what he claimed was probably technically true. The White House is a large building, and whenever the President is there, secret service agents and others can be expected to be present, although often not in the same room as the President. The fact that what Clinton claimed was technically true, however, hardly exonerates him for what he said. He clearly hoped that people would draw the inference that he and Lewinsky were never alone together in the same room, which, as it turns out, was quite false. Since the intent in a deception can be the same as in a lie, and since the intent is in large measure what makes lying morally objectionable, it would seem that deceptions can be as wrong as lies, even if that is not always true. 3A2b. Questions 1. “On Sept. 26, 2001, [Ken] Lay was touting Enron’s stock to employees in an online chat. He said he’d been buying in previous months. Public records showed that was true, to the tune of about $4 million. But Lay had sold $24 million of Enron’s stock to Enron in the previous two months. He didn’t mention that. Under SEC rules at the time, Lay had to disclose public sales or purchases within 10 days - but could wait until February 2002 to disclose transactions with Enron itself. Lay should have told his employees about those sales and explained that he was selling for personal reasons but nevertheless believed in the company. Instead, he misled his employees - and the financial markets - by omission.”13 Was Ken Lay’s omission any less wrong than if he had outright told his employees that he had not sold any Enron stock in the previous two months? 12 This example, from Bronston v. United States, 409 U.S. 352 (1973), is described by Alexander and Sherwin, p. 407. The Court held that the witness had not committed perjury. 13 Allan Sloan, Newsweek, July 19, 2004, p. 50 2. Suppose that an oil company, after running exploratory tests on an adjacent property, comes to believe that there is a good chance that a well in farmer Jones’ field could strike oil. So a landman - an employee of the oil company responsible for securing a lease and mineral rights to Jones' property - approaches the farmer. The landman does not disclose the results of the exploratory tests to Jones out of fear that Jones would drive a harder bargain by insisting on a greater share of the profits that a successful well might bring. Instead, the landman emphasizes that no decision on drilling has been made, and that Jones will be paid $2,000 for simply signing the agreement, even if no well is ever drilled. Is this ethical?