Chapter 11 Notes - Herbert Hoover High School

advertisement

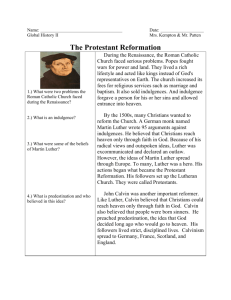

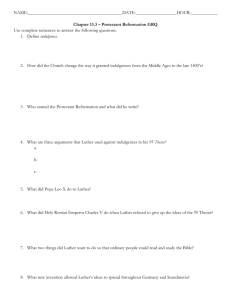

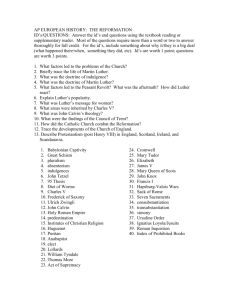

Chapter 11 - The Reformation The Protestant Reformation did not just happen. Rather it was the result of profound social, political and religious forces that led up to a religious rending [tearing apart] of Western Christendom that will never [in all likelihood] be healed. The Protestant Reformation began as an attempt to reform the Catholic Church mostly by priests who opposed what they perceived as false doctrines and ecclesiastic malpractice—especially the teaching and the sale of Indulgences or the selling and buying of clerical offices. But there were also many non-clerical groups that saw the Church as a powerful institution which threatened their prerogatives and freedoms. Guilds and merchants of the rising middle class in the imperial cities in Germany felt that the Church was blocking their expanding businesses. In addition many people, rich and poor, were disillusioned because they felt that the Church was not a loving parent but a greedy bully. Finally, there were many kings who envied the church’s power and wealth – and wanted a share for themselves. All these factors led to a rising resentment that (both hypocritically and sincerely; clerical and lay) criticized the church for being too worldly. In many ways the Reformation was a rejection of the humanism of the Renaissance and its new education with its moral failings. Some scholars have called the Reformation the last gasp of medieval piety. So in the two hundred years leading up the life of Martin Luther, we have seen the founding of the loyal-to-the-church Dominicans and Franciscans along with the rebellious Lollards, Hussites, Albigensians and Waldensians. These were the first calls for thorough reform and should have been a wakeup call for the papacy and Church leaders but they went unheeded. And it is supremely important to remember that no one in the year 1500 could possibly have imagined the shattering effect of the Reformation, which would destroy the unity of Christians to our very day. As we noted in the last Chapter, Northern European Humanists were drawn to religious sincerity and piety more than the Italian Humanists; and we also saw how Erasmus and Northern humanists urged a return to a more simple and heartfelt religion. One interesting group we noted was the Netherlands based Brothers of the Common Life, also known as the Modern Devotion. Founded in the 14th century by Gerhard Groote (1340-1384), they ran a kind of boarding school run by brothers that did not take formal monastic vows but lived a religious life of prayer and contemplation. The brothers (and there were houses for sisters) did not wear distinctive religious dress nor abandon their secular jobs. They were educators, copyists, publishers and advocates for poor children, especially boys who were preparing for the priesthood. Erasmus studied under their care and formulated his philosophy of Christ from what he learned from the brothers. Thomas à Kempis, a German monk and writer, summarized their philosophy in his famous book, The Imitation of Christ (De Imitatione Christi). Two of his famous quotes from the still popular book are: At the Day of Judgment we shall not be asked what we have read, but what we have done; and Man proposes, but God disposes. Luther and the Shattering of Western Christendom Martin Luther was born in 1483 in Germany to a successful Thuringian miner. He was educated at Magdeburg by the Brothers of the Common Life. In 1501, he entered the University of Erfurt. He was a brilliant student and by 1505 had been awarded both his bachelors and masters degrees. Shortly afterwards, he was caught outside in a lightning storm and (in the terror of the moment) promised God that, if is life was spared, he would join a monastery. Although his father wanted him to be a lawyer, Luther was drawn to the study of Scripture. He soon joined the Augustinian religious order and spent three years in the Augustinian Monastery (The Order of the Hermits of St. Augustine) at Erfurt. In 1507, Luther was ordained a priest and later went to the University of Wittenberg, where he lectured on philosophy and the bible, becoming a powerful and influential preacher. So charismatic was his preaching that large crowds came just to hear his sermons. 1|Page In 1510, he was sent to Rome on business for the monastery. While he was there, the laziness and corruption among the clergy appalled him. Among the abuses he saw was the sale of church services and especially indulgences. (In medieval theology, it was believed that, although God forgave sins, sinners still had to be punished. Indulgences were prayers or other rituals to remit some of that punishment. It shocked Luther that church officials sold the indulgences simply to raise money.) When Luther saw the abuse of selling Indulgences and other church services, he considered it a shameless mockery of what the Christian religion should be. In the fourteenth century it had been common for people to pay a small sum for an indulgence, but the papacy, eager for money, kept raising the scope of granting indulgences. In 1343, Pope Clement VI proclaimed a Treasury of Merits which was an infinite reservoir of good works in the church’s possession which could be dispensed at the pope’s discretion. From this treasury, the church sold Letters of Indulgence which made good works of satisfaction on behalf of the souls of those who paid for the Indulgences. In 1476, Pope Sixtus IV declared that Indulgences could be purchased for a person’s friends or relatives or whoever in purgatory, thus reducing their time of suffering. Pope Julius II shamelessly had indulgences sold to raise money to build a new St. Peter’s Basilica and in 1517 Pope Leo X revived the practice of a Plenary Indulgence which would erase all punishment in purgatory for the living or the dead. The most famous of the Indulgence peddlers (sellers) was Johan Tetzel, a Dominican preacher, who crisscrossed Germany selling indulgences to frightened townspeople and peasants. His most famous pitch line was As soon as a coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs. After his return to Wittenberg, Luther’s indignation at the sale of Indulgences and the selling of other Church services grew and grew. He became a doctor of theology in 1512, but his mind became increasingly hostile to the corruption in the Church. So he began to preach more and more his doctrine of Justification by Faith, that is, that Christian salvation is won by faith, not by works. (Re: James: I will show you my faith by my works). So on October 31, 1517 (the year Leo X started granting plenary Indulgences) Luther drew up a list of 95 complaints, his Ninety Five Theses, and nailed them to the door of the Cathedral of Wittenberg. Luther was particularly shocked that Tetzel was selling Indulgences for unrepentant sinners. Within weeks, the Ninety Five Theses had spread throughout Germany, where many, especially Christian Humanists who desired reform in the Church, welcomed them. Luther, a prolific writer, continued to attack the abuses in the Church and soon attacked the Church itself. Erasmus, who originally supported Luther, broke with him when Luther moved from an attack on the sale of Indulgences to an attack on the Roman Church itself. Luther advocated the closure of monasteries, the translation of the bible from Latin into German, and an end to priestly and Episcopal authority (i.e., bishops but especially the pope). He also attacked the doctrine of Transubstantiation, the Sacrifice of the Mass, the celibacy of the clergy (i.e. allowing married clergy), denial of the cup to the laity (i.e., allowing the people to drink from the consecrated wine from the chalice like the clergy), and held that two sacraments, Baptism and the Lords Supper, to be authentic sacraments. Most importantly, he maintained that the Bible alone [sola scriptura] was the source of all authority in the Church. (The Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox Churches claim that authority comes from Scripture, Tradition (i.e. church councils) and Reason). Luther’s ideas were widely embraced by many German humanists and princes; thus Luther – willingly or unwillingly – became a central figure in an already budding German cultural movement against foreign influence. Luther was summoned before the superior general of the Dominican Order of Augsburg to give an account of his radical teachings. But in January 1519, before he could appear or sanctions (legal charges) be drawn up against him, the emperor Maximlian died. This was a crucial and fortunate turn of events for Luther and his supporters because Maximilian’s death turned attention away from Luther to the contest for a new emperor. Francis I of France, supported by the pope, challenged the grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella, Charles I of Spain to be the new emperor. 2|Page The nineteen year old Charles, a Hapsburg (Maximilian was his paternal grandfather), was the more natural candidate and he was supported by the wealthy Fugger Banking House of Augsburg, which paid off (i.e. bribed) the seven imperial electors. The most important of these was Frederick III [the Wise] of Saxony, who was Luther’s lord, protector and supporter. So Charles won the election and became the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. In the same month that Charles V was elected emperor, Luther debated a staunchly Roman Catholic theologian, Johan Eck. When Luther had begun to make his views known, Eck was sympathetic and felt they both had much in common but when Eck read the Ninety Five Theses, he accused Luther of fomenting anarchy in the Church and branded Luther a Hussite. This led to a bitter exchange between them. In these disputes with Eck, Luther openly challenged the infallibility of the pope and the inerrancy of church councils, openly asserting the authority of the Bible alone. In 1520, Luther wrote a pamphlet, An Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, in which he urged the German princes to force the Church to reform, especially in curtailing the Church’s political interference and economic power in Germany. In another pamphlet, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, he attacked the doctrine of the Seven Sacraments, arguing that only the Eucharist and Baptism were fully scriptural. In a third pamphlet, Freedom of a Christian, Luther formally taught his doctrine of Salvation by Faith alone [Sola Scriptura]. In 1520, Pope Leo X issued a Papal bull [proclamation], Exsurge Domine [Arise, O Lord], which condemned most (but not all) of Luther’s doctrines and gave Luther sixty days to recant (publically admit he was wrong). Luther publically burned his copy of the bull to show his complete break with Rome. In 1521, Luther, given safe conduct by the emperor, presented his views to the Diet of Worms, which was presided over by the emperor himself. Johann Eck acted as the spokesman (really the prosecutor) for the emperor and ordered Luther to recant his heresies. Luther refused, saying … I am bound by the Scriptures…and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen. Charles had Luther made an outlaw so, for his own protection, his old friend, the Elector Frederick III of Saxony, “kidnapped” and hid Luther in Wartburg Castle for almost a year. While there Luther, using Erasmus’ Greek Bible and the Latin Bible, translated the New Testament into German. Charles V would have liked to have brought Luther to his justice [code for burn for heresy] but he was occupied with dual enemies, Francis I of France and the Ottoman Turks. Charles had responsibilities both as the king of Spain and as Holy Roman Emperor. He needed loyal German troops and so he sought friendly relations with the German princes. Between 1521 and 1529, Spain and France fought four major wars over Italy (part of the series of wars known as the Hapsburg Valois Wars) and so Charles though his representatives agreed at the Diet of Speyer in 1526 that each German state was free to enforce or not enforce the Edict of the Diet of Worms which declared Luther an outlaw. This concession gave the German princes territorial sovereignty in religious matters and gave Lutheranism time to become firmly established in many parts of Germany. Many German princes followed Luther and broke with the Roman Catholic Church, some on genuine religious ground, others because they thought a political advantage could be gained, especially building their own power bases. During the 1520s and 1530s many of the most important German cities (Strasbourg, Nuremberg, Augsburg) along with the Elector Frederick III of Saxony and the Prince of Hesse passed laws prohibiting Roman Catholic religious services and required all services to be Lutheran in doctrine and procedure. By the mid-16th century about half of the German population had adopted Lutheranism and the reformers had launched or were helping to launch Protestant movements in other lands. In the 1530s, German Protestants formed a powerful defensive league, the Schmaldkaldic League, to defend themselves against the emperor and his Catholic forces. 3|Page But during its first decade, Lutheranism almost destroyed itself in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1524-1525. German peasants at first were wildly supportive of Luther because they believed that Luther’s views would help them do away with the burdensome taxes and medieval regulations of the local princes. Peasant leaders saw in Luther’s teaching about Christian freedom, support for their desire to free themselves. They openly appealed to Luther to support them in ending serfdom and giving equal economic rights to all. Luther was sympathetic at first and condemned the tyranny of many princes. But when the peasants revolted in open and violent bloodshed, Luther backed the nobles and urged them to crush to peasants mercilessly; and up to 70,000 peasants were killed. For Luther, Christian freedom meant a spiritual release from guilt and anxiety - not revolutionary bloodshed. A key point to remember is that had Luther joined the peasants, it is likely that Lutheranism would not have survived beyond the 1520s – at least in the form we know it. Zwingli and the Swiss Reformation The Swiss Reformation is linked to Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531), who was born in Switzerland to a farming family and whose father was also a town administrator. Zwingli was sent to Basel to obtain his secondary education where he focused on Latin studies. He later enrolled in the University of Vienna and after that the University of Basel where he received a Master of Arts degree in 1506. His education was a product of Northern humanism and he credited Erasmus more than Luther with having set him on the path to reformation. 1506 was also the year he was ordained a priest and he served as a chaplain to the Swiss mercenaries who were on the losing side at the Battle of Marignano in 1515. It is not surprise that he became a critic of Swiss mercenary service. By 1518, he was also well known for his opposition to the sale of Indulgences and to the many religious superstitions that Erasmus and Luther had already condemned. In 1519 he was appointed Leutpriestertum (people's priest) at the main church in Zurich because of superior reputation as a preacher and writer. He was opposed by some because it was said that he had an affair with a barber’s daughter by whom he had a child. Zwingli minimized the damage by denying paternity and claiming that the woman was a skilled seductress. This is probably part of the explanation that one of his first acts as a reformer was to petition for an end to clerical celibacy. Zwingli used his new position to become the father of the Swiss Reformation. In 1522, he openly broke the Lenten fast which was a reflection of his overarching principle: Whatever lacked literal Scriptural support was to be neither believed nor practiced. And like Luther, he criticized the practices of fasting, transubstantiation, superstitious worship of the saints, purgatory and indulgences, clerical celibacy and the sacraments other than the Eucharist and Baptism. With the agreement of the city government, Zwingli made Zurich the center of the early Swiss Reformation. Zwingli bitterly disagreed with Luther over the nature of the Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. Luther believed that Christ was present but Zwingli believed that Christ was present only symbolically. Luther taught that because Christ was truly human and truly divine, he could be spiritually present (even if bodily absent) in the Eucharist. Zwingli said that Luther was mired [stuck] in medieval superstition and that the bread and wine in the Eucharist were a meal symbolic of the Last Supper. Philip of Hesse (1504-1567) wanted to unite Swiss and Lutheran Protestants and so brought the two leaders (along with other Protestant leaders) together in his castle in Marburg in 1529 to work out their differences. The result was a disaster for Luther and Zwingli. Luther thought that Zwingli was a dangerous fanatic and Zwingli that Luther was a medievalist. Nevertheless the debates, called the Marburg Colloquy, produced fifteen statements of which fourteen were agreed upon; only the nature of the Eucharist could not be agreed upon. 4|Page Despite their differences, the two Protestant factions continued to help each other. The differences also caused a splintering movement forming a semi-Zwinglian group led by Martin Bucer and Caspar Hedio in the non-Lutheran Tetrapolitan Confession in 1530. Moreover, the Protestants faced a more formidable foe in that much of Switzerland remained Catholic. The result was civil war during which there were two major battles, both at Kappel in 1529 and 1531. The first was a Protestant victory which forced the Catholic cantons (states) to recognize the rights of the Protestant cantons. The second (in which Zwingli was wounded and then killed by his opponents when recognized) was a Catholic victory. The treaty which followed, however, recognized the rights of each canton to determine its own religion. Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575), the protégée and son-in-law of Zwingli, became the new leader of the movement and guided its eventual merging into Calvinism. The Anabaptists and Radical Protestants There were also reformers who accused the Lutherans and Zwinglians of being half-hearted in reforming the Church. The most important were the Anabaptists, ancestors of the modern Mennonites and Amish. They particularly objected to infant baptism and taught that only a sincere, knowledgeable adult could understand the Biblical way of life and truly be baptized. Luther and Zwingli also taught that believers must believe for themselves (Luther called it the Priesthood of all Believers) but rejected the Anabaptist position since there was no clear Biblical Mandate against infant baptism. For Luther, Zwingli - and the Catholics - the congregation believed for the infant. Conrad Grebel (1498-1526) was the first person to perform an adult rebaptism in Zurich in 1525. He had worked with Zwingli but was even more radically literal in his interpretation of the bible – and eventually broke with Zwingli, who preferred a more gradual rejection of corrupt religious practices and resisted the headlong rush of Grebel and the Anabaptists. Grebel’s group came to be known as the Swiss Brethren. They declared that since the Bible did not mention infant baptism, it should not be practiced by the church. This belief was subsequently attacked by Zwingli. Consequently, there was a public debate in Zurich and the city council sided with Zwingli. Although Grebel died the next year, this rejection solidified the Swiss Brethren - and also resulted in their persecution by all other reformers as well as the Catholic Church. In 1527, an Anabaptist leader, Michael Sattler, authored the Schleitheim Articles, the first Anabaptist Confession of Faith which not only affirmed the necessity of adult baptism but also the practice of refusing to swear oaths and taking part in secular government. This latter position angered the civil authorities because they saw it as a threat to the social bond of the community and a form of sedition [treason]. Sattler was arrested, along with his wife and several other Anabaptists. All were condemned as heretics. Sattler was burnt at the stake; the men were killed by sword and the women - including Sattler’s wife - were drowned. Thus by 1529, Lutherans, Zwinglians and Catholics all persecuted Anabaptists. To be rebaptized became a capital offense [punishable by death] and thousands of men and women were executed for re-baptizing themselves between 1525 and 1618. The opposite was the case in 1534 when Anabaptists came into the German city of Münster. Led by two Dutch emigrants, Jan Matthys and Jan Beukelsz, they required all Lutherans and Catholics to convert to Anabaptism or immigrate to another place. After the refugees fled, the city was besieged by their opponents and, under this pressure, Münster was transformed into an Old Testament theocracy with charismatic leaders and polygamy. Polygamy (a marriage of one man to multiple wives) was a measure of social control to deal with the problem of so many women that had become widowed. Nevertheless, women who objected were allowed to leave such marriages. Catholics and Lutherans were shocked and the Anabaptists were crushed by Protestant and Catholic forces and the corpses of their leaders hung in public squares till they rotted. After the Münster debacle, Anabaptists became moderate and pacifistic. Menno Simons (1496-1561), the founder of the Mennonites, modeled this non conformist pacifism. 5|Page Another group of diverse and non conformist Protestant dissenters were the Spiritualists. They were mostly isolated individuals who were characterized by a dislike for external, institutional religion. Their only religious authority was the Sprit of God which spoke to them, not in some past revelation, but in the here and now. One of their leaders was Thomas Müntzer, who abandoned Lutheranism and flirted with Anabaptism until he was killed in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1525. Sebastian Franck (1499-1543) was hostile to all organized religion and condemned all religious dogma and teachings. He proclaimed religious autonomy and freedom for every Christian human. Caspar Schwenckfeld (1489-1561) took the Reformation to Silesia. He was influenced by the Spiritualists but developed his own principles such as opposition to infant baptism, war, secret societies, and oath-taking. He fell out with Martin Luther over the Eucharistic presence controversy. His followers were outlawed in Germany and many later immigrated to America. Five churches in Pennsylvania with about 3,000 members are all that remain of his movement. Nevertheless, his ideas influenced Anabaptism and Puritanism in England, and later in the eighteenth18th century, Pietism. Antitrinitarians believed that they were people of commonsense, rational and ethical religion. Most prominent among them was Michael Servetus (1511-1533) who was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and humanist. (He was the first European to correctly describe the function of pulmonary circulation.) He also participated in the Reformation and denied the doctrine of the Holy Trinity and was subsequently burned for heresy (not by the Catholics) but by the encouragement of John Calvin in Geneva. Faustus Sozzini (1539-1604) was an Italian who spent his last years in Poland and one of the founders of Socinanism which became most famous for its Antitrinitarian Christology but also a number of other unorthodox beliefs as well, such as a rejection of Original Sin and that Christ existed as God before he was born as a man. In 1658, his followers were forced to leave Poland and most fled to Transylvania or Holland where they took the name Unitarian and are today the Unitarian Church. Calvinism Switzerland would also be the site of an even more influential Protestant Reformation which would replace Lutheranism as the predominant Protestant force in Europe. The founder of this movement was John Calvin (1509-1564), who was born into a wealthy French family, the son of the secretary of the Bishop of Noyon. Calvin received benefices that allowed him to receive a superior education in Paris where he was ordained a priest and received a degree in law. In the late1520s, he became a follower of the reformers and in 1533, he underwent a conversion experience which brought him to Protestant Christianity. He said it was a difficult move which was only made possible because God made his long-stubborn heart teachable (Calvin wrote: God by a sudden conversion subdued and brought my mind to a teachable frame). This experience led him to sternness and severity on others whom he felt needed conversion so that his theology came to stress the sovereignty of God and man’s obligation to obey God’s will. In 1534, he formally surrendered the benefices which had supported him and dedicated himself to the Reformation. The site of Calvin’s work would be Geneva, Switzerland, where a political upheaval paved the way. In the late 1520s, the Genevans revolted against their prince-bishop and civil authority was placed into the hands of a city council. In 1533, two reformers from Bern, Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) and Antoine Froment (1508-1581), arrived in Geneva and, after much dissension, helped the Protestant party to triumph and in 1536 Geneva officially became a Protestant city. Although Calvin was French, the French monarchy remained so adamantly Roman Catholic that Calvin was forced to flee to Geneva, arriving in 1536. Calvin immediately drew up articles for the governance of the new church as well as a catechism (a summary of teachings) to guide and discipline the people. So pervasive were his measures that he was accused of creating a new papacy. 6|Page Calvin organized a tightly knit religious community and he became a sort of theological dictator. He wrote his ideas in a book called, The Institutes of the Christian Religion. Even more than Luther, Calvin wanted a simplifying of religious services which even passed over into daily life. Calvinists displayed simplicity in their dress and daily living habits. In an age of ornate clothing, they wore simple black clothes, avoided ostentatious living and worshiped in plain and simple churches, which had no pictures, statues, vestments, stained glass and even most musical instruments. Like Luther, Calvin rejected the Catholic hierarchy (the pope, bishops and their authority) and most of Luther’s attitudes towards the ministry and the sacraments. Also like Luther, he believed in Justification by Faith and that all that a Christian needs for authority is the Bible. But Calvin also made his own unique contributions in that he looked to St. Augustine and denied that even human faith could merit salvation. Salvation, according to Calvin, was God’s free gift to those whom God predestinated. These doctrines are called Absolute Predestination and Certitude of Salvation. Absolute Predestination is the belief that God appointed or predestined some people to salvation by his grace, while leaving the remainder to receive eternal damnation for their sins. Certitude of Salvation teaches that God the Holy Ghost works to bring about the salvation of preordained individuals by means of grace and without the cooperation from the individual. Thus Calvin taught that believers may be assured of their salvation through God’s Predestination and by looking into the character of their lives; hence the importance of Calvin’s strict moral codes. Therefore, if Christians believed God's promises and sought to live in accord with God's commandments, then their good deeds (done in response with a cheerful heart) provided proof that would strengthen their assurance (i.e., certitude) of salvation against all doubt. After 1555, Geneva became the refuge of thousands of exiled Protestants who had been driven out of more Catholic areas, especially France, England and Scotland. Those who came to Geneva had to become utterly loyal to Calvin’s theocracy and model all their actions to God’s law - as Calvin saw it. Women gained a new freedom because Calvin’s regulations severely punished men who beat their wives. It is also important to note that Calvinists had a strong Iconoclastic streak reminiscent of the Iconoclasts of the Byzantine Empire in 8th and early 9th centuries - and they destroyed much priceless religious art, including altarpieces, sculpture, paintings and stained glass. Calvinism spread quickly and established strong churches in Scotland, France, the Low Countries and even Hungary. They were most successful in the Netherlands and Scotland where they became the state religion. The Establishment of the Reformation During the 1520s, as Lutheranism was establishing itself in Germany despite the Peasant’s Rebellion, the H.R. Emperor Charles V was distracted by wars with the Ottoman Turks and Francis I of France. But in 1530, he returned to Germany and summoned the Diet of Augsburg which was an assembly of both Lutheran and Catholic representatives. The purpose of the Diet was to solve the growing religious divisions within Germany and reconvert the Lutherans to Catholicism. Charles demanded that the Lutheran princes reconvert and they defied him and forced Charles to listen to a confession of their faith, called the Augsburg Confession. Their defiance proved that the Reformation was too firmly entrenched in about half the German people so that a return to Rome was impossible. In 1531, the Schmaldkaldic League was formed by the Lutheran princes under the leadership of Philip of Hesse and John Frederick, the elector of Saxony. The league won a stalemate with the Emperor who was soon distracted by new conflicts with France and the Ottoman Empire. 7|Page In the 1530s, German Lutherans created Consistories, which were judicial bodies of theologians and lawyers whose purpose was to oversee and administer the new Protestant churches. This led to educational reforms which included compulsory primary education, schools for girls, a Christian humanist revision of the old curriculum and instruction in the new religion. King Christian II of Denmark (r. 1515-1523) introduced Lutheranism into Denmark where it took root and thrived under his successor (and uncle) Frederick I (r. 1523-1533), who himself remained Catholic. But his son, Christian III (r. 1536-1559) made Lutheranism the state religion and all subsequent Danish kings were Lutheran. In Sweden, King Gustavus Vasa (r. 1523-1560) embraced Lutheranism and was supported by the nobility who were anxious to seize church lands. In Poland, Lutherans, Anabaptists, Calvinists and even Antitrinitarians found a place to practice their religions even though Poland remained overwhelmingly Roman Catholic. In 1544, after Charles V made temporary peace with Francis I, he focused on suppressing Protestant resistance within his empire. From 1546 to 1547 in the Schmalkaldic War, Charles and his allies fought the League and crushed them at the Battle of Mühlberg, capturing John Frederick of Saxony and Philip of Hesse. The emperor then established puppet rulers in Saxony and Hesse and issued an imperial law requiring Protestants to reconvert and again become Roman Catholics. Even though Charles allowed some concessions (such as allowing reception of Holy Communion in both bread and wine) many Protestant leaders went into exile. The city of Magdeburg refused to comply and became a center of Lutheran resistance. Even though Charles had crushed the league, the bottom line was that (as at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530) Protestantism was too firmly entrenched to be extirpated [rooted out]. So in 1550, Maurice of Saxony, who had fought with the emperor’s victorious forces at Mühlberg and had been given the title of Elector (in place of the captured John Frederick) was picked by Charles V to capture the rebellious Lutheran city of Magdeburg (1550). But Maurice, who was a Protestant, felt that he had betrayed his faith and seized the opportunity to sign anti-Habsburg compacts with France and Germany's Protestant princes thus changing sides. Confronted by this new resistance and exhausted by three decades of war, the emperor was forced to relent. With the Peace of Passau in 1552, a prematurely aged and emotionally broken Charles V guaranteed religious freedom to Lutherans in the empire which marked his exhausted quest to make his empire Roman Catholic. In 1555, the Peace of Augsburg (not to be confused with the Diet of Augsburg of 1530) made a law the principle cuius regio, eius religio (whose kingdom, his religion), meaning that the prince of any principality determined the religion that would be practiced in his domain. That meant that if a person did not like his prince’s religion, then he had to emigrate. Thus, the division of Western Christendom was permanent. The Peace of Augsburg, however, did not give recognition to Calvinists or Anabaptists. After Münster, the Anabaptists simply formed separate communities but Calvinists remained determined to secure their right to exist, openly practice their religion and shape society as they believed it ought to be shaped. Thus, Calvinism was a much more radical and aggressive form of Protestantism than Lutheranism or Anabaptism. Thus Calvinists (such as the Puritans in England and Huguenots in France) organized in order to spread national revolutions throughout Northern Europe during the latter half of the sixteenth century, as we shall see in the next chapter. The English Reformation The English Church and Monarchy were always more independent of Rome than the continental churches. Edward I (1272-1307) had resisted Pope Boniface VIII’s attempt to tax the clergy. In 1350, Edward III passed the Statute of Provisors which took the election of English bishops out of papal hands and in 1392, the Parliament of Richard II, passed the Statute of Praemunire, which prohibited the assertion of papal jurisdiction over the English king. This independence along with much anticlerical feelings (i.e., the Lollards) and growing humanism set the stage for the English Reformation. 8|Page In the early 1520s, Lutheran ideas were smuggled into England were they were discussed by scholars and future reformers at Cambridge University. One of these reformers was William Tyndale (14921536) who translated the Latin New Testament into English in 1524-25 while he was in Germany. His English New Testament was printed in Germany and taken to England where it quickly circulated. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, King Henry VIII’s chancellor, and Sir Thomas More, Wolsey’s successor, both opposed the growing Protestant movement in England. In 1521, Henry VIII himself wrote The Defense of the Seven Sacraments which was an attack on Luther’s theology. In gratitude Pope Leo X rewarded Henry with the title Defensor Fidei, (Defender of the Faith), which can be seen on English coinage with the letters DF in our century. Luther's reply to Henry’s treatise was, in turn, written by Thomas More, who, many feel, helped Henry compose his Defense of the Seven Sacraments. Lollardy and humanism laid the foundation but it would be Henry VIII who would be the catalyst of the Reformation in England. His father, Henry VII, had arranged a political marriage between his oldest son Arthur and Catherine of Aragon, the younger daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella and aunt of Charles V. Within five months of the marriage (1502) Arthur had died of fever and so Henry, not wanting to return Catherine’s marriage dowry to Ferdinand, paid Pope Julius II for a dispensation to allow Catherine to marry his younger son, and now heir, Henry. The dispensation was necessary because church law forbade a man from marrying his brother’s widow [Leviticus 18:16-21]. The marriage took place in 1509 just after Henry VIII succeeded his father and was - at first - a happy one. The only irritant was a string of still born children with only one child surviving, a sickly child named Mary. It is important to understand that Henry had inherited from his father a terrible fear of dynastic war (from the War of the Roses) and so the thought of a daughter succeeding him was unthinkable. At some point he began, honestly or pragmatically, to believe that his marriage to Catherine had been a sacrilege in eyes of God, which implied that Julius II had not the power to grant a dispensation. So Henry began a campaign to have his marriage annulled so he could marry again and hopefully produce a male heir. He did not want a divorce; he wanted an annulment. [A divorce says that there was a marriage and is dissolved; an annulment that there never was a marriage because of an impediment, in this case because Henry married Arthur’s widow.] So Henry applied to Rome for a dispensation from the dispensation, that is, an annulment. The pope, Clement VII, would have granted the annulment without hesitation (and for a fee, of course) but there was a problem. The year was 1525, the year that Charles V’s mercenaries sacked Rome and took Clement prisoner. [Remember that Charles V was Catherine’s nephew and so he naturally kept the pope from granting the annulment.] Henry lashed out in anger. In 1529, he dismissed Wolsey, who had worked for years to gain the annulment, and, although Thomas More became chancellor, Henry took as his principal advisors Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), soon to be Archbishop of Canterbury, and Thomas Cromwell (1485-1540), both of whom had Lutheran leanings. Their solution was simple: declare the king the head of the Church in England; then the king could solve his own problem. In 1529, Parliament was convened for a seven year session that would earn it the name, the Reformation Parliament. During these years, in a torrent of legislation, Henry was made head of the Church in England. Henry skillfully finessed Parliament making whatever changes he wanted to that Church in England. In 1532, Parliament published a list of grievances against the Roman Catholic Church which ranged from indifference to the needs of the laity to an excessive number of religious holidays. In the same year, Parliament passed the Submission of the Clergy, which placed Canon [church] Law under the king’s control thus making the clergy subservient to the king. This was called the Principle of Royal Supremacy. 9|Page In October 1532, Thomas Cranmer was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury. In January 1533, Henry secretly married Anne Boleyn (who had become pregnant by Henry). In May, Cranmer judged Henry’s marriage to Catherine invalid (he even issued a threat of excommunication, if Henry did not stay away from Catherine) and granted the annulment which allowed the Henry to marry Anne Boleyn. Cranmer then validated the new marriage, crowned Anne Queen of England in June and baptized their child Elizabeth in September. In the same year, Parliament made the king the highest court of appeal of all Englishmen. In the following year (1534), Parliament ended all payments (clerical and lay) to Rome and gave Henry sole jurisdiction over all high ecclesiastical appointments. Parliament also passed the Act of Succession which made Anne Boleyn’s children the legitimate heirs to the throne and the Act of Supremacy which declared Henry the supreme head on earth of the Church of England. Both Thomas More, who resigned his chancellorship, and John Fisher, bishop of Rochester, refused to sign the acts and were executed. Europe was shocked but Henry was determined to have his way regardless of the cost. Between 1536 and 1541, Parliament at Henry’s behest, dissolved England’s monasteries and nunneries. It is important to understand that there were numerous religious houses in England that owned large tracts of land worked by tenants. When Henry dissolved them, he transferred a fifth of England's landed wealth to new hands. This was a calculated move on Henry’s part designed to create landed gentry beholden to the crown. Henry’s personal life was a disaster at best. Anne Boleyn produced only one child, Elizabeth. Anne soon lost favor with Henry who had charges of adultery and treason trumped up against her; and finally had her executed in 1536. Both Elizabeth and Mary, her half-sister by Catherine of Aragon, were both declared illegitimate although Henry saw that they were well cared for. Henry then married Jane Seymour, who finally gave Henry a son, Edward, but she sadly died shortly after from the effects of the childbirth. Henry then married Anne of Cleaves on the advice of Thomas Cromwell, who hoped to create a marriage alliance with a Protestant German prince. Henry was not pleased with Anne; the alliance was dropped; Anne agreed to a quick annulment and Cromwell was beheaded. Henry next married Catherine Howard, half his age, but she did commit adultery and was beheaded in 1542. Henry’s last wife was Catherine Parr, a well-educated widow and patron of humanists and reformers, who was Henry’s nursemaid until he died. Henry broke from Rome but he was in most aspects religiously conservative. He did allow English Bibles to be placed in English churches; moreover in his Ten Articles of 1536, he made only mild concessions to the Protestant thinking reformers in England. The Articles stressed the Bible and the Creeds; the real presence in the Eucharist, the sacrament of penance, the use of images and pictures; the invocation and honoring of saints; purgatory and prayers for the dead; and the traditional rites and ceremonies of the Church. However, in a major concession, the Articles did stress Justification by Faith, joined with charity. Henry also, despite his own hypocritical liaisons and adulteries, threatened to execute any clergyman who was caught twice in concubinage (living with a woman as her husband). Even Archbishop Cranmer had to keep his own wife hidden from Henry. Nevertheless, Protestant ideas continued to spread and drew Henry’s anger. Henry intended to be head of the Catholic Church in England, not a reformed church. So three years later, Henry issued the Six Articles of 1539, which reaffirmed transubstantiation, Holy Communion in the bread only, clerical celibacy and the continuance of private masses and confessions. Protestants angrily called the Six Articles a “whip with six stings.” About all the reformers got was the Bible in English (Tyndale’s New Testament which grew into the Cloverdale Bible of 1535 and finally the Great Bible of 1539) and slight concessions like Justification by Faith. The reformers would have to wait, but not for long. The Reformation would come to England with Henry’s death in 1547. 10 | P a g e When Henry died, he was succeeded by his ten year old son, Edward VI, who was a morose [sad] and sickly child, tutored by Calvinist reformers. During his reign, England was governed by a Regency Council, which was led by his uncle Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, (1547–1549), and then by John Dudley, 1st Earl of Warwick, (1550–1553), who later became Duke of Northumberland. Edward and his regents were deeply committed Calvinists and corresponded with John Calvin. Henry’s Six Articles were repealed and both clerical marriage and communion in both kinds were legalized. The Reformation had now come to England; not political like Henry’s but religious. In 1547, the Chantries (places where Masses for the dead were offered) were dissolved. In 1549, the Act of Uniformity imposed the Book of Common Prayer on all English churches. It was a conservative revision of the old Latin Mass - simplified and translated into English. In 1550, images were ordered to be removed from churches and altars replaced with Communion Tables. After Charles V’s victory at Mühlberg many Protestants fled to England, among them Martin Bucer, a reformer of both Lutheran and Calvinist traditions, who assisted the pushing forward of a Protestant agenda. A Second Act of Uniformity was passed in 1552 and imposed a more reformed Book of Common Prayer on the English Church. It contained Forty-Two Articles, written by Archbishop Cranmer, which set forth a moderate Protestant position. The Articles included Justification by Faith, a denial of Transubstantiation (but not the real presence,) and recognized only the Sacraments of the Lord’s Supper and Baptism. But all these changes were short lived because Edward died at the age of seventeen in 1553 and, after some intrigue, Catherine of Aragon’s daughter came to the throne as Mary I. Mary was steadfastly Roman Catholic and determined to reverse the Reformation in England. She has been unfairly given the name Bloody Mary because she dealt so harshly with the reformers. Some indeed were burned at the stake including Archbishop Cranmer but compared to her father and his longer reign, relatively few people died under Mary’s persecutions. Mary married the son of Charles V, Philip II of Spain, and made him king of England. The English hated Philip and never accepted him. When Mary died in 1558, her half-sister, the daughter of Anne Boleyn, came to the throne as Elizabeth I. It would be Elizabeth who would strike a middle course for the English Church known as the Via Media. The Counter Reformation The Roman Church was unprepared for the hammer blows of the Reformation. Nevertheless, it must be understood that there were loyal Roman Catholics, who were eager for reform and only too willing to help the Church and – at the same time - beat back the Protestant threat. The Councils of Constance and Basel had both stripped the popes of much of their secular power but the popes continued to delay real reform. To this end, many new religious orders were founded to push reform from within. The Theatines were a Roman Catholic religious order, founded in 1524 by Saint Cajetan, to groom reform-minded leaders at the higher levels of the church hierarchy. One of the co-founders was Gian Carafa, who became Pope Paul IV (r. 1555-1559). The Capuchin Order arose in 1520 when Matteo da Bascio, a Franciscan friar [monk] in Italy, sought to return the Franciscans to the primitive and holy ways of St. Francis of Assisi. The Capuchins became immensely popular with ordinary people to whom they directed most of their efforts. The Somaschi Order, founded in Italy in 1534 by Saint Jerome Emiliani (and named after the mother-house at Somasca), their goal was to dedicate themselves to the giving of aid and caring for the poor, to orphans, abandoned youths and the sick. The Barnabites, or the Clerics Regular of St. Paul, were founded in 1530 by three Italian noblemen, who vowed to seek no personal gain in their ministry and to give themselves entirely to teaching, hearing confessions, establishing missions, educating youth and ministering in hospitals, prisons and to the dying. It is important to understand that both the Capuchins and the Barnabites successfully repaired much of the moral, spiritual and physical damage done to the ordinary people of war torn Italy. 11 | P a g e In 1535, the Ursulines (Ursuline Order) was founded for women in Italy and France to give religious education to girls of all social classes. The Oratorians was society of priests and lay-brothers who lived together in a community bound together with no formal vows but only with the bond of charity. Founded by St. Philip Neri, they were an elite group who devoted themselves to the promotion of religious literature and church music. Among their members was Giovanni Perluigi da Palestrina, a composer of sacred music who had a profound influence on the development of church music, especially Renaissance polyphony. In addition to these movements, there were the Spanish mystics, Saint Theresa of Avilla (1515-1582), a Carmelite nun who wrote about personal prayer, and Saint John of the Cross (1542-1591), a Carmelite monk, whose most famous literary work, Dark Night of the Soul, tells the story of a human soul leaving its bodily home to find mystical union with God. The journey is called "The Dark Night", because darkness is symbolic of the hardships and difficulties that the soul meets in trying to detach itself from the false values of the world as it struggles to reach the light of union with the Creator. On a broader scale, the Catholic Church, although staggered by the Reformation, soon regrouped and fought back in two powerful ways: one planned and one accidental. The planned response was when Roman Catholic authorities undertook a massive reform within their own church at the Council of Trent. The accidental or unplanned was the founding of the Society of Jesus or the Jesuit Order, which in scope when far beyond the reforming groups just described. The Council of Trent was an assembly of bishops, cardinals, scholars and other church officials, which met intermittently between 1545 and 1563. As early as 1537, Cardinal Contarini presented a report on abuses in the Roman Curia (most notably fiscal practices and paying for sacraments or holy offices or positions in the hierarchy of the church) to Pope Paul III. It was so incriminating that Paul at first tried to suppress it. He failed and the Protestants used the report to justify their actions. So Paul III was forced to call a general council to deal with the scandals in the church. It is very important to understand that the Council of Trent acknowledged the abuses in the church and took serious steps to reform the church, especially the selling of church offices. They also demanded that bishops to follow stricter rules such as being highly visible by preaching regularly and conducting annual visitations to the parishes in their dioceses. Trent also produced a standardized liturgy (or Mass) and defined Roman Catholic theology in detail, a monumental task that (with some additions) would last for 400 years until the famous Vatican Two Council of the early 1960s. The Council of Trent affirmed traditional Scholastic education for the clergy, the role of good works in salvation, the authority of tradition (i.e., church councils), the seven sacraments, transubstantiation, withholding the consecrated wine from the laity, clerical celibacy, purgatory, prayers for the dead, veneration of the saints, relics and indulgences (not the abuse of indulgences). Finally the council required that all clergy observe strict standards of discipline and morality. Trent also did much to found schools to educate children and decreed that every diocese have at least one seminary to prepare men for the priesthood (i.e., be celibate, neatly dressed, well-educated and visible and active among their parishioners). Trent also offered resistance to Jansenism, a movement within the Catholic Church (mostly in France) that echoed the Augustinian tradition and Calvinism in that it emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. Most kings and princes were suspicious of Trent because they feared a revival of papal power and more outbreaks of religious strife in their domains. Over time, however, the popes and the Catholic Church gained the trust of Catholic rulers who came to understand that Trent was solely about religious reform and not political machinations. 12 | P a g e The Society of Jesus: While the Council of Trent dealt with doctrine and reform, the Society of Jesus went on the offensive and sought to expand Roman Catholic territory and win back Protestants to the Roman Church. The society’s founder was St. Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556), a Basque nobleman and soldier who in 1521 suffered a devastating leg wound that ended his military career. While recuperating he read spiritual works and popular accounts of saints’ lives. His life changed and he resolved to put his energy into religious work. In 1540 he founded a new religious order: the Society of Jesus, or the Jesuits. Loyola’s quintessential work (a work that is the essential embodiment, criteria or yardstick of something) was Spiritual Exercises, (composed from 1522-1524) which are a set of Christian meditations, prayers and mental exercises, divided into four thematic 'weeks' of variable length, designed to be carried out over a period of 28 to 30 days. They are a perceptive psychological guide to develop self-mastery over one’s feelings in order to live a Christian life. The manual, written for Catholics of the sixteenth century, is popular among many non Roman Catholics today. The Jesuits required its members to complete a rigorous, advanced education in theology, languages (classical and modern), philosophy, literature, history and science. As a result of this preparation – and their unswerving loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church – they made incredibly effective missionaries. They were able to out-debate and/or out-argue most of their critics. They served as advisors to kings and princes. The Jesuits won back some Protestants especially in Germany and Austria, but were most successful as missionaries in India, China, Japan, the Philippines, and the Americas, making the Roman Catholic Church to this day the largest and most global Christian religion. The Social Significance of the Reformation There is an anecdotal story in The Thorn Birds, novel by Colleen McCullough, in which a priest in the early twentieth century is discussing the Reformation with his bishop. The priest makes some unflattering remarks about the Protestant reformers and is surprised when his bishop said: that may be true but never forget that the Reformation gave us a better mannered Catholic Church. In the fifteenth century (1400s), there was much to be desired concerning the “manners” of the church. The clergy and religious made up six to eight percent of the population; they were everywhere and had considerable authority which they often abused. They legislated and taxed, they had their own law courts and, when they did not get their own way, they used blackmail devices such as excommunication, or other forms of religious censure in order to deprive, suspend or limit membership in the church, including admittance to heaven. As the Sixteenth Century opened, the church still pervaded every aspect of life. The church calendar regulated daily living and about one-third of the year was given over to some kind of religious observance or celebration. Periods of fasting, when certain foods like meat, eggs and butter were forbidden, were mandatory (remember 1522, when Zwingli broke the Lenten fast because it was not Biblical). Monasteries and nunneries were prominent and powerful institutions. They educated the children of the nobility and were well paid for their services. On the streets of all towns and cities, friars (like the Franciscans) begged for money. The mass and other church services (except for sermons) were in Latin. Images of the saints were venerated almost to the point of idolatry and religious shrines made huge amounts of dollars from pilgrims who would travel for months to reach such shrines; and then pray and give an offering, hoping for a miracle or eternal salvation. And, of course, special preachers, like John Tetzel, would come and sell indulgences. Many clergy visited prostitutes or kept concubines and all the clergy were exempt from taxation and from criminal codes. It is no wonder that society in general was open to the teachings of the reformers. 13 | P a g e By the mid Sixteenth Century however, after the Reformation had become a reality, there were visible and permanent societal and religious changes. Even though the same aristocratic families governed as before and the rich generally got richer as the poor got poorer, the number of clergy fell by two-thirds and religious holy days shrank by one-third. In northern Europe, monasteries almost disappeared in non-Catholic areas; in France and southern Europe, there was a smaller drop in the numbers of clergy and monasteries were better governed - as the new orders like the Capuchins and Ursulines brought a more authentic Christian charity to ordinary people. In all Europe, the number of churches dropped by a third; the Protestants worshiping in the vernacular and the Catholics in Latin. Catholic churches remained ornate with pictures, stained glass, altars and shrines with relics but many Protestant churches removed most of these - with Calvinists worshiping in plain white-washed chapels. In Germany, copies of Luther’s translation of the Bible (or excerpts of it) were found more and more often in private homes and Protestant clergy urged the reading and meditation of the Bible. In England, the reforming clergy under Edward VI encouraged the reading of the Great Bible in all churches and even his sister Mary, when she succeeded him, continued the practice. Calvin encouraged personal study of the Bible and compared the Bible to a pair of glasses, that enable humans to properly interpret what they see in creation: For as the aged, or those whose sight is defective, when any book, however fair, is set before them, though they perceive that there is something written, are scarcely able to make out two consecutive words, but, when aided by glasses, begin to read distinctly, so Scripture [in the same way], gathering together the impressions of Deity, which, till then, lay confused in our minds, dissipates the darkness, and shows us the true God clearly. Protestant clergy were encouraged to marry; Catholic clergy were required to remain celibate. Clergy now paid taxes and were punished for their crimes in secular courts. In Protestant communities, roughly equal numbers of clergy and laity helped govern the community but in Catholic countries the Church worked with the state in governing the community. Not all Protestant clergy and laity remained enthusiastic about the new religion and over half of the original converts (partly due to the work of the Jesuits) returned to the Catholic Church by the end of the sixteenth century. In the mid sixteenth century one-half of Europe was Protestant; a century later the percentage was one-fifth. Education The Catholic theologians of the Counter Reformation recognized the connection between humanism and the Reformation. They saw the dangers of humanism and the damage humanism without proper guidance had done to the church, so they tempered humanism with the guidance of the Scholastic Fathers of the high middle ages, such as Thomas Aquinas and Peter Lombard. In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius Loyola argued that the Scholastic fathers - being of more recent date - had the clearest understanding of what the Bible and the Church fathers taught. Thus the Scholastics should be used as a lens to study the past. But this was not so in northern humanism. One of the major cultural achievements of the Reformation was the introduction and implementation of humanist educational reforms in new Protestant schools and universities. Moreover, the northern humanists were better able to maintain a balance between the humanities and religion and were united in their opposition to medieval Scholasticism which – it should be remembered - was not so much a philosophy or a theology as much as a method of learning. Scholasticism placed a strong emphasis on dialectical reasoning which was often a dialogue between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject, both of whom wish to establish the truth of the matter by dialogue and with reasoned arguments. Protestant Humanists broke free of dialectical reasoning by philological accuracy and an objective quest for truth (remember Lorenzo Valla and his uncovering the Donation of Constantine forgery) in the investigation of original sources which proved to be a powerful tool for the exposition of Protestant doctrines. 14 | P a g e In 1518, when Philip Melanchthon, a humanist professor of Greek, arrived at the University of Wittenberg, his first act was to reform the curriculum on the humanist model. In his first address, On Improving the Studies of the Youth, he claimed to be the defender of good letters and classical studies against the barbarians who still practiced the barbarous arts. By barbarians, he was referring to the Scholastics, whose methodology of dialectical reasoning to find truth, he believed actually hurt both good letters and sound biblical doctrine. Melanchthon considered Scholasticism as a mortal hindrance to Greek studies, mathematics, Biblical studies and oratory and he urged more careful study of history, poetry and other humanistic studies. Luther and Melanchthon completely restructured the university curriculum. Commentaries on Peter Lombard, Scholastic lectures of Aristotle and canon law were dropped. Students read primary sources instead of scholastic commentaries. Candidates for theological degrees had to defend themselves on the basis of their own studies of the Bible. Finally, new chairs of Greek and Hebrew were created. John Calvin and his successor, Theodore Beza, founded a Genevan Academy (later the University of Geneva) to train Calvinist ministers and pursue ideals similar to those of Melanchthon and Luther’s University at Wittenberg. Calvinist refugees who studied at Geneva would later carry Calvin’s ideas to France, Scotland, England and the New World. There was also the side benefit of spreading Hebrew and Greek studies to other European countries. Not all northern humanists agreed. Erasmus came to fear the Reformation as a threat not just to the Roman Catholic Church but to the liberal arts and sound learning. Sebastian Franck (1499-1543), a German freethinker, humanist, and radical reformer, pointed out the parallels between Luther’s and Zwingli’s debates over Christ’s presence in the Eucharist to the old Scholastic debates about the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The bottom line was that both Erasmus and the free-thinking Franck saw a narrowing of humanism once it was taken over by Protestant thinking. Sociologically, two observations can be made. First, The Reformers were politically conservative and sought to work within the political framework they knew. They saw themselves as subject to civic responsibilities and obligations. Some scholars believe they were so conservative that they actually encouraged the medieval status quo. Second, Humanist culture and learning remained indebted to the Reformation. Protestant schools preserved for the modern world many of the basic pedagogical achievements of humanism. There, the Studia Humanitatis found a permanent home even at the height of conservative Protestant Reformation. The Changing Role of Women and Family Life The Reformation challenged the traditional way of looking at women. Women were now seen as wives and helpmates, not temptresses whose only virtue was to be life-long holy virgins. Thus the reformers encouraged clerical marriage and praised women for their vocation as wives, mothers and some professions such as midwifery and working beside their husbands as shopkeepers or merchants. Wives did, to be sure, remained subject to their husbands but new laws gave them greater dignity and protection. Clerical marriage was praised not just to relieve the male from the temptation of fornication but because the partnership of husband and wife in marriage actually assisted the minister to be more effective by understanding married life and by the wife’s helping her husband with the cares of daily living. Thus by rejecting the medieval ideal of celibacy, the Protestants stressed, perhaps for the first time since the early days of Christianity, the sacredness of home and family. In Protestant countries, women slowly began to achieve a growing equality with men which was reflected when women were openly allowed more and more to seek divorce, especially on grounds of adultery and abandonment. 15 | P a g e This led to the idea that marriage was not just for the procreation of children or to remove the temptation to fornication but was an institution of mutual support. As written in Cranmer’s 1549 Book of Common Prayer, matrimony was ordained…for the mutual society, help, and comfort, that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and adversity. In Protestant countries women gained the same rights as men to divorce and remarry and more grounds for divorce and remarriage were enumerated. Now that the Bible was read in the vernacular, women found new dignity based on the Scriptures. For example in Book of Ephesians, it does indeed say that a woman must obey and reverence her husband but then a few lines later it also says that a man must cherish his wife and love her as Christ loved the Church ending with the words: Nevertheless let every one of you in particular so love his wife even as himself; and the wife [see] that she reverence [her] husband. Convents (nunneries) were often attacked by unhappy nuns who criticized the male dominance over them, as only males could be priests or bishops and only males could celebrate the Eucharist or administer the sacraments. On the other hand, some nuns of noble extraction opposed such changes, arguing that the convent offered them a more independent form of life because it kept out the secular world. Noble and upper class women, who had found new freedoms during the Renaissance, also found grounds for lives more independent of male supervision. Like the Ursulines, Protestants wanted women to become pious housewives and so they encouraged the education of girls so that they could model their lives on the Bible. All in all, in Catholic and Protestant countries alike, women did make many advancements in dignity and personal freedom even though these new rights paled to the rights many women take for granted today. Later Marriages Between 1500 and 1800, European men and women married at later ages than they had during the middle ages: men in the mid to late twenties and women in their early to mid-twenties. Catholic and Protestant countries both required mutual (and if applicable for young adults, parental) consent, and public ceremonies before marriage could be deemed valid. Late marriages reflected the difficulties couples had in supporting themselves. So marriages were delayed. Moreover, in the sixteenth century, one in five women never married and combined with a large number of widows (from religious wars) created a problem of an excess of marriageable females. Later marriages also created shorter marriages and higher female mortality rates during childbirth. Thus, late marriage also meant frequent remarriages for men; and so it comes as no surprise that between 1600 and 1800 the number of orphanages and Foundling Homes or Hospitals (places where unwanted infants were left and raised) grew dramatically. Arranged Marriages Marriages tended to be arranged and parents met and discussed the terms of marriage before the betrothals and marriage took place; and wealth and social standing were important factors. Yet unlike previous ages it was not uncommon for brides and grooms to have known each other for some time before marriage and parents were becoming more sensitive to the bride and groom’s feelings toward one another. Parents rarely forced strangers to live together and children had more influence on a potentially undesirable marriage, which was in itself (even by the old rules often ignored) was an impediment. So the standard became that the best marriages resulted when both the bride and the groom and their families agreed on the choice marriage partners. Family Size Families usually consisted of a father and mother (and perhaps one or more of their parents) with anywhere from four to eight surviving children. Most families had at least five children but child mortality rates were high with one child in five dying by the age of five and only half of families’ children reaching the age of twenty. 16 | P a g e Wet Nursing and Birth Control Wet Nursing was the practice of women who were paid to nurse other women’s’ children. Although frowned upon by many Churches, wet nursing made it possible for many poorer women to supplement family income. Having poorer women as wet nurses appealed to many upper class women – and was like what we might call a status symbol. However, wet nursing seems to have increased infant mortality to milk other than that of their own mother, especially when wet nurses often were malnourished and lived in less sanitary conditions. On the other hand, new mothers who nursed found it to be a natural form of Birth Control – about 75% effective. All artificial methods of birth control (dating back to antiquity and mostly ineffective) were more common than usually assumed and only partially effective. Nevertheless, all of these were considered a major sin by Church officials who referenced Thomas Aquinas who had taught that a moral act must aid and abet, never frustrate, nature’s goal. So the question was often hotly debated whether or not sex was to be used just for procreation or for mutual affection (enjoyment) and support as well. Loving Families In our culture today, love between spouses and between parents and children is a given. But in the Renaissance and Reformation of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, such as not a given. Children between the ages of eight and thirteen we often sent from their homes to become apprentices, in study in schools or even become employees – and often in unhappy circumstances or surroundings. Widowers and widows often remarried quickly – often within a few months – of losing a spouse and there were many marriages of extreme differences of age such as men in their fifties married to girls in their late teens or twenties. The reason for such seeming callous attitudes towards love and parental affection is rooted in pragmatism (practicality). Children taught a trade became self-supporting. Life was hard and at best uncertain, so quick remarriage was natural. A young bride married to an older man would generally not suffer from hunger or want. It is an error to misjudge the apparent coldness or over practicality of men and women who lived in a world in which disease, famine or war could and did destroy lives. The Reformation and Literature In the last chapter we saw how Humanism affected the values of European Literature. During the Italian Renaissance, the human person and his or her needs and personality broke forth. In his poem Il Canzoniere, Petrarch is captured by romantic love for Laura whose beauty made his give up his priestly vocation. And Boccaccio’s Decameron depicted bawdy sketches of love, witticism and practical jokes. Baldassare Castiglione in his Book of the Courtier described the ideal princely court, the duties of a courtier and many details about the philosophical, cultured and lively conversations that should take place among courtiers. Christine de Pizan chronicled of the great women of history. And in his book The Prince, Machiavelli gave secular rulers advice on how to gain and hold on to power. In the Northern Renaissance which was admittedly more serious and religious in feeling, Jean Bodin in his treatise, The Six Lives of the Republic, defended the sovereign rights of a monarch. Erasmus was the literary giant of the Northern Renaissance. We have noted his Colloquies or dialogues teaching his students how to speak and live well; his Adages (Leave no stone unturned and Where there is smoke, there is fire); The Praise of Folly, his satirical examination of pious but superstitious abuses of Catholic doctrine, and, of course, his satire Julius Exclusus, picturing the worldly Pope Julius II left outside the gates of Heaven. Finally, there was the English humanist, Thomas More, whose best known work, Utopia, depicted an imaginary society that had overcome all social and political injustice by holding all property and goods in common and requiring every person to earn their own living. 17 | P a g e The Reformation continued these changes and the writers of the post-Reformational period had elements of both humanism (man is the measure of all things) and intense religious reform (man is saved by Faith alone). Spanish post-Reformational literature was found in two major influences: traditional Catholic teaching and the aggressive piety of the Spanish monarchs. Thus Spanish literature remained more Catholic and medieval than French or English literature where two major Protestant movements had affected the culture. Spanish writers who best reflected this conservatism were priests: Lope de Vega and Pedro Calderon. But one Spanish writer, considered to be Europe’s first novelist, was able to blend medieval piety and humanism; he was Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. Cervantes (1547-1616) was born in Alcalá de Henares, in Castile, the son of a barber-surgeon of Galician descent and daughter of a noblewoman whose father had lost his fortune. As a child he moved about a lot and how much education he received is debatable. As a young man, he worked for a Spanish cardinal in Rome and later, as a naval-marine, he was decorated for gallantry in the naval Battle of Lepanto (1571) against the Turks. His ship was later captured and he spent five years as a galley slave until ransomed by his parents. Back home, he worked as a tax collector and was imprisoned several times for padding (cheating at) his accounts. And it was around 1603, while in prison, that he began his most famous work, Don Quixote. Don Quixote follows the adventures of Alonso Quijano, a minor nobleman, who reads so many novels of chivalry that he decides to set out as a wandering knight in search of adventure, under the name Don Quixote. He puts on rusty old armor with a barbers basin for a helmet and recruits a simple farmer, Sancho Panza, as his squire, who often uses wit in dealing with Don Quixote's exaggerated speeches on antiquated knighthood. He chooses for his inspiration a simple peasant girl named Dulcinea whom he imagines to be a noble lady to whom he could dedicate his life. Sancho watches with amusement as Don Quixote does “battle” with a windmill which he supposes is a dragon and then proceeds on a series of more misadventures each time making a fool of himself. His adventure ends sadly when a friend defeats him and forces him to renounce his quest for knighthood. The tragedy is that Quixote does not return to his senses but returns to his village to die a brokenhearted old man. Don Quixote with its juxtaposition of down-to-earth realism and religious idealism is important because it is the classic model of the modern romance or novel, and the prototype of the comic novel. Just as Cervantes left his indelible mark on the Spanish language and literature, so in like manner, William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) has come to be regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. We know that he was brought up at Stratford-uponAvon and married Anne Hathaway at the age of eighteen fathering three children. We know that he was a schoolteacher and as such gained a broad knowledge of Renaissance literature. By 1592, he was part owner of a playing company. He produced most of his known work between 1589 and 1613. His early plays were mainly comedies and histories, genres he raised to the peak of sophistication and artistry by the end of the 16th century. He then wrote mainly tragedies until about 1608, including Hamlet, King Lear, Othello, and Macbeth, considered some of the finest works in the English language. In his last year, he wrote tragicomedies and collaborated with other playwrights. Shakespeare was interested in politics but expressed no radical puritan or political opinions. He assessed government through the lens of the person (usually a ruler) who was the focus of his study. He was politically conservative and accepted the political, religious and social structure of his day. He was Anglican and expressed no support for Puritans or Roman Catholics. In Shakespeare's day, English grammar, spelling and pronunciation were less standardized than today and so his powerful expression helped shape our modern language. Although Shakespeare was not greatly revered in his lifetime, he nevertheless received a large amount of praise and recognition. His greater importance lay in his ability to express universal human themes as did the great dramatists of Ancient Greece. 18 | P a g e