Chile (1929-1940). “Archivo Nacional. Interior.”

advertisement

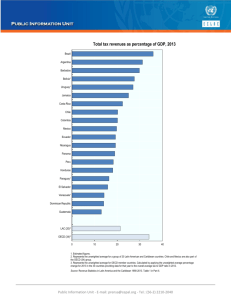

1 1 Simposio: El desarrollo histórico de las economías latinoamericanas en perspectiva comparada Coordinadores: Luis Bértola y Gabriel Porcile LURCHING TOWARD MODERNITY: CHILE AND MEXICO, ECONOMIES AND STATES, FROM THE GREAT DEPRESSION THROUGH THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1924-1945 Michael Monteón History Department University of California, San Diego mmonteon@ucsd.edu (fax 619-534-7283) In general, Latin Americanists rarely look at two nations in the same period and to discuss, in some detail, different responses to a common set of circumstances. Specific comparisons of Chile and Mexico are rare. A title search through the massive University of California computerized library yielded fewer than 100 titles that included Chile and Mexico and only one that focused on those two countries.(Askari 1991) The events of the Great Depression and the early 1940s, however, allow us to be very specific and, hopefully, more precise about why and how governments and economies evolved in response to global change. The Depression and the onset of the Second World War ripped through every Latin American nation, altering two fundamental characteristics in the region. Since the late nineteenth century, most of Latin America had embarked on a pattern of export-led progress and had rationalized its goals in the prevailing rhetoric of economic liberalism. In each country, the collapse of export prices between 1925 and 1932 brought severe crises to important, often crucial, economic sectors. In each, too, economic liberalism, already on the defensive in the aftermath of World War One, suffered a reversal. Even those who claimed to believe in a market economy tied their expectations to greater governmental intervention.(Cortés Conde and Stein 1977; Maddison 1985; Thorp 1992; Bulmer-Thomas 1994) Historians of the period usually use 1930 as a dividing point between the era of export economies and that of "growth from within," when one nation after another ignored liberal economic theory and emphasized the protection of industry and industrial growth as the principal stimuli to employment and progress. Chile and Mexico reflect these changes. In each nation, the depression leads to a more centralized government with broader economic powers. In each, there is a political mobilization of business associations, professional guilds, labor unions, and, in the case of Mexico, peasant leagues as well. In each, the origins of these mobilizations are in the export era. Historians of Chile have often ascribed these changes to the depression, but the historiography of Mexico is I am deeply indebted to Guillermo Guajardo for the careful reading he gave an earlier version of this paper. He is also the only other specialist I know who is comparing Chile’s history to Mexico. 2 2 different. With the exception of John Womack, Jr.'s essay on the Mexican economy, more than twenty years ago, an obscure essay by Arnaldo Córdova and the more recent work of Enrique Cárdenas and Stephen Haber, the changes of the 1930s in Mexico are usually described as the outcome of the Mexican Revolution that began in 1910.(Womack Jr. 1978 Winter; Córdova 1981; Cárdenas 1987; Haber 1989; Cárdenas 1994; Córdova 1995) While no one can ignore the importance of the Revolution in Mexico, it is important to explore the reorganization of the Mexican state in the 1930s and early 40s in relation to the rest of Latin America. Nonrevolutionary factors may be central to Mexico's evolution. Or, we may find that despite the Revolution, factors external to both Mexico and Chile were driving the basic political evolution of both countries. Let me consider four elements common to both nations. The first is the general economic trends in response to the Great Depression. The second was the need to reconfigure the state, especially the relation of political parties to the government. And the third, which can only be suggested here, is the rise of populist sentiment. Laborers in both nations and, in Mexico, peasants as well, become part of the "nation," which must be organized by political leaders if they are to maintain office. Finally, the Second World War is the moment that crystallizes possibilities. We can say that, in each country, the class and party characteristics that exist in 1945 remain central to the political economy for the next three decades. We know at the outset that these common elements have very different political outcomes. Chile witnesses the revival of a multi-party system and a centralized government, dominated by the presidency, but beset by problems of underdevelopment that explode in the brief era of Salvador Allende's socialist experiments and the military coup of 1973. The story of Mexico is the formation of single-party state run by civilians. The party, which takes its final name as the PRI [Partido Revolucionario Institucional or Institutional Revolutionary Party] in 1946, has authoritarian qualities but permits public discussion. It demonstrates a remarkable ability to recast itself in new images, change its economic policies, and continue dominating the political economy.(Heise González 1974; Meyer, Krauze et al. 1977; Meyer 1978; Monteón 1982; González Casanova 1983-1986; Loveman 1988; Camín and Meyer 1989; Ruiz 1992; Monteón 1998) Mexico is as great an exception to Latin American generalizations in the twentieth century as socialist Cuba. I cannot explain this exceptionalism but I do find that, in comparing Chile and Mexico, some of the standard hypotheses for each nation do not seem to bear very close scrutiny 1. Some Broad Generalizations In many respects, Chile and Mexico seem too different in their make-up and histories to bear much comparison at all. Mexico is more than two and half times the size of Chile; in the 1930s, it had 16.5 million people and Chile only 4.2 million. Mexico has had a different state administration since the early nineteenth century, and its leaders have faced the problem of building a nation out of disparate societies with large Indian populations. Ethnic differences in Chile are not as pronounced or involve as large a Native American population. What is more, in 3 3 the 1930s, much more of Chile's population lived in "cities" (larger than 2,500 residents) than Mexico's: 49.5 per cent as opposed to 33 per cent. During the 1920s, events in Latin America, as elsewhere in the Atlantic economy, reflect the disorientation and financial problems caused by the world war, problems that led directly to the stock market crash of 1929 and the banking collapse of 1930-1933. Disillusionment with democratic rhetoric was accompanied by desperate measures to revive market economies. Mexico became dependent on the United States prior to the Revolution; Chile switched from relying on Great Britain to a dependence on the United States during the First World War. In the 1920s, this dependence -- despite the impact of the Mexican Revolution -- increased in both nations.(Cardoso 1980, p271; Monteón 1982, chap. 5; Albert 1988, p307-309) U.S. investment in each country by the end of the 20s was about 700 million dollars, and most of it was in mining or oil.(Rippy 1958, p43) Thus, one of the factors that would influence the political stability of each country was the behavior of the U.S. government in response to pressures from U.S. corporations that had invested in that country.(Meyer, Krauze et al. 1977,chap. 1; Hall 1995,p142) The 1920s provide us with some crucial similarities in each nation. In each, the political leadership must contend with the breakdown of an export-oriented liberalism. The course of the breakdown is different, of course, but the fact that forms of political organization that had maintained basic stability since the 1880s in the case of Mexico and since 1891 in Chile no longer worked in 1925 bears some discussion. Whether we wish to call this the end of oligarchical liberalism or tag it with some other label is less important than how political leaders in the 1920s envisioned a new state. What was their project? We know that it was not democracy. Still, rulers in each nation wanted elections to legitimize holding office. Both nations faced the prospect of mass politics, and in each country, those who held political office were determined that this should not lead to popular sovereignty. The initial project was to share office with portions of the middle class -- mostly lawyers, school teachers, and some labor leaders -- and to claim that such a reapportionment meant the government now represented everyone. The engineers of this effort in Chile were Arturo Alessandri, a reforming Liberal, and Carlos Ibáñez del Campo, once a cavalry officer. The two, through a series of dramatic events, grew to fear and hate each other. In Mexico, the project was launched by the victors of the Revolution, particularly, Generals Alvaro Obregón and Plutarco Elías Calles.(Meyer, Krauze et al. 1977,chap.1; Meyer 1986) Each project required, in each nation, the use of armed force. Alessandri, Ibáñez, Obregón and Calles shared not only an appetite for office but an exploration of new political coalitions. They were not above experimentation, often used rhetoric that threatened the economically privileged, and were actively seeking models of political organization for a new state. All of them called themselves revolutionaries, none called Census data for both nations. 4 4 himself a "corporatist," but that is how we would label them.(Pike and Stritch 1974; de Sousa 1978; Wiarda 1981; Lehmbruch and Schmitter 1982; Williamson 1985; Morales-Gomez and Torres 1990; Wiarda and Klein 1996; Wiarda 1997) Each wanted a more centralized form of government, relating administrative organization and policy to specific economic sectors, and based on hierarchical relations between public and private interests and the rich and the general population. Each rejected the consequences of unbridled capitalism by which he meant the problems of mass poverty, illiteracy, and the threat of social revolution; none, however, rejected a market economy. Each attempted an alliance with urban labor, either by coopting the labor organizations that existed or by instituting new ones that could be regulated by the government. Thus, in ways that must have made all of them uncomfortable, each flirted with populism -calling up the politics of redistribution -- while trying to avoid antagonizing capital, foreign and domestic. Anyone looking at Chile and Mexico in the late 1920s would have bet that it was Chile that would be the more stable and prosperous of the two nations. President Arturo Alessandri's administration had failed to achieve his reformist program and the military had moved in after a coup in 1924. But by 1927, Chile's economy was recovering and Carlos Ibáñez was very much in charge and well-liked by foreign and domestic business interests. By contrast, Mexico was still obviously recovering from revolution and had plunged into a religious civil war.(Meyer 1974; Ruiz 1992,p339-385) Hindsight argues that, nonetheless, it was Mexico that generated the more dynamic and successful political organizations. It used to be argued that Mexico also had the more successful economy. The scholarly literature on Chile's political economy in this period emphasizes disorganization and a stagnating or slow-growing economy. That on Mexico stresses the origins of the "miracle," the striking growth of industry and rapid economic expansion that accompanied the onset of World War II and continued into the 1950s and 60s.(Mamalakis and Reynold 1965; Reynolds 1970; Ffrench-Davis 1973; Mamalakis 1976; Cárdenas 1987) Economic success can obviously stabilize political support and continuity. But was Mexico before 1940 or even 1950 that much more successful than Chile? I do not think so. In an admittedly gross approximation, I looked at the pattern of growth in the gross domestic product of each country from 1925 until the late 1940s. In Appendix I.1 and I.2, I turned these figures into indices based on 1925-1927 to avoid the distortions created by events in 1929 and the crash of the depression. The results are quite interesting. By these estimates, Chile recovers from the crash faster than Mexico and remains somewhat more successful economically thereafter; the contrast is even more surprising when population growth is taken into consideration: Chile's GDP per capita in 1935 is 104 while Mexico's is 87; in 1940, 114 to Mexico's 96; and in 1948, 135 to Mexico's 117. One might argue that this is a misleading indicator, that particular sectors are more important in generating a successful political economy than the overall GDP. As Appendices II.1 and II.2 demonstrate, however, up until 1940, Mexico was not a more industrialized nation than 5 5 Chile; the sharpest contrast in the distribution of economic activities was that, until then, mining and petroleum played a larger role in Chile than in Mexico and that the Chilean government represented a much greater share of the total GDP: ranging from around 9 to 20 per cent in these years, while the Mexican government was only five or six per cent of the economy. This seems to me a key point, and I will return to it later. There is also another element of the numbers that is misleading, and this too, is worth revisiting. The numbers may hide the depths of the Crash, by most accounts the slide from 1929-1932 was much sharper in Chile than in Mexico; the sectors hit in Chile, mining and government spending, had an impact on employment and hunger that exceeded the decline of various sectors in Mexico. The Crash hit Chilean society harder than that of Mexico, but my point here is that its impact on Mexico has been understated. (An exception is, (Cárdenas 1994)) But first, it is necessary to make one observation that struck me as I assembled these numbers. In almost every study of politics and economics that I have read on either country, great weight is given to a handful of sectors: agriculture, mining, industry, construction and government. But as the percentages illustrate in Appendices II.1 and II.2, these sectors combined accounted for no more than about two thirds of the economy of Chile until 1940 and only a little more than half of it thereafter. They make up, in many years, less than half of the economy of Mexico. Have we, in all these studies, been basing our explanations on totally inadequate assumptions? Changes in a third to half an economy can cause no end of political instability. And what are we to make of the internal dynamics of these economies? To my astonishment, well into the 1930s, Chilean agriculture expanded more rapidly than Mexico's; mining and/or petroleum as well as construction in Chile recovered relatively better than Mexico's. (See Appendices III and III.2) By some indices -- compare III.2 and III.4 -- the decisive expansion of Mexico appears only in the late 1940s. Yet, there is no doubt, that by that date the hegemony of the official ruling party was well established while Chile's perennial shuffle of cabinets and political coalitions was beginning to undo the capacity of any government to act with authority. I would suggest one other modification, that of Andre Gunder Frank and others who view the depression as a chance for greater economic autonomy.(Frank 1967) In the crucial moment of 1929-1932, a significant element in regime survival and, therefore, in the overall development of the political economy was not in breaking ties to the United States but in strengthening them. The United States, despite strong Republican opposition to the "bolsheviks" in Mexico City, improved relations with Mexico in the 1920s, opposed or neutralized Calles' enemies, and permitted the Mexican government to suspend debt payments without retaliation. In Chile, neither Ibáñez nor the governments that followed him were able to articulate a set of policies that simultaneously built support at home and won at least acceptance from the United States. President Alessandri (1932-1938), the most successful of Chile's chief executives during the Depression, was unable to elect a successor. Conservative corporatism was never cemented into the political system. The problem for Chile was accented by the fact that it was a far more tradedependent nation than Mexico.(Thorp 1992,p182) There is ample evidence, in short, that the 6 6 Depression did not constitute a break in the role of the United States in the development of these two countries.(Puig Casauranc 1938,p282ff; Portes Gil 1941,p197-200; Zevada 1971,p64-81; Meyer 1978,p36-46; Medin 1982; Garrido 1991,p68-85; Monteón 1998,chap. 1) Indeed, if there is any ongoing legacy of the crash, it is that Chile's capacity to import remained well below the average in Latin America and much poorer than that of Mexico -- well into the 1940s. (Appendices IV.1.h and i; IV.2.h and i; IV.3.h and i) The constriction on the Chilean economy as a whole involved everything from shortages of fuel to shoddy consumer imports from European nations. The theme of shortages of key imports does not seem an omnipresent in Mexican history. II. The Timing of Institutional Arrangements I assume, for the sake of brevity, that the most important political fact in each nation was the reconfiguration of the state that followed the crash, 1929-1932. We know, to take one facet of this process, that everyone in the 1920s paid close attention to both Mussolini and Stalin. Ibáñez and Calles studied various means of creating a more vertically organized set of institutions that would reach from the elite to the general populace and, in some sense or other, represent the economic and social segments of the country while concentrating authority in a political leader. Each of these figures had to improvise in response to events no one could have foreseen. Both did what they could to placate the United States and major U.S. corporations that operated within their countries. Ibáñez chose to create a more presidential government but not to form a government party. He relied on the expansion of government, based not only on a brief surge in exports, but on massive borrowing from New York and London, to buy public support. The communists and anarchists were banned, and government created labor regulations for a new set of "syndicates" that would represent workers. Non-leftist parties were permitted but were not really the basis of the contest for state power. That took place largely within the executive branch. Calles chose to form a dominant party, originally called the PNR (Partido Nacional Revolucionario). It was a loose knit coalition of his supporters and those of Obregón, who had just been assassinated. In an effort to avoid revolutionary fratricide, Calles took himself out of presidency but became the jefe máximo -- reducing Mexico's next three chief executives to men who served at his will. He had the support not only of a large part of the revolutionary chieftains, but of the newly developing professional army, and a corrupt labor federation. This was the beginning of new institutional consolidation -- a reformulation of party and state that remains to this very day. This does not mean that the party’s internal coalitions did not change; in a fundamental way, its purpose changed. The military was eventually removed. And, under Cárdenas, the president came to dominate the party, turning it into a vehicle of executive.(Garrido 1991,p37-51; Knight 1991; MacLachlan and Beezley 1994, 283-294) There are several elements about both the timing and consequence of these institutional 7 7 changes that are worth mentioning. Ibáñez in many respects is a common figure in twentiethcentury Latin American history, the modernizing caudillo. And like most of them, he failed to make a distinction between governing and mobilizing support. He thought a reformulated presidency could serve as a basis of both functions. Laurence Whitehead notes that the Chilean government was far more developed in its transportation networks and administrative capacity than almost any other Latin American nation.(Whitehead 1994,p20) But such a development, with the growing dependence of the general public on deficit spending, brought a severe price in the Crash itself. Calles did not make this mistake. The party he created contributed significantly to political continuity during the Crash, so that Mexico is one of only two (Venezuela is the other) major Latin American nations to endure the crash of 1929-1932 without a change of executive caused by rebellion or coup. A second element is spending your way to popularity is more expensive and less effective than organizing a dominant party. Ibáñez increased the national government until, by late 1929 and 1930 it was 20 per cent of the GDP; by the time his government collapsed, it made up almost a quarter of the economy. (Appendix II.1.e) If one uses 1928 as the base year, within a year a half, the Chilean index of government spending rose to 136. (Appendix II.2.e) By comparison, the Mexican national government made up only about five per cent of the GDP (Appendix II.2.e), it was actually shrinking in size in the late 1920s. (Appendix III.2.e) A third consideration is that an expensive government, which fell into fiscal crisis, left a mobilized, dependent urban sector behind it that caused political trouble for every subsequent administration in Chile. As the crash swept through the nation and the government cut back its spending, it left behind three distinct urban "armies" of unemployed in Santiago and Valparaiso -- the miners from the north, laborers in public works, and white collar government workers -- who raised hell thereafter. Mexico, which had about the same number of unemployed, does not seem to have had this political concentration of anger in its capital. On Chile, see (Chile 1929; United States 1929-1930) On Mexico, seev(Meyer 1978, chap. 1; Malpica Uribe 1985). In a discussion of public institutions, below, I elaborate the much greater success that Mexico had in controlling its labor forces. This is another factor that helps explain why a shrinking government in Mexico could ride out its contraction. It is one thing to become unpopular, as the Maximato was; another to be overthrown. Beyond the crash, institutional arrangements and economic recovery interacted over this simple fact: Chile lacked political continuity and so faced the revival of instability as a constant prospect in the 1930s, while Mexico was developing greater stability despite intense sources of conflict. Five chief executives followed Ibáñez within a year and half of his removal: two of these came to office by means of national election, the others by actions of the armed forces. This was the highest executive turnover in Chilean history. The Mexican Maximato with its three subservient Presidents gave way to the election and administration of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940). The Cárdenas' sexenio is still the most important populist administration in the nation's history. The core of that mobilization was the creation of new labor and peasant organizations, within the ranks of the official party -- and a renaming of the party, the PRM [Partido Revolucionario Mexicano or Mexican Revolutionary Party] in 1938. From the time of 8 8 the CROM [Confederación Regional Obrero de México or Regional Labor Confederation of Mexico] in 1919, Mexican leaders had been forming pacts with workers in the capital; the CROM and, later, the CGT (Confederación General de Trabajadores or General Confederation of Labor) had each made deals that traded legal recognition in return for not opposing the government. In his administration, Cárdenas instituted the most sweeping land reform that Latin America had ever seen and consolidated peasant loyalty through the CCM (Confederación Campesina Mexicana or Mexican Peasant Confederation).(Clark 1934,p57-69; Barboso Cano 1980,p93-111; Córdova 1980,chap. 1; Carr 1981, 86-193; Tamayo 1987,chap. 2; Zimerman 1991,p42,196,255) The results were uneven, a majority of peasants never received any land. But these twin changes brought labor and peasants within the networks of legitimate lobbyists, albeit abusive networks, with channels through bureaucratic caciquismo that they could use to present their grievances.(Knight 1992,p138) No such set of structures evolved within Chile before 1950. Peasants were excluded, and any time they attempted to organize, they were repressed. Labor organized in the face of government hostility in the 1930s, but it was never part of any set pact – it had no set connections to the executive branch of the government.(Monteón 1998,chap.7-8) Curiously, the most violent state within the most violent society created the greatest degree of political stability. Over and over again, it is clear that Mexico in the late 1920s and in the 1930s is a much more violent set of places than anywhere in Chile. This was not mean that Chile was peaceful or without major tumult – far from it. There were class confrontations throughout the interwar period in which hundreds of ordinary people lost their lives: 1925 Coruña, 1932 Naval Uprising, 1935 at Ranquil, and so on. But this is nothing in comparison to the major bloodlettings of the 1920s in Mexico. The elimination of Mexican revolutionary caudillos in the 20s is a well-known story as is the Cristero rebellion. The first process included two military rebellions, that of de la Huerta in 1923 and of Escobar in 1929. The second led to tens of thousands dead.(Meyer 1974) In the state of Veracruz alone, armed peasants (forming guerrilla bands) fought against white guards of landowners, and occasionally, state forces from 1920 through the late 30s.(Salamini 1978) In addition, the archival materials on regional protest make it clear that confrontations between labor organizers, peasant committees and even common householders with local bosses -- most of them municipal office holders, governors, and/or landowners -- were much nastier than anything I have read occurring in Chile in the same period.(Chile 1929-1940; Salazar 1990) (México 1929-1943) Ibáñez was overthrown in 1931 in the wake of killing two middle class young men during demonstrations in Santiago; Alessandri cost conservatives the election of 1938 when the carabineros slaughtered a few dozen Nacis in the capital. How many thousands died under Calles alone? Violence was a much more effective instrument of local and national political control in Mexico than Chile. Another consideration is the relation of economic expansion and political stability. And here, again, the numbers tell an interesting story; one that is at odds with portion's of the "progressive" mythology in each nation. The standard view of Chile in the 1930s goes something like this: Arturo Alessandri won the presidency in 1932 with a liberal-left electoral coalition, then (for reasons usually 9 9 unexplained except his perfidy), he abandoned the left and socially progressive concerns and realigned his government with the parties of the right, especially the Conservatives and Liberals in Congress. He betrayed his working class supporters, improved the prospects of the rich, and abandoned his populist roots of the 1920s. In 1938, the right ran Alessandri's Finance Minister Gustavo Ross Santa María for the presidency and lost to a center-left Popular Front, led by Pedro Aguirre Cerda. Aguirre Cerda was the working man's great hour in Chile (before the administration of Salvador Allende in the early 1970s), raising real wages and enacting social reforms that had been pending since the 1920s.(Palma Zuñiga 1963; Palma Zuñiga 1967) In fact, both Alessandri and Aguirre Cerda labored under the shadow of the Depression. Alessandri cut back government spending and raised taxes because an inflationary spiral had already begun, and he knew from his presidency in the 1920s how disastrous that could be. His efforts cost him the support of the middle class and labor. Aguirre Cerda engaged in deficit spending and heavy borrowing from the export-import bank; wages went up briefly before inflation created the class cleavages that brought down the Radical presidencies in the late 1940s.(Monteón 1998, chap. 6,8) The Cárdenas' administration presents a different trajectory, albeit over terrain that is much more heavily contested by historians and contemporary politics. But in any reckoning of reputations -- who did most for the working people of his nation? -- it is safe to say that Cárdenas would rank well above either Alessandri or Aguirre Cerda. This is a judgement with which I agree.(González 1979; Hernández Chávez 1979; González 1981; Hamilton 1982; León and Marván 1985; Knight 1994) While government expansion does not equal an improvement in popular welfare, it is at least a clue to how active the government has become. The government under Cárdenas doubled in size, rising on the index from 75 in 1933 to 158 in 1940. (Appendix III.2.e) And this expansion outran the pace of change in GDP per capita, 79 in 1933 and 96 in 1940. (Appendix I.2.d) By comparison, the index of Chilean government spending went from 55 in 1933 to 86 in 1940 -- in short, even as late as 1940 the government was not spending as much as it had in 1928, let alone anything like the sums Ibáñez expended before he fell. (Appendix III.1.e) And government spending did rise faster, 56 per cent, than the GDP per capita, 39 per cent. But, according to the available figures, which differ rather dramatically according to source, the government of Chile in 1940 was either 12.5 per cent or 5.7 per cent of the GDP in 1940. (Appendix II.1.e) Mexico's was 7.2 per cent. (Appendix II.2.e) In short, Chile's government was relatively the same size or relatively much larger than Mexico's despite all the Cardenista reforms. But wait, things get stranger still. The ironic outcome of these comparisons is that by the end of the 1940s, when both governments were cracking down on radical labor movements and cooperating with the United States government in its Cold War policies, government spending in Chile was expanding more rapidly than that of Mexico: Chile's government more than doubled its economic size, that of Mexico rose about 44 per cent. (same appendices) Obviously, the expansion of the GDP played a role in this change, but it was also due to a deliberate expansion of government as an engine of change in Chile. By 1950, the breakdown of the GDP indicates that the government of Chile was once again relatively larger 10 10 than that of Mexico. To me, the Appendices II.1 and II.2 also indicate something of great interest to the historian: the sectoral structure of the economy of each country remains remarkably similar from the 1920s through the 1940s. Unfortunately, the indices I have for Chile are discontinuous in terms of sources but each index does not change much within its own terms. By 1950, agriculture and mining made up less of the economy of Chile and industry was substantially but not decisively larger. The overall structure of the Mexican economy changed even less, with mining and petroleum falling to five per cent of the economy at the end of the period and manufacturing rising from 10 to 17 per cent in these years. Populism was not a matter of economic recovery nor about the size of government. It was more a matter of symbols, of governmental economic intervention in a market economy, and of delivering some benefits as a political down payment for the future. Latin American populism in the 1930s may have served a very different function than it did in the region after World War II. The intense moments of populist activism were brief in each nation, but the memory of those moments had a long trajectory. Groups remained loyal long after government policies had turned against them. Can anyone make the case that peasants in Mexico remained better off in the 1940s as a result of land reform in the 1930s? Perhaps. Obviously, the starkest contrast in the populist legacy of both nations is that in this era there was no land reform in Chile and unionization of rural laborers was repressed. The urban context is a little more similar. Even as both governments grew, it is clear from the research of Jeff Bortz on Mexico and from the existing tables on real wages in Chile that urban workers suffered substantial reversals of fortune in the 1940s.(Chile 1940-1955; Bortz 1986) There was much talk of "socialism" in both countries during the 1930s but this had nothing to do with a command economy or government control of the means of production. In each nation, it was a tactic for extracting concessions from business interests -- even Alessandri called himself a socialist -- while expanding the role of government. Still, to return to comparison, the role of the national government -- always relatively larger in Chile than in Mexico -- developed in a very different domestic context in each nation. In Chile, the government was in a recovery mode throughout the 1930s so that even as it expanded, it remained incapable of reviving the boom era of the late 1920s. In Mexico, the expansion was a historic first in the simple sense that the government was moving beyond the size and function of any earlier era. But in each country, this governmental expansion left public administration as a significant but minor economic player. Indeed, most of the economy in both nations remained outside the sectors so often stressed by economic historians: industry, agriculture, construction, et. al. One wonders looking at such data as that of Appendices II.3.g and II.4.g what might have happened had governments come up with a means to expand the dynamism of retail trade and commerce (about 20 per cent of Chile's economy and 30 per cent of Mexico's)? These sectors, obviously intertwined with industrial changes, exceeded the size of industry well into the 1940s; 11 11 nor do we possess conclusive evidence that industry was driving the expansion of these sectors. In conclusion, there is the single most important element within the political life of each nation: the persistence of the spoils system based on a multiplicity of parties in Chile, one whose history turned on the formation, deformation, and decomposition of party coalitions; and the rise of that great mutating monster, the PRI, in Mexico, based on patronage but able constantly to relegitimize itself as the legacy of Revolution and of stability. These differences had enormous repercussions in the structure of access to government and influence-peddling. The situation with regard to labor and peasants in both countries has been mentioned. At the other end of the social spectrum, industrialists and landlords retained enormous power but with a major distinction. In Mexico, industrialists lobbied through channels that supported the PRI’s candidates but did not control either the party or the candidates directly. Landlords retained enormous regional power – including their own armed guards into the 1930s – but they lost their seat at inner councils of the executive branch of government. Both groups could be surprised by sudden changes in economic policy.(Story 1986,p54; Knight 1994,p109-110) This difference in institutional structures had enormous importance for the middle class that counted on employment as the state expanded. Middle class rewards in both countries seem to outrun benefits to the working class by the late 1940s. In Chile, the number of laborers covered by social security rose 69 per cent between 1935 and 1955; the number of public employees covered rose 180 per cent, and the number of private white collar employees rose 240 per cent.(Arellano 1985) In both countries, the middle class turned on labor in the Cold War. But fights over spoils in Chile and labor repression eventually cost the Radicals the key middle class, and with that loss, the presidency. The middle class in Mexico goes on accommodating itself to the shifting coalitions within the PRI and the presidency grew ever stronger. Executive stability provided the basis for policy continuities that sustained government inputs for the “miracle” in the 1950s and 60s. All of this has implications for any interpretation of corporatism and populism. Each state was dealing with the massification of politics, each tried to delimit popular pressures. Mexico found in a very strong executive system and a hierarchical party structure the combination to maintain some social peace while funneling substantial investment by the state and foreign capital into industry, irrigated agricultural estates, and infrastructure. Contrary to the assertions of Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards, not every populist experiment in Latin America ended badly.(Dornbusch and Edwards 1991) The question of success turned on whether or not a state could channel popular demands (or repress them) without too high a cost to itself. Mexico confronted labor and peasants with a choice, leave the party and you loose all political legitimacy. In Albert Hirschman’s phrasing, the cost of “exit” became too high.(Hirschman 1970) What is more, the state had acquired a nationalist legimacy in the oil expropriation of 1938 that cemented popular sentiment that this was not a democratic government but it did defend Mexico itself Chile, however, lacked all these qualities. Labor was never incorporated into a dominant party and was repressed broadly in 1948 when the objective target was the Communist Party – the tactic cost the government labor legitimacy for years. Peasants were excluded altogether and remained tied to the servility of inquilinaje. The masses had a stake in the system but paid no 12 12 price for leaving any party – the result was a “fluid” situation as military men describe it. I would suggest one other modification. In contrast to the views often argued by dependistas such as Andre Gunder Frank, the depression did not represent a fundamental break toward greater economic autonomy.(Frank 1967; Arellano 1985) During the crucial moment of 1929-1932, a significant element in regime survival and, therefore, in the overall development of the political economy was not in breaking ties to the United States but in strengthening them. The United States, despite strong Republican opposition to the "bolsheviks" in Mexico City, improved relations with Mexico, opposed or neutralized Calles' enemies, and permitted the Mexican government to suspend debt payments without retaliation. In Chile, neither Ibáñez nor the governments that followed him were able to articulate a set of policies that simultaneously built support at home and won at least acceptance from the United States. President Alessandri (1932-1938), the most successful of Chile's chief executives during the Depression, was unable to elect a successor. Conservative corporatism was never cemented into the political system as it was in Mexico. There is ample evidence, in short, that the Depression did not constitute a break in the role of the United States in Latin American development. Ironically, too, for all the rhetoric about Mexican nationalism, it was Chile which ran most afoul the United States during World War II, while Mexico became much closer to the U.S., a factor that helps explain its rapidly growing exports in the war. Neither political system by the late 1940s was managing to maintain populist gains for the working class, and in both nations, the workers, especially those on the left, made demands for betters wages and conditions and were repressed. That having been said, before 1950, the political system in Mexico did not deliver an "economic miracle" in comparison to Chile. But during the 1940s, it did begin to dramatically expand those industry and agriculture that paid high dividends for the next twenty years. A more intensive populism and a one-party state, therefore, proved to be more successful in some economic terms than a more expansive government with a multiparty system. But the course of this relative success was neither uniform nor predictable. In short, one political economy had not developed some clearly superior direction before 1940 (or even 1950) than the other, but each nation had set itself up for a different form of politics that had far-reaching economic consequences. A central element to the entire story is how each political system went into the Depression, another is the links of export-oriented growth and foreign credit. Mexico's government was relatively smaller and more cohesive than Chile's; this was true before the crash and made a difference once the depression descended. And, as a result, the government was not as vulnerable to a downturn in export earnings as the more trade-dependent Chile.. In addition, Mexico had already made itself a pariah in international financial circles, it had to follow much more conservative fiscal and borrowing policies in the late 20s and so its government did not suffer the destabilizing cut-off of international credit that hit Chile. Chile's conservative corporatist regime, so popular among U.S. investors in the 1920s, intensified the fiscal and political vulnerability of the country to the international economy, while Mexico's "revolutionary" regime laid the groundwork for the most successful, market-oriented, political 13 13 party in Latin American history. APPENDICES Appendix I.1: Chile Gross Domestic Product, 1925-1948 a: Population in Thousands b: Millions of 1977 pesos c: GDP Index 1925-27 ave = 100 d: GDP Per Capita Index 1925-1927 ave = 100 Year a: b: c: d: 1925 3929 61223 96 98 1926 3977 62776 100 99 1927 4034 66614 105 103 1928 4118 82788 130 126 1929 4199 91378 144 136 1930 4287 81600 128 119 1931 4322 67711 106 98 1932 4375 49527 78 71 1933 4420 57659 91 82 1934 4446 69813 110 98 1935 4485 74290 117 104 1936 4530 75295 118 104 1937 4572 88271 139 121 1938 4618 84707 133 115 1939 4645 86809 136 117 1940 5024 91469 144 114 1941 5094 91560 144 113 1942 5130 94945 149 116 1943 5237 98932 156 118 1944 5273 100317 159 119 1945 5349 109446 172 128 1946 5430 116232 183 134 1947 5525 108444 171 123 1948 5620 120915 190 135 Data for Chile are derived from the National Statistics by Sebastian Sáez, La economía política de una crisis: Chile, 1929-1939 (Santiago: CIEPLAN, Notas Técnicas no. 130, Mayo de 1989), 14 14 8; Sáez also incorporated data from the classic study of Raúl Prebisch, United Nations, Economic Survey of Latin America 1949 (New York: United Nations, Economic Commission for Latin America, Department of Economic Affairs, 1951), 272ff. and four other studies of the GDP; data for period after 1940 is from ECLA figures as presented in James W. Wilkie and Carlos Alberto Contreras, eds., Statistical Abstract for Latin America (Los Angeles: U.C.L.A., Latin American Center Publications, 1993), v. 29, part 2, 1290. Appendix I.2: Mexico Gross Domestic Product, 1925-1948 a: Population in thousands b: Millions of 1960 Pesos c: GDP Index 1925-27 ave = 100 d: GDP Per Capita Index 1925-1927 ave = 100 Year a. b: c: d: 1925 15280 37402 97 99 1926 15527 39646 103 103 1927 15776 37902 99 97 1928 16237 36137 94 90 1929 16291 36662 95 91 1930 16554 34364 89 84 1931 16776 35503 92 85 1932 17017 30207 79 72 1933 17274 33620 87 79 1934 17550 35809 93 83 1935 17847 38549 101 87 1936 18167 41633 109 93 1937 18861 43011 112 94 1938 18501 43708 114 94 1939 19280 46058 120 97 1940 19653 46693 122 96 1941 20232 51241 134 103 1942 20289 54116 141 108 1943 21443 56120 146 106 1944 21075 60701 158 117 1945 22726 62608 163 112 1946 22396 66722 174 121 1947 24086 69020 180 116 1948 24796 71864 187 117 Data for Mexico are derived from: Enrique Cárdenas, La industrialización mexicana durante la gran depresión (México: El Colegio de México, 1987), 194-195; Cárdenas, in turn, derived his 15 15 figures from an internal study by the Banco de México. Population figures are from the United Nations, Economic Survey ... 1949, 408-409. Appendix II.1: Breakdown of Chilean Gross Domestic Product by Principal Sectors. Percentage of GDP, 1925-195 Index for 1925-1940, 1925-27 = 100 Index for 1940-1950, 1940 = 100 a. Agriculture and cattle b. Mining and/or Petroleum c. Industry and/or manufacturing d. Construction e. Government f. Rest a: b: c: d: e: f: 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940 ------------1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 18.7 18.6 17.7 17.3 15.3 17.6 17.1 23.8 25.4 20.9 18.1 19.0 16.4 16.6 17.6 16.0 26.8 24.2 21.8 25.0 20.3 20.3 16.6 12.4 13.2 16.7 18.9 19.3 22.7 21.1 20.1 20.7 13.2 12.0 10.9 9.1 7.2 9.6 9.3 12.9 12.4 10.9 12.2 12.9 11.5 12.5 12.4 13.6 1.7 2.4 2.3 1.8 2.3 3.3 1.3 2.4 2.7 3.7 3.9 3.4 3.5 3.3 4.1 4.4 ---14.5 13.0 20.1 24.1 14.9 11.4 9.2 12.1 11.7 8.9 11.0 11.8 12.5 39.4 43.0 39.8 32.0 24.5 29.7 31.3 33.4 34.5 32.2 33.3 33.6 36.9 35.5 33.9 32.6 16.0 14.8 15.3 16.8 15.0 13.5 14.8 14.5 15.4 14.7 9.0 9.0 7.5 7.4 7.0 5.9 5.8 6.4 6.9 6.0 17.5 17.5 21.0 21.4 21.7 22.8 20.9 22.2 22.7 23.7 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.4 2.9 2.7 3.8 3.0 2.5 2.6 5.7 5.7 6.6 6.3 6.3 6.9 6.5 7.6 6.3 7.0 37.8 46.3 46.7 45.6 46.9 48.0 48.7 46.2 46.1 45.9 16 16 1950 13.7 5.8 22.3 2.4 8.7 47.1 Data set 1925-1940, based on Sáez, La economía política de una crisis, 18; data on 1940-1950 derived from Markos J. Mamalakis, Historical Statistics of Chile: National Accounts (Wesport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1978), I, 145-146. Appendix II.2: Breakdown of Mexican Gross Domestic Product by Principal Sectors. Percentage of GDP, 1925-1950 Index 1925-27 = 100 a. Agriculture and cattle b. Mining and/or Petroleum c. Industry and/or manufacturing d. Construction e. Government f. rest a. b. c. d. e. f. 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 10.1 10.7 11.4 11.0 12.1 12.8 11.8 10.2 12.1 12.3 13.3 14.0 13.6 14.3 14.3 15.4 16.5 15.6 15.1 15.9 15.4 16.4 16.1 15.5 16.7 2.4 2.3 2.2 2.6 2.4 2.5 2.1 2.2 2.5 3.1 2.5 3.2 3.1 2.1 3.6 2.5 2.3 2.4 2.3 2.7 2.6 3.8 3.8 3.3 3.4 5.6 5.4 5.6 5.0 4.9 4.9 4.3 5.3 4.7 5.0 5.0 5.9 5.7 7.1 5.5 7.2 6.6 6.2 6.6 7.2 7.0 6.8 6.2 6.0 5.9 50.6 51.1 50.8 51.2 51.9 47.8 52.9 51.9 52.8 51.4 51.6 50.2 50.2 50.1 50.1 50.4 51.0 50.6 51.5 51.8 48.5 53.4 52.1 48.4 56.5 19.7 20.2 20.4 21.2 19.1 18.2 21.1 23.0 21.9 20.3 19.9 19.9 19.1 19.0 19.3 18.0 18.9 19.3 17.8 17.4 16.8 16.3 16.6 18.4 18.4 11.3 10.3 9.3 8.8 9.3 9.2 7.6 7.2 6.9 7.7 7.4 6.9 7.6 7.4 7.0 6.4 5.8 5.8 5.7 4.9 5.1 4.4 5.2 4.8 4.9 17 17 1950 18.1 5.0 17.1 3.6 5.8 50.4 Data for Mexico are derived from Leopoldo Solís, La realidad económica mexicana: retrovisión y perspectivas (México: Siglo XXI, 1993, 20a. ed.), 79-80; Solís derives his figures from the Banco de México. Appendix II.3: Additional Information on Percentages of GDP for Chile, 1940-1950 a. rest in Appendix II b. wholesale and retail trade c. banking and real estate d. ownership of dwellings a. b. 1940 37.8 18.9 1941 46.3 18.3 1942 46.7 19.1 1943 45.1 18.2 1944 46.9 19.2 1945 48.0 19.6 1946 48.7 20.9 1947 46.2 19.3 1948 46.1 17.9 1949 45.9 18.8 1950 47.1 17.7 Data adopted from Mamalakis, I, 145-146. c. d. 4.2 4.2 4.0 3.9 4.1 4.0 3.9 4.1 3.9 2.0 3.9 11.8 10.9 11.3 10.9 10.9 10.7 10.7 9.7 10.0 10.0 10.2 Appendix II.4: Additional Information on Percentages of GDP for Mexico, 1925-1950 f. rest from Appendix II.2 g. commerce f. 1925 50.6 1926 51.1 1927 50.8 1928 51.2 1929 51.9 1930 47.8 1931 52.9 1932 51.9 1933 52.8 g. 29.8 31.1 30.4 30.6 31.1 31.5 32.9 30.6 31.7 18 18 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 51.4 51.6 50.2 50.2 50.1 50.1 29.0 31.1 29.8 30.0 32.6 31.0 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 50.4 51.0 50.6 51.5 51.8 48.5 53.4 52.1 48.4 56.5 50.4 30.9 32.2 31.6 32.0 32.9 32.5 41.7 32.3 29.4 31.5 31.6 Same source as Appendix II.2 Appendix III.1: Indices of Activity by Sector. Chile 1925-1950. Index for data 1925-1940, 1925-1927 = 100. Index for 1940-1950, 1940 = 100 a. Agriculture and cattle b. Mining and/or Petroleum c. Industry and/or Manufacturing d. Construction e. Government (for Chile, 1928 = 100) f. Rest 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 a: b: c: d: e: f: 98 100 101 123 120 124 99 101 106 99 94 135 151 107 73 40 106 99 95 99 108 102 83 84 81 99 120 116 207 160 71 91 ---100 124 136 135 61 88 98 114 96 102 88 77 60 19 19 1933 125 50 94 120 55 1934 133 81 107 214 57 1935 117 92 120 229 75 1936 123 94 127 198 66 1937 122 130 133 238 59 1938 121 116 138 218 70 1939 131 113 141 277 77 1940 125 123 163 316 86 ------------1940 100 100 100 100 100 1941 91 98 119 97 115 1942 99 87 130 97 115 1943 113 87 130 108 120 1944 102 86 136 137 122 1945 100 79 156 141 146 1946 117 82 152 203 144 1947 107 84 150 153 158 1948 128 103 173 143 149 1949 123 90 182 147 167 1950 120 91 180 145 217 Sources: Same as Appendix II, and Mamalakis, Historical Statistics of Chile, I, 151. 72 87 91 92 118 109 107 108 100 121 128 130 136 152 163 144 162 163 176 Appendix III.2: Indices of Activity by Sector. Mexico 1925-1950. Index 1925-1927 = 100. a. Agriculture and cattle b. Mining and/or Petroleum c. Industry and/or Manufacturing d. Construction e. Government (for Chile, 1928 = 100) f. Rest a: b: c: d: e: f: 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 92 103 104 102 102 101 101 75 99 104 99 96 112 102 86 86 75 97 100 100 100 91 85 80 72 76 75 97 104 99 100 97 84 96 80 91 95 104 100 105 90 81 97 90 95 107 104 89 85 86 68 68 55 59 20 20 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 94 99 107 106 108 115 70 75 72 82 82 78 107 125 141 145 151 164 129 111 151 173 179 109 85 92 116 113 113 154 95 102 107 111 112 118 1940 109 75 174 133 1941 125 75 190 137 1942 135 79 205 146 1943 129 81 217 156 1944 136 75 234 188 1945 136 80 242 245 1946 141 74 265 292 1947 148 90 269 298 1948 164 91 286 289 1949 181 94 308 292 1950 195 106 345 344 Data for is table are derived from same sources as Appendix II.2 158 159 159 175 207 213 176 201 215 217 227 121 134 141 148 162 156 183 185 188 220 215 Appendix III.3: Additional Information on Sectoral Indices for Chile, 1940-1950 Mamalakis' Data on Sectors not on Appendix III Chile: f. rest from Appendix III g. wholesale and retail trade h. banking and real estate i. ownership of dwellings 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 f. g. h. i. 100 121 128 130 136 152 163 144 162 163 176 100 96 105 104 112 124 141 121 126 133 133 100 99 99 100 105 112 117 115 122 126 147 100 91 99 99 101 108 115 97 113 114 122 21 21 Data derived from Mamalakis, Historical Statistics of Chile, 145-146, 151. 22 22 Appendix III.4: Alternative Sectoral Indices for Chile, 1925-1950 Ballesteros and Davis Tables: 1925-27 = 100 Chile: a. agriculture b. mining c. industry d. government, 1928 = 100 e. GDP a. b. c. d. e. 1925 91 103 103 96 1926 101 97 98 99 1927 108 99 99 105 1928 128 136 95 100 130 1929 130 147 117 124 144 1930 133 107 117 136 128 1931 117 81 87 135 107 1932 115 45 99 61 78 1933 135 60 109 55 91 1934 142 93 119 57 110 1935 126 103 137 75 117 1936 133 102 140 73 118 1937 138 143 147 65 139 1938 143 129 133 77 133 1939 144 126 151 85 137 1940 140 134 167 85 144 1941 138 158 194 95 160 1942 141 159 202 103 159 1943 146 155 225 83 166 1944 159 154 232 98 171 1945 153 152 288 107 182 1946 154 133 243 129 166 1947 154 150 258 131 180 1948 165 161 283 145 200 1949 160 140 304 188 191 1950 159 137 322 178 196 Indices modified from table in Marto A. Ballesteros and Tom E. Davis, "The Growth of Output and Employment in Basic Sectors of the Chilean Economy, 1980-1957," Economic Development and Cultural Change, XI, 2, part 1 (Jan. 1963), 160-161. 23 23 Appendix III.5: Additional Information on Sectoral Indices for Mexico, 1925-1950 Mexico: Index 1925-27 = 100 f. rest from Appendix III.2 g. commerce f. g. 1925 97 95 1926 104 106 1927 99 99 1928 100 100 1929 97 98 1930 84 93 1931 96 100 1932 80 79 1933 91 91 1934 95 89 1935 102 103 1936 107 106 1937 111 111 1938 112 111 1939 118 122 1940 121 124 1941 134 141 1942 141 147 1943 148 154 1944 162 171 1945 156 175 1946 183 239 1947 185 196 1948 188 191 1949 220 204 1950 215 225 Source, same as Appendix III.2. Appendix IV.1: Raúl Prebisch Latin American Economic Indices. (Original used 1937 = 100; I have changed this to 1925-1927 = 100, which tends to reduce the size of all index numbers. Latin America: a: Quantum of Exports 24 24 b: Quantum of Exports Per Capita c: Quantum of Imports (not available) d: Quantum of Imports Per Capita (not available) e: Price Index of Exports f: Price Index of Imports g: Terms of Trade h: Capacity to Import i: Capacity to Import Per Capita Year a: b: c: d: e: f: g: h: i: 1925 93 95 107 104 102 95 97 1926 97 97 98 102 96 93 93 1927 109 107 95 93 102 111 109 1928 113 109 96 92 104 118 114 1929 120 113 92 91 97 116 111 1930 100 93 70 88 80 80 75 1931 108 99 48 74 65 71 65 1932 90 81 42 59 71 64 58 1933 93 83 45 62 73 68 60 1934 94 82 45 70 90 85 75 1935 103 89 61 71 85 87 75 1936 99 84 61 73 94 93 79 1937 110 92 78 78 101 110 92 1938 100 82 65 77 85 85 69 1939 107 85 64 77 83 88 70 1940 108 74 67 85 79 74 58 1941 103 79 73 91 80 82 63 1942 85 64 89 110 81 69 52 1943 98 72 98 120 81 80 58 1944 110 79 102 132 78 85 62 1945 115 81 105 130 81 93 66 1946 123 85 134 127 106 130 90 1947 127 87 171 149 115 146 100 1948 133 89 180 162 111 147 98 Data is from United Nations, the Secretariat of the Economic Commission for Latin America [ECLA or, in Spanish, CEPAL], Economic Survey of Latin America 1949 (New York: United Nations, Department of Economic Affairs, 1951), 17, 271-279, 408-409,413, 424-439. 25 25 Appendix IV.2: Prebisch data on Chile a: Quantum of Exports b: Quantum of Exports Per Capita c: Quantum of Imports d: Quantum of Imports Per Capita e: Price Index of Exports f: Price Index of Imports g: Terms of Trade h: Capacity to Import i: Capacity to Import Per Capita Year a: b: c: d: e: f: g: h: i: 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 100 90 110 130 138 90 83 39 57 91 93 91 133 125 113 122 136 141 130 134 136 123 124 138 101 90 108 126 131 83 77 36 50 81 82 80 116 107 97 97 106 107 99 101 101 90 89 98 91 123 86 91 116 107 56 20 22 30 44 50 56 61 55 62 60 57 50 54 56 67 75 73 92 123 85 88 110 99 52 18 19 27 39 44 49 52 47 49 47 44 38 41 42 49 54 52 108 100 92 89 85 84 63 46 32 29 32 32 38 33 33 34 37 50 50 53 50 58 65 83 110 86 103 108 116 109 87 68 60 56 58 58 65 69 62 67 72 91 106 107 112 119 144 149 97 114 88 82 73 76 60 52 46 48 50 55 58 48 52 50 51 54 47 49 44 48 45 55 102 108 102 112 107 72 53 22 28 47 50 78 81 63 63 65 73 80 64 69 63 62 58 81 105 104 97 104 97 64 47 19 24 39 42 45 67 52 52 49 54 60 47 50 45 44 40 55 Appendix IV.3: Prebisch data on Mexico a: Quantum of Exports b: Quantum of Exports Per Capita 26 26 c: Quantum of Imports d: Quantum of Imports Per Capita e: Price Index of Exports f: Price Index of Imports g: Terms of Trade h: Capacity to Import i: Capacity to Import Per Capita Year a: b: c: d: e: f: g: h: i: 1925 97 99 109 110 94 96 98 95 96 1926 101 101 103 103 103 100 103 104 104 1927 102 101 89 87 103 104 99 101 65 1928 97 93 92 78 103 106 97 95 67 1929 97 93 98 93 98 108 91 88 84 1930 78 73 78 73 89 125 71 56 57 1931 82 76 52 48 63 111 56 46 35 1932 58 53 39 35 67 132 50 29 27 1933 61 55 46 41 76 144 52 32 32 1934 81 72 55 48 108 170 63 52 37 1935 88 77 61 53 129 176 74 65 41 1936 90 77 71 60 126 188 67 60 47 1937 96 80 89 74 140 198 71 68 57 1938 86 76 58 48 136 247 56 48 48 1939 82 66 69 55 164 260 63 51 43 1940 78 62 65 51 178 296 60 47 40 1941 80 61 96 73 143 281 51 41 57 1942 78 60 70 53 167 313 54 42 41 1943 82 60 82 59 204 310 66 54 46 1944 77 57 127 93 211 317 67 51 72 1945 84 57 147 100 230 326 71 59 77 1946 81 56 196 135 304 391 78 63 107 1947 90 58 201 129 362 461 79 71 100 1948 93 58 161 100 458 532 86 80 78 Sources: In addition to ECLA figures, the Mexican population data is from national census. BIBLIOGRAPHY 27 27 Albert, B. (1988). South America and the Firwst world War: the impact of the war on Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Chile. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Arellano, J. P. (1985). Politicas sociales y desarrollo: Chile 1924-1984. Santiago, CIEPLAN. Askari, H. (1991). Third World Debt and Financial Innovation: the experiences of Chile and Mexico. Paris, Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Barboso Cano, F. (1980). La CROM, de Luis M. Morones a Antonio J. Hernández. Puebla, Editorial Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Bortz, J. (1986). El salario en México. México, D.F., Ediciones El Caballito. Bulmer-Thomas, V. (1994). The Economic History of Latin America since Independence. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Camín, H. A. and L. Meyer (1989). A la sombra de la revolución mexicana. México, D.F., Cal y Arena. Cárdenas, e. (1987). La industrialización mexicana durante la gran depresión. México, D.F., El Colegio de México. Cárdenas, E. (1994). La hacienda pública y la política económica, 1929-1958. México, D.F., Fondo de Cultura Económica. Cárdenas, E. (1994). La hacienda pública y la política económica, 1929-1958. México, D.F., El Colegio de México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. Cardoso, C. (1980). Características fundamentales del período, 1880-1910. México en el siglo XIX (1821-1910): historia económica y de la estructura social. C. Cardoso. México, D.F., Editrial Nueva Imagen. Carr, B. (1981). El movimiento obrero y la política en México, 1910-1929. Mexico City, Ediciones Era. Chile (1929). Archivo Nacional, Oficios. Reglamento para contratos de obras públicas. 328. Chile (1929-1940). “Archivo Nacional. Interior.” . Chile (1940-1955). Anuario estadístico. Santiago. Clark, M. R. (1934). Organized Labor in Mexico. New York, Russell and Russell. 28 28 Córdova, A. (1980). La clase obrera en la historia de México: En la época de crisis (1928-1934). Mexico City, Siglo Veintiuno. Córdova, A. (1981). En una época de crisis, 1928-1934. México, D.F., Siglo XXI. Córdova, A. (1995). La revolución en crisis: la aventura del maximato. Mexico, D.F., Cal y Arena. Cortés Conde, R. and S. J. Stein (1977). Latin America: A Guide to Economic History, 18301930. Berkeley, University of California Press. de Sousa, A. (1978). The Nature of Corporatist Representation: Leaders and Members of Organized Labor in Brazil. Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dornbusch, R. and S. Edwards, Eds. (1991). The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press. Ffrench-Davis, R. (1973). Políticas económicas en Chile, 1952-1970. Santiago, Ediciones nueva Universidad, Universidad Católica de Chile. Frank, A. G. (1967). Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America: Historical Studies of Chile and Brazil. New York, Monthly Review Press. Garrido, L. J. (1991). El partido de la revolución institucionalizada; la formación del nuevo estado en México (1928-1945). México, D.F., Siglo XXI. González Casanova, P., Ed. (1983-1986). La clase obrera en la historia de México. México, D.F., Siglo XXI. González, L. (1979). Historia de la revolución mexicana. Los artífices del cardenismo. México, D.F., El Colegio de México. González, L. (1981). Historia de la revolución mexicana. Los días del presidente Cárdenas. México, D.F., El Colegio de México. Haber, S. H. (1989). Industry and Underdevelopment: The Industrialization of mexico, 18901940. Stanford, Stanford University Press. Hall, L. B. (1995). Oil, Banks and Politics: The United States and Postrevolutionary Mexico, 1917-1924. Austin, University of Texas Press. Hamilton, N. (1982). The Limits of State Autonomy: Post-Revolutionary Mexico. Princeton, 29 29 Princeton University Press. Heise González, J. (1974). Historia de Chile, La República Parlamentaria, 1861-1925. Santiago, Editorial Andres Bello. Hernández Chávez, A. (1979). Historia de la revolución mexicana. La mecánica cardenista. México, D.F., El Colegio de México. Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Knight, A. (1991). Mexico's Elite Settlement: conjuncture and consequences. elites nd Democratic Consolidation in Latin America and Southern Europe. J. Higley and R. Gunther. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Knight, A. (1992). “The Peculiarities of Mexican History: Mexico Compared to Latin America, 1821-1992.” Journal of Latin American Studies 24(Quincentenary Supplement): 99-144. Knight, A. (1994). Mexico, c. 1930-46. The Cambridge History of Latin America. L. Bethell. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 7: 3-82. Lehmbruch, G. and P. C. Schmitter, Eds. (1982). Patterns of corporatist policy-making. Beverley Hills, Ca., Sage Publications. León, S. and i. Marván (1985). La clase obrera en la historia de México. En el cardenismo (19341940). México, D.F., Siglo XXI y el Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, UNAM. Loveman, B. (1988). Chile: The Legacy of Hispanic Capitalism. Oxford, Oxford University Press. MacLachlan, C. M. and W. H. Beezley (1994). El Gran Pueblo: A History of Greater Mexico. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall. Maddison, A. (1985). Two Crises: Latin America and Asia, 1929-38 and 1973-83. Paris, Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. Malpica Uribe, S. (1985). El laborismo mexicano (1912-1929). Socialismo y sindicalismo en los orígenes del movimiento obrero latinoamericano. A. J. Pla and S. Malpica Uribe. Puebla, Centro de investigaciones Historicas del Movimiento Obrero, Institutode Ciencias, Universidad Autonoma de Puebla: 164-173. Mamalakis, M. and C. W. Reynold (1965). Essays on the Chilean Economy. Homewood, Il., Richard D. Irwin, Inc. 30 30 Mamalakis, M. J. (1976). The Growth and Structure of the Chilean Ecoomy: From Independence to Allende. New Haven, Yale University Press. Medin, T. (1982). El minimato presidencial: historia política del Maximato, 1928-1935. Mexico City, Ediciones Era. México, A. (1929-1943). “Gobernación, Quejas contra gobierno.” . Meyer, J. (1974). La cristiada. Mexico City, Siglo Veintiuno. Meyer, J. (1986). Mexico: revolution and reconstruction in the 1920s. The Cambridge History of Latin America. L. Bethell. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 5: 155-196. Meyer, J., E. Krauze, et al. (1977). Historia de la Revolución Mexicana, 1924-1928: Estado y sociedad con Calles. México, D.F., El Colegio de México. Meyer, L. (1978). Historia de la revolución mexicana, 1928-1934. El conflicto social y los gobiernos del maximato. Meyer, L. (1978). História de la revolución mexicana. Los inicios de la institucionalización: la política del Maximato (1928-1934). Mexico City, Colegio de México. Monteón, M. (1982). Chile in the Nitrate Era: The Evolution of Economic Dependence, 18801930. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press. Monteón, M. (1998). Chile and the Great Depression: The Politics of Underdevelopment, 19271948. Tempe, Center for Latin American Studies, Arizona State University. Morales-Gomez, D. A. and C. A. Torres (1990). The State, Corporatist Politics, and Educational Policy-Making in Mexico. New York, Praeger. Palma Zuñiga, L. (1963). Pedro Aguirre Cerda: maestro, estadísta, gobernante. Santiago, Editorial Andres Bello. Palma Zuñiga, L. (1967). Historia del partido radical. Santiago, Editorial Andres Bello. Pike, F. B. and T. Stritch, Eds. (1974). The New Corporatism; socio-political structures in the Iberian World. Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press. Portes Gil, E. (1941). Quince años de política mexicana. México, D.F., Ediciones Botas. Puig Casauranc, J. M. (1938). La gelatea rebelde a varios pigmaliones. De Obregón a Cárdenas 31 31 (Antecedentes del fenómeno mexicano actual). México, Impresores Unidos. Reynolds, C. (1970). The Mexican Economy: Twentieth-Century Structure and Growth. New Haven, Yale University Press. Rippy, J. F. (1958). Globe and Hemisphere: Latin America's place in the postwar foreign relations of the United States. Chicago, H. Gergery Company. Ruiz, R. E. (1992). Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexico People. New York, W. W. Norton and Company. Salamini, H. F. (1978). Agrarian Radicalism in Veracruz, 1920-1938. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press. Salazar, G. (1990). La violencia política en las "Grandes Almedas, 1947-1987. Santiago, Ediciones SUR. Story, D. (1986). Industry, The State, and Public Policy in Mexico. Austin, University of Texas Press. Tamayo, J. (1987). La clase obrera en la historia de México: En el interinato de Adolfo de la Huerta y el gobierno de Alvaro Obregon (1920-1924). Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Instituto de Investigaciones sociales. Thorp, R. (1992). “A Reappraisal of the Origins of Impost-Substituting Industrialisation, 19301950.” Journal of Latin American Studies 24(Quincentenary Supplement): 181-195. United States, R. (1929-1930). General Conditions/18. No. 379G, Report on General Conditions Prevailing in Chile, 1 Dec. 1929- 31 Jan. 1930. J. G. Lay. Whitehead, L. (1994). State Organization in Latin America since 1930. The Cambridge History of Latin America. L. Bethell. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 6, part 2: 3-99. Wiarda, H. J. (1981). Corporatism and National Development in Latin America. Boulder, Co., Westview Press. Wiarda, H. J. (1997). Corporatism and Comparative Politics: the other great "ism". New York, M.E. Sharpe. Wiarda, H. J. and H. F. Klein, Eds. (1996). Latin American Politics and Development. Boulder, Co., Westview Press. Williamson, P. J. (1985). Varieties of Corporatism: A Conceptual Discussion. Cambridge, 32 32 Cambridge University Press. Womack Jr., J. (1978 Winter). “The Mexican Economy During the Revolution, 1910-1920: Historiography and Analysis.” Marxist Perspectives 1(4): 80-104. Zevada, R. J. (1971). Calles, el Presidente. Mexico, D.F., Editorial Nuestro Tiempo, S.A. Zimerman, G. L. (1991). Los pactos obreros y la institución presidencial en México, 1915-1938. México, D.F., Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana - Azcapotzalco, Sección Editorial. links presidentialism to various pacts with labor organizations