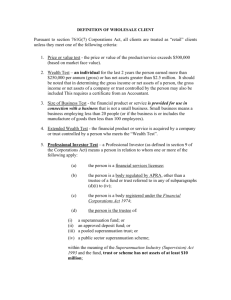

Taxation (Annual Rates, Foreign Superannuation, and Remedial

advertisement