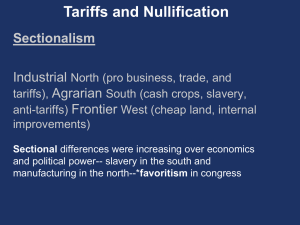

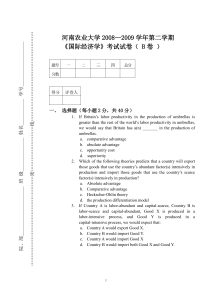

Define the theories of International trade

advertisement