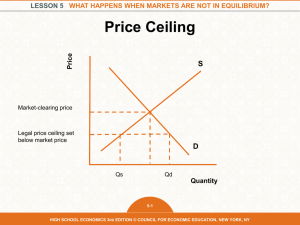

EFFECTS OF RECENT PRICE CEILING ON THE SUPPLY AND

advertisement