скачати

Existentialism In Grendel Essay, Research Paper

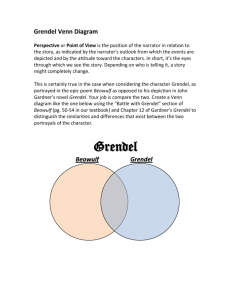

The debate between existentialism and the rest of the world is a fierce, albeit recent one. Before the “dawn of science” and the Age Of Reason, it was universally accepted that there were such things as gods, right and wrong, and heroism. However, with the developing interest in science and the mechanization of the universe near the end of the Renaissance, the need for a God was essentially removed, and humankind was left to reconsider the origin of meaning. John

Gardner?s intelligently written Grendel is a commentary on the merits and flaws of both types of worldview: the existentialist “meaning-free” universe, and the heroic universe, where every action is imbued with purpose and power. Indeed, the book raises many philosophical questions in regards to the meaning of life as well as to the way humans define themselves. Additionally,

Gardner portrays continual analysis, and final approval, of existentialist viewpoints as one observes that the main character, Grendel, is an existentialist.

After having thoroughly read the book, there is no doubt that Grendel shows proof of support in existentialism. The novel follows the life of a character who is gradually “disillusioned,” turning from a teary romantic into a cold nihilist. Indeed, as the main character describes his childhood/adolescence in the beginning of the novel, his naivet? and innocence clearly stand out.

?And so I discovered the sunken door, and so I came up, for the first time, to moon light?, recalls

Grendel, remembering his first days out on earth as he analyzed and discovered various creatures and his surroundings with blatant ignorance (16). With the story of his first encounter with men, after getting his foot stuck in a crack where two old tree trunks joined, Gardner demonstrates

Grendel?s innocence (he yells for his mother and cries ?Mama! Waa!?) as well as his urgent need to define things and find a meaning for himself.

Through his eyes are shown the futility of a romantic outlook and the destruction of a dream. “If the Shaper’s vision of goodness and peace is a part of himself, not idle rhymes, then no one understands him at all,” thinks Grendel, recognizing the divergence between reality and the heroic ideal (53). His defeat of Unferth marks the symbolic destruction of heroism, at least in his head; “So much for heroism,” he concludes (90). Even Grendel’s existence would seem to disprove the notions of the Shaper, who preaches the virtues of honor and courage. If the world is based on right and wrong, how can Grendel continue to survive? How can he kill senselessly every night, bring so much grief and torment to humans, and yet nothing come of it? “It’s all the same in the end, matter or motion, simple or complex,” whether he kills or not (73). In the beginning, Grendel decides that life must be devoid of meaning. Nihilism is, of curse, a rather depressing, if liberating, way to go through life, but such would seem to be the conclusion of the book.

In order to understand what Gardner intends by this, one must look at the process through which

Grendel turns nihilist. Psychologically, Grendel is an interesting character. He spends his entire life practicing the denial of truth. His first interaction with humans, conscious, thinking beings like himself, forces him to turn to philosophical solipsism in order to cope with their existence.

Life stays much simpler if he can still pretend that he is the only thing that matters; ?he exists, nothing else” (28). With the coming of the Shaper, Grendel’s inner romanticism awakes and he briefly pulls back from the edge of cynicism. The Shaper’s “honeysweet lure” has a kind of meaning beyond truth for which Grendel longs (48). Despite his inner arguments and the evidence of human brutality all around him, especially as he recollects the growth of Hrothgar’s

Kingdom, Grendel surrenders himself to romantic ideals. ?Now and then some trivial argument would break out, and one of them would kill another one, and all the others would detach themselves from the killer as neatly as blood clotting?? (32). But he cannot keep this up in the face of so much human cruelty, and slowly begins the conversion to cynicism. When the dragon arrives, his vague cynicism takes a new direction: nihilism. ?Futility, doom, became a smell in

the air, pervasive and acrid as the dead smell after a forest fire; my scent and the world?s…?

(75). Yet Grendel still protests the idea that his actions are meaningless, refuses to commit himself fully to the world of the Shaper or dragon, or even an internal notion of truth.

His indecision combines with his feelings of rejection and Grendel becomes angry at the world for being so confusing. “An angry man does not usually shake his fist at the universe in general.

He makes a selection and knocks knocks his neighbor down” (69). Because of this anger,

Grendel kills. But even though he acts without regard for any moral implications, his killing, like any action, still has meaning, if only by the fact that he chose to kill. It is, in essence, a misguided attempt to deny the meaninglessness of life by destroying it. His continued attempts at reducing meaning are illustrated in many forms. He eats the priests, reducing religion to something that “sits in the stomach like duck eggs” (129). He humiliates Unferth, reducing heroism to a whimpering man. This ultimately comes to Grendel’s attempted murder of

Wealtheow, their queenly female ideal. Even though he concludes that killing her “would be as meaningless as letting her live,” the fact that he willingly chooses the former proves that he has not fully accepted nihilism. Through it all runs a current of desperation and denial; if life is meaningless, why must Grendel go to so much effort to prove it? Why not just do as the dragon advises, “seek out gold and sit on it,” (74) wrapped up in ultimate self-centeredness? The irony of nihilism, and one reason Grendel can never take it into his heart completely, is that it preaches ultimate relativity, yet the end result is non-objectivity, perspective and meaning limited solely to the individual. Confused by what truth is, what meaning is, and what definition is, Grendel finds comfort as he unconsciously embracing the existence of free will. Grendel does not really find meaning to life as the Dragon and Shaper have dictated to him, nor does he seem to veritably believe he is the monster by which the humans define themselves; especially towards his death which he qualifies simply as an ?accident?. In the absence of true meaning, Grendel defines himself partly by conflict. He is the ?meadhall-wrecker?, the ?kingdom-smasher?. He is not human and not normal and not accepted. He is a force of destruction. Even though he has now turned in to what the dragon and shaper have been describing since the beginning of the novel,

Grendel, however, has the impression that because his own will, logic, and decision has he turned into what he is. He has given himself meaning, with no other aid but that of free will.

Consequently, at this point of the book, Gardner cleverly promotes existentialism as he turns

Grendel into a true philosopher appearing much more intelligent and correct than the humans.

Gardner’s refutation of existentialism reaches its rhetorical climax during Grendel’s death.

Beowulf whispers to Grendel, “you make the world by whispers, second by second. Are you blind to that? Whether you make it a grave or a garden of roses is not the point” (171). Once again Gardner poses an interesting question as he introduces Beowulf?s point of view. The Geat warrior does not defend existentialism, but rather challenges it. Beowulf’s point is that the purpose of life lies in meaning, not truth. To Beowulf, existentialism is something completely different in the sense that it is a self-contradiction, for the individual has the power to give life meaning, yet life is meaningless. A conscious being, a “pattern maker” like Grendel, can never accept this fully (27). The belief in nihilism, for any human (or Grendel), is in fact not belief in the absence of meaning, it is belief in the opposite of meaning. In a way, it is the antithesis to meaning and it is neither satisfying, nor objective, nor true for Grendel. Beowulf’s point is that the things, graves, gardens of roses, monsters, and heroes, are no more or less than the meaning given them, which in turn stems from consciousness and life. “The world will burn green, sperm build again. Time is the mind, the hand that makes,” not destroys (170). While Grendel looks for a purpose and reason to life, Gardner’s answer is that life and free will are the source of all purpose and reason, once again promoting an existential viewpoint.

Gardner provides us with a conclusive answer to the existentialism debate in the final scene. The key difference between Grendel and Beowulf, like that between heroism and existentialism, is

meaning. Grendel kills without meaning, and Beowulf kills with meaning. A small difference, indeed, but it is the symbolic distinction between he that dies and he that survives. From

Grendel’s point of view, even his own end is meaningless; it is only an “accident” which happens to him (174). To Beowulf, it is a victory, a triumph, and a rebirth for humankind. Is

Beowulf’s perspective, according to Gardner, necessarily more valid? No. But Gardner also remarks that nihilism, true or not, must end in denial. Finally, he implies that existentialism is very different from nihilism. In a world where definition and meaning are not always clear, many, including Grendel, find comfort in existentialism and the assumption that people are entirely free in their, hopefully optimistic, quest for meaning.

339 http://ua-referat.com