effectual call or causal effect

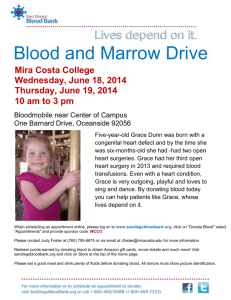

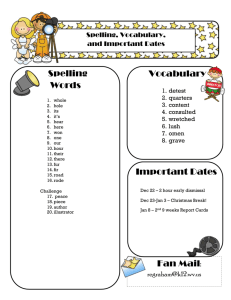

advertisement