CE1515F: Education I - Mary Elizabeth Hess

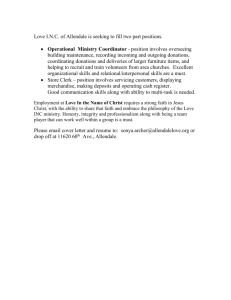

advertisement