Douglas Carmichael speaks out

advertisement

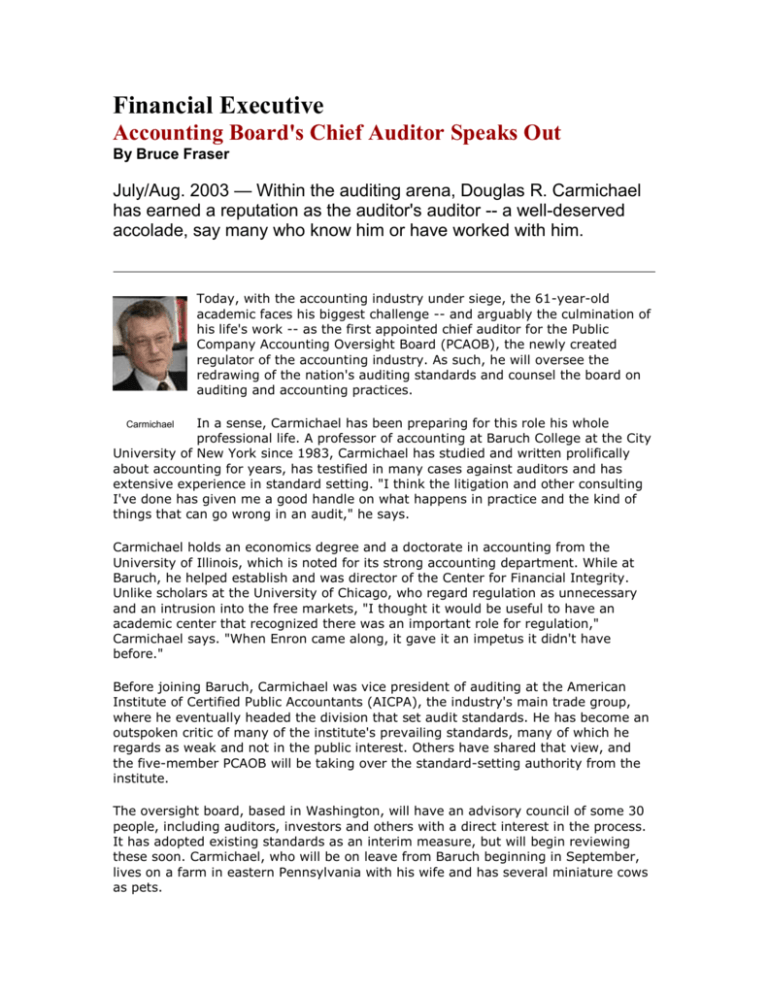

Financial Executive Accounting Board's Chief Auditor Speaks Out By Bruce Fraser July/Aug. 2003 — Within the auditing arena, Douglas R. Carmichael has earned a reputation as the auditor's auditor -- a well-deserved accolade, say many who know him or have worked with him. Today, with the accounting industry under siege, the 61-year-old academic faces his biggest challenge -- and arguably the culmination of his life's work -- as the first appointed chief auditor for the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), the newly created regulator of the accounting industry. As such, he will oversee the redrawing of the nation's auditing standards and counsel the board on auditing and accounting practices. In a sense, Carmichael has been preparing for this role his whole professional life. A professor of accounting at Baruch College at the City University of New York since 1983, Carmichael has studied and written prolifically about accounting for years, has testified in many cases against auditors and has extensive experience in standard setting. "I think the litigation and other consulting I've done has given me a good handle on what happens in practice and the kind of things that can go wrong in an audit," he says. Carmichael Carmichael holds an economics degree and a doctorate in accounting from the University of Illinois, which is noted for its strong accounting department. While at Baruch, he helped establish and was director of the Center for Financial Integrity. Unlike scholars at the University of Chicago, who regard regulation as unnecessary and an intrusion into the free markets, "I thought it would be useful to have an academic center that recognized there was an important role for regulation," Carmichael says. "When Enron came along, it gave it an impetus it didn't have before." Before joining Baruch, Carmichael was vice president of auditing at the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), the industry's main trade group, where he eventually headed the division that set audit standards. He has become an outspoken critic of many of the institute's prevailing standards, many of which he regards as weak and not in the public interest. Others have shared that view, and the five-member PCAOB will be taking over the standard-setting authority from the institute. The oversight board, based in Washington, will have an advisory council of some 30 people, including auditors, investors and others with a direct interest in the process. It has adopted existing standards as an interim measure, but will begin reviewing these soon. Carmichael, who will be on leave from Baruch beginning in September, lives on a farm in eastern Pennsylvania with his wife and has several miniature cows as pets. FE: What is your role as chief auditor of the PCAOB, and how do you plan to work with William McDonough, who will be the permanent chairman, and other board members? Carmichael: My role is to be the primary advisor to the board on accounting and auditing matters. I view that as explaining to them what the real issues are and helping them understand auditing, how it works and what it's supposed to do. It's a very important role because it can keep the board from being captured by the accounting industry. Some groups established in the past were supposed to set the standards on accounting, and instead were captured by the industry FE: The PCAOB has had a rocky start with the controversies surrounding former SEC Chairman Harvey Pitt and onetime PCAOB nominee William Webster. Will this hinder its effort going forward? Carmichael: I don't think it will. That might have happened, but the four board members who were appointed assumed a lot of the initiative. Each one took on a particular area of responsibility to see things got accomplished. Much was accomplished that might have languished without acting Chairman Charlie Niemeier's leadership and their collective efforts. McDonough was appointed shortly before I accepted the job. I made a point of talking with him before I accepted it. I found he has the same concern I do with protecting investors, and a desire to see the standards set in the public interest with protection of investors as the primary goal. I anticipate no difficulties in working with him and advising him on auditing policy. FE: Do you think the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the new system it put into place, including the board, went far enough to curb accounting abuses? Carmichael: The main feature of Sarbanes-Oxley was the creation of the PCAOB. The best approach to deal with the accounting scandals is to set up a mechanism to do the things that the PCAOB will do, to set tighter standards, to make sure the CPA firms are implementing those standards and to investigate apparent abuses of the standards. The ultimate goal of Sarbanes-Oxley is to raise investor confidence and restore trust in independent auditors. The primary means of doing that is the PCAOB. In writing legislation today, it would be impossible to anticipate what tomorrow's accounting scandal is going to be. You need a flexible mechanism to deal with problems as they develop. A good example would be requirements on independence. It would be impossible for writers of the Act to contemplate every non-audit service that might impair independence. The PCAOB can deal with new perceived impairments of independence as they arise. FE: What is the board's relation to the SEC? Carmichael: The board is overseen by the SEC. The primary advisor to the SEC on technical matters is the chief accountant. The chief accountant has the primary responsibility for advising the commission on accounting matters. The SEC has relied primarily on the AICPA for developing [auditing] standards, and now that has changed. I anticipate working closely with the new chief accountant on key auditing issues. The three primary activities of the PCAOB going forward will be the registration and inspections of accounting firms, standard setting and investigations. FE: What new audit standards are you likely to back, and why? Carmichael: We're going to be engaged in implementing rules on internal controls. Section 404 of Sarbanes-Oxley mandates that management of public companies must report on the effectiveness of their internal controls over financial reporting. Management has to sign off not only on their financial statements, but also on the quality of the controls over the system used to create financial statements. In addition to management's report, the Act requires that there be a report by the independent auditor on whether management's report fairly states the situation. We're also certainly going to look at the new standard on fraud detection issued by AICPA to see whether it needs improvement. Another thing we need to do is take a look at the requirements for "auditor documentation." That's the record the auditor makes of the work done. That will be coordinated with our inspections. In addition, we have to look at whether there needs to be new audit requirements to ensure that the correct relationship exists between the auditor and the audit committee. Sarbanes-Oxley mandates that the audit committee hires and fires the independent auditor, and that the independent auditor views the audit committee as the primary client. The audit committee, in turn, is supposed to represent shareholders and potential shareholders. Another thing we need to look at is whether we need more guidance on auditors' involvement with earnings releases. Now, there are no standards on auditor involvement, so a company can put out a release on earnings without it being cleared by the independent auditor. More important, the auditor's responsibilities aren't spelled out for situations in which the auditor disagrees with management's disclosures in the release. FE: What kind of enforcement powers will the board have? Carmichael: The primary enforcement power comes from the fact that in order to audit public companies, CPA firms have to be registered with the board, and the board's powers include the ability to remove that registration. That could be done for varying periods of time. FE: What would be grounds for lifting a firm's registration? Carmichael: A systematic breakdown in the firm's oversight of its audits that the board detected, or repeated unreasonable audit failures. FE: Do you expect accounting firms will lead in going along with the new standards, or do you foresee foot-dragging? Carmichael: I think it's going to be mixed. Some firms have already expressed an interest in going beyond existing standards, for example, in fraud detection, but I'm sure others will resist making standards tighter. Our goal is certainly to have the standards be definitive and set clear requirements. FE: What about conflicting interests that can arise when accountants act as consultants to companies whose financial statements they scrutinize, such as happened at Enron, WorldCom, etc. What kind of additional rules will you propose to buttress the independence of accountants? Carmichael: The new rules on independence in Sarbanes-Oxley, and [those] the SEC subsequently adopted, already place significant restrictions on providing non-audit services. I don't think we're going to have any wholesale ban on non-auditing services, but we're going to continue to look at important issues as they arise. Providing tax-shelter advice to audit clients and their officers would be one specific problem area that would have to be looked at. Another would be the kind of help that an auditor could provide an audit client in documenting internal controls and correcting weaknesses in those controls. Another [issue] is rotation of auditing firms. Sarbanes-Oxley requires the GAO [General Accounting Office] to study that issue. The only rotation now is of the lead partner and concurring [or second] partner, and that has to be every five years. The issue is whether that is sufficient, or to decide if the audit firm itself has to be rotated. FE: Will audit committee members' increased responsibilities increase their possible liability? Carmichael: Any time there are increased responsibilities, there is a risk that those who don't meet their responsibilities will have liability. So, I think there are increased risks, but that a competent and diligent member of the audit committee who takes his or her responsibility seriously should not have any real concern about liability. Personally, I believe that it would be worthwhile for audit committee members to exercise the right that the Sarbanes-Oxley Act gives them to hire their own individual advisors. FE: Stock options are a divisive subject right now. Currently, U.S. public companies can choose whether to expense them in their earnings or not. Which side are you on, and why? Carmichael: I'm on the same side as Warren Buffett - that stock options should be recognized as an expense in the income statement. When stock is used as an incentive for management or employees, it's as much an expense as using stock to acquire goods or services. I think it's always better that financial statements portray reality. FE: Do you favor allowing companies to be able to continue issuing earnings on a "pro forma" basis? Carmichael: People haven't recognized that a lot of pro forma adjustments were misleading. It's been a way to fool investors. [The SEC has] put certain restrictions on including those numbers in SEC filings. I'd like to see how the new SEC rules work, but as a general matter, pro forma information has been an area of abuse in the past, and if the new rules don't significantly reduce those abuses, more restrictions will be necessary. FE: Do you favor proposing new rules or changes in the election of directors and audit committee members? Carmichael: Sarbanes-Oxley and the SEC's implementing rules are going to lead to improvements in corporate governance, and I'd like to see how those new rules work before considering whether more are necessary. The new rules require disclosure of whether a member of the audit committee qualifies as a financial expert. That will put more pressure on corporations to have financial experts on the board and the audit committee. The primary relationship between the corporation and the auditor is supposed to be with the audit committee. We need to see whether that brings about a substantive change in the auditor-client relationship. FE: Do you think the risk is you'll be too hard on the accounting firms, setting standards too high for what accountants are expected to review and discover? Carmichael: One of the purposes of the board's advisory group is to get input from preparers of financial statements and auditors, but in setting requirements, the really important thing is that those requirements be clear. As long as auditors know what they are required to do, having those responsibilities should not surprise them. BRUCE W. FRASER is a New York-based financial writer whose writing credits include CNBC.com, Forbes.com, Worth.com, Mutual Funds magazine and Christian Science Monitor, among other publications and Web sites. He can be reached at frasernyc@aol.com. Subscribe to Financial Executive! The flagship publication of Financial Executives International (FEI), this premier magazine provides senior financial executives with financial, business and management news, trends and strategies to help them work better, faster and smarter. For more information about FEI, visit www.fei.org. FEI's flagship publication, Financial Executive magazine, has won another award -an Eastern Regional gold (first place) award from the American Society of Business Press Editors (ASBPE) in their annual competition. FE won in the editorial division for its March 2002 special section on "Best Practices." This is the fourth juried award FE has won in the past two years. The award was presented in Boston on Monday, June 9. © 2003 Financial Executives International. Reprinted with permission