Ch. 16-Constitutionalism in England

advertisement

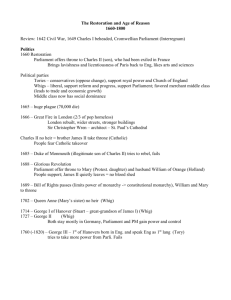

Constitutionalism in England England Turned Upside Down, 1642–1660, pp. 498–502 Charles I vs. Parliament Charles I (r. 1625–1649) wanted to establish absolutism in England. In 1629, when Parliament wanted Charles to agree to the Petition of Right (a promise not to levy taxes without Parliament’s consent), he closed Parliament for eleven years. He irritated Puritans by favoring Anglican rituals similar to Catholic rites. Court of Star Chamber When the same thing was tried on Presbyterian Scots, the Scots invaded the north of England in 1640, forcing Charles to summon Parliament to levy new taxes. Moderate elements within Parliament voted to undo some of the king’s less popular measures. Charles attempted to arrest them, but when opposition arose, he left London to raise an army. Civil War and the Challenge to All Authorities The English civil war began in 1642. Charles’s army, known as the Cavaliers, found their support in northern and western England. The parliamentary forces, known as the Roundheads, had their stronghold in the areas surrounding and including London. The Puritan Roundheads were led by Oliver Cromwell. In 1646, Cromwell’s New Model Army defeated the royalists at the battle of Naseby. Parliament then split into moderate Presbyterians and radical Independents. The Presbyterians made up the majority, but the Independents controlled the army and used it to purge the Presbyterians from Parliament. The remaining members were known as the Rump Parliament. Other religious and political dissenters included the Levellers, the Baptists, and the Quakers. Many new sects emphasized women’s spiritual equality. Oliver Cromwell In 1648, the Rump Parliament found Charles I guilty of trying to create “an unlimited and tyrannical power.” On January 30, 1649, he was beheaded. The Rump Parliament then abolished the monarchy and formed a republic led by Oliver Cromwell, who tolerated no opposition. He conquered Scotland again and brutally subdued Ireland. He waged war on the Dutch, and, in 1651, enacted the first Navigation Act to protect English commerce against the Dutch. But Cromwell alienated supporters with higher taxes than those imposed by the monarchy and with harsh tactics against dissent. In 1653, Cromwell abolished the Parliament and named himself Lord Protector. In 1660, two years after Cromwell’s death, a newly elected Parliament called Charles II, the son of the beheaded king, to the throne. By the time of Cromwell’s death, he had become highly unpopular due to some of the actions above: dictatorial behavior, such as abolishing Parliament; raising taxes; banning newspapers; persecuting dissent. The Glorious Revolution of 1688, pp. 502–504 Sneak preview of the next three monarchs of England: Charles II (r. 1660-1685), son of Charles I James II (r. 1685-1688), brother of Charles II William and Mary o William (r. 1689-1702) was a Dutch ruler and the Prince of Orange o Mary (r. 1689-1694) was the oldest daughter of James II Back to our story: The Restored Monarchy Although most English welcomed the monarchy back in 1660, many soon came to fear that Charles II wished to establish absolutism on the French model. In 1670, Charles secretly agreed to convert to Catholicism in exchange for money from Louis XIV to fight the Dutch. Although Charles never pronounced himself a Catholic, he did ease restrictions on Catholics and Protestant dissenters. Declaration of Indulgence (1673) In 1673, Parliament passed the Test Act, which required government officials to pledge allegiance to the Church of England. In 1678, Parliament tried to deny the throne to any Roman Catholic because they did not want the king’s brother and heir James, a Catholic convert, to inherit the throne. Exclusion Crisis Charles did not allow this law to pass, splitting Parliament into two factions: o Tories, who supported a strong, hereditary monarchy and the Anglican church; o Whigs, who supported a strong Parliament and toleration for nonAnglicans. Parliament’s Revolt against James II James II succeeded his brother as king and pursued absolutist and pro-Catholic policies. When his wife gave birth to a son that ensured a Catholic heir to the throne, the Whigs and Tories in Parliament united. They offered the throne to James’s older Protestant daughter Mary and her husband, the Dutch ruler William, prince of Orange. In the Glorious Revolution, so-called because it was brought about with relatively little bloodshed, James fled to France, and William and Mary took the throne. o The condition was that they had to grant a bill of rights that confirmed Parliament’s rights in government. o This agreement gave Parliament recognition as a formal, independent body. “Glorious Revolution” refers to the events surrounding the abdication of James II and William and Mary coming to the throne in 1688. The propertied classes that controlled Parliament now focused on consolidating their power and preventing any future popular turmoil. o Toleration Act of 1689 granted all Protestants freedom of worship; Catholics got no rights, but were often left alone to worship privately. Outposts of Constitutionalism o Dutch Republic o British North American colonies