Rational for Housing Subsidies in Emerging Economies

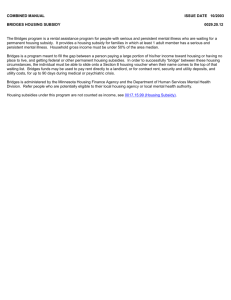

advertisement