Revolution or Transition

advertisement

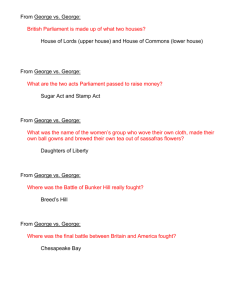

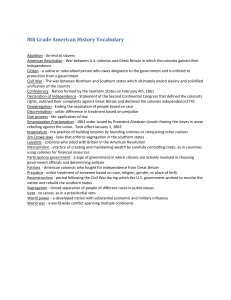

American Independence: Revolution or Transition By Charlie Kroiss The use of the word “revolution” in American Revolution is not entirely apt. “Transition” may describe the American war for independence better. During much of the 17th century, Great Britain’s biggest role in the colonies was regulating trade so that it favored British Merchants. The colonists went about establishing their governments essentially independent from British Politics. Only after the French and Indian Wars, when England found itself in massive debt and began to covet the growing wealth in the colonies, did Great Britain attempt to take active control in America, often imposing requirements and duties on American colonists that were not shared by the English, or in some cases not even legal in England. The works of Patrick Henry, Thomas Paine, and the “Massacre” in Boston, give a feeling that the war was more of a resistance to an invasion from a foreign power, rather than a revolt against an establish government. The conflict started in Europe in the form of hostilities between Britain and France during the War for Austrian Succession, known as King George’s War to the Colonists. In the colonies what would become the French and Indian Wars, started as series of border raids between colonists and the French and their native allies. However while the colonists would succeed in holding pushing back the French, they would face a new trouble from Britain when the British Parliament voted to allow the Royal Navy to “impress”, or involuntarily recruit sailors, without colonial permission, an act that was illegal in England. This much hated practice, which caused Knowles Riot in 1747 in Boston, along with the British restoration of the land seized by the colonist back to the French in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, taught the colonist that their interest were of little importance to England (Ayers pp.115-16). The end of King George’s War would lead into the Seven Years’ War, in which many colonists fought as British citizens. With the conclusion of these wars the colonists felt that they were equal to the citizens of Great Britain and also began to identify themselves as Americans (Ayers p.121). Despite American colonist feelings of equality in stature to those who lived in England, the British Parliament would show again and again that they felt them to be less. In 1764 Parliament would add to the already unfair tax burdens, such as the Woolen Act of 1699 that forbade the colonies to trading woolen goods between one colony and another, the Molasses Act of 1733, taxed exports of American sugar products, and the Iron Act of 1750, which allowed duty free importation of American iron by British Merchants but forbade iron fabrication by American colonies (Ayers p.122). The Sugar Act of 1764 would replace the ineffective Molasses Act by lowering the amount of tax so merchants would no longer risk smuggling, but it expanded the illegal act of writs which allowed the Royal Navy to search ships and warehouses, as well as adding large amounts of bureaucratic paperwork for colonial merchants. In addition Parliament in acted the Currency Act which forbade the Colonies from issuing paper money, creating a shortage of currency (Ayers pp.135-35). As final straw that would push colonists to action, Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, to pay for the standing British army stationed in the Colonies, which during times of peace was illegal in England. The act required that individuals buy stamps to be placed on everything from official documents such as wills and bills of landing to playing cards. In addition to the stamp there was another tax for official transactions and the tax had to be paid in specie or coined money which was in short supply (Ayers pp134-37). The problem with these new taxes was that they were to generate revenue. Colonists understood the British Constitution to say that people must consent to revenue generating taxes through their representatives, of which they had none. As one Philadelphia merchant put it, if the colonists are to be taxed without representation “they are no longer Englishmen but Slaves (Ayers p.136).” In Patrick Henry’s “Speech in the Virginia Convention, 1775” he made a case for independence; however his speech addressed the conflict as if the Colonies were not under British control. He stated that despite the heavy presents of British military, the colonists were unwilling to reconcile, and that if they wished to continue to have the privileges they had previously enjoyed, they must fight (Weise pp 82-83). Thomas Paine took a different approach to get at a similar idea. In “Common Sense, 1776”, he states that America had benefited from its former connection to England. In this work he often uses words like reconciliation and conqueror when describing the relationship between England and America and used the “massacre” and oppression of Boston to back up the description of Britain as a conquering force, saying that they were under constant threat of fire and plunder by government (the British overtaking of public and private properties to house and feed troops)(Weise pp.88-94). While not all colonists agreed with the War for Independence, few could argue that they were on equal standing with, or govern by the same laws that governed England. The original establishment of many of the colonies had led their citizens to be highly independent people, who developed and believed in their own governments. The unfair taxation and subjection to brutal British force would be used to justify independence. England no longer had a legitimate claim to America and the use of force was necessary to remove them from American soil.