Ch'en Ku-ying (Chen Guying), tr

advertisement

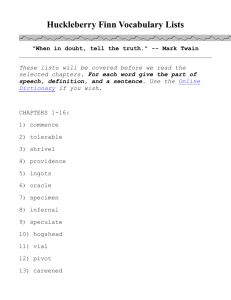

DONE 1. Text-editing and translation philosophy (glossary) + biblio DONE 2. Literature / puns / rhymes DONE3. Cross referencing internal and external (dialogue) 4. Stratification / History / DONE Exclusions DONE 3098 Namelessness wu ming 無名 Stillness jing 靜 Unworked simplicity pu 樸 Return fugui 復歸 Elusiveness Early Dao (27 chapters) No Sage, not Early Dao (30 chapters) Sage 聖人 sheng ren (27 chapters) 32, 37 1,41 --- 15, 16, 37 15, 28, 32, 37 14 16 28 52 45, 26, 61 19 57 28 --- --- --- --- 45 5 1, 61 28 9 hits in 30 chapters 4 hits in 27 chapters 14, 15, 25, 35, 56 Inexhaustibility 4, 5, 6, 35, 52 Female / mother 6, 10, 20, 25, 28, 55, 59 30 hits in 27 chapters xxx Check below UNCLUNK EARLY SAGE / DAO cf 34 LATE 15 HARD TO READ. COMPOSITE INTEGRAL EDITED CHAPTERS ******* YANG ZHU etc. ***** Secret society Disciplined authentication Ca. 275 official collection and official sequence Later 81 chapters (SOME chapters already) Grew like Mass Councils and committees Co-authorship not anonymous Oral disciplined by literate elite No textual piety Duples No original EDITING STRATEGY CHAPTER FORMATION WAVES OF EDITING. DISSEMINATED Early Dao and the rest of the Daodejing 4555 My definition of the early Dao group has changed over time, but there are nineteen chapters (groups I-V here, with the exception of chapter 7 in group V) which I have always regarded as early. Because of the presence of the Sage I have had my doubts about chapter 7, but its opening lines fit with chapters 4 through 6 too well for me to leave it out. Chapters 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 54, and 59 and the tag-endings of some chapters have always seemed so0mewhat problematic, but I ended up including them in the Early Dao group because there’s nowhere else to put them. (the majority of these problematic chapters are found in the GD text and thus cannot be called “late”). I have rearranged the sequence of the chapters and have divided them into subgroups, and I have also divided a number of chapters. The 5000-word text of the DDJ was not gathered and sequenced until about 275-250 BC, and it is my premise that this sequence produced a literary unity at the cost of making the history of the text hard to reconstruct by obscuring the interrelationships of the various passages. Likewise, not only are most chapters composites, but some of them are not chapters at all. The division of the DDJ into 81 chapters was later still, probably during the Han dynasty, and a number of chapters (in terms of my argument, notably chapters 5, 20, and 28) consist of unrelated passages defined as a chapter by an editor aiming at the magic number of 81. My editing was not quite as aggressive as it might seem; my early Dao group includes 22 chapters in their entirety, and only six passages from five chapters have been removed and assigned to a later group. These are the mentions of the Sage in chapters 5 and 28, the opening passages of chapters 20, 56, and 59, and the closing passage of chapter 5. My treatment of chapters 5 and 20 can be justified in terms of the GD text, and only the removal of the two appearances of the Sage contributed to my attempt to define an early Dao group contrasting with the rest of the DDJ. My division of the early Dao into seven groups was mostly for the purpose of presentation and doesn’t usualy represent a claim about the history of the text. The exceptions are groups VII and VIII, which do seem somewhat extraneous to the rest of the group. The selection of chapters was done in terms of the commonly-held theory that the DDJ consists of earlier contemplative material to which didactic and politically-oriented chapters were added. Group I is different than the others and has been put at the beginning because I believe that the school of the DDJ (whatever its other sources) had its origin in Tang Zhu’s rejection of war, public service, and the life of the court. The coherence of groups II-VI, once defined, seems fairly self-evident. Similarities of form and style, shared topics and themes, and the relative or absolute absence of various later themes of the DDJ set them off quite clearly from the rest of the text. Groups VII and VIII are problematic, as I have said -- group VIII especially so since it is primarily made up of passages removed from other early Dao chapters. I have divided the DDJ into four groups in all, which I call early Dao (here), middle Dao, Sage Dao, and final Dao. (The sequence here is not necessarily the sequence of production, though I think that it usually is, but rather the sequence of entry into the text). The contiguous core of the middle Dao group is chapters 38-46; the core of the Sage group is chapters 60-66, and the core of the final Dao group is chapters 67-81, leaving 23 chapters which have not been assigned to any group. Middle Dao rarely mentions the Sage, but compared to early Dao it is more engaged in the world, tending more toward persuasive discourse of a somewhat philosophical type and less toward contemplative poetry. I suspect that this group marks the entry of the school of the DDJ into the Hundred Schools debates. Besides its core in Chapters 60-66, the Sage Dao at least includes chapter 49 and the passages mentioning the Sage cut from chapters 5 and 28. These passages together with chapter 60 are the main chapters within which the Sage is the actual topic of the chapter rather than merely part of the editorial formula “Therefore the Sage....” Chapters 5, 49 and 62 all seem to have been influenced by Shen Dao, and others such chapters include chapter 23 and 27 which I have also put into the Sage group, which now includes 10 chapters and parts of two others. Of all these passages, only chapters 63, 64, and 66 are included in the GD text – none of the Shen Dao chapters and none of the chapters in which the Sage is the topic. In all, the Sage appears in 5 of the 31 GD chapters, which is less than would be expected, and while chapter 19 and part of chapter 5 are included in GD, the sage within these chapters is not included. My belief is that the GD manuscripts were produced at the time when the Sage was just starting to make its presence felt in the DDJ. The final Dao, chapters 67-81, is not included in the GD text at all. In the MWD DDJ there is also a break in the sequence after chapter 66, and I believe that chapters 67-81 are a coherent group. The Sage also plays a role in the final Dao, and it is notable that of the only 6 chapters in which Dao and the Sage appear in the same chapter, half are in this small group. Most chapters of the final Dao are clearly written discussions of a single topic, and these chapters are also consistent in theme. They are more didactic than contemplative and advocate magnanimity, forbearance, peace, mercy, and frugality, and the strategic cunning of Sage Dao is mostly absent. I believe that this final section was added to the DDJ after the Sage Dao chapters were already part of it, and serves to some extent as a corrective to Sage Dao as well as a summation of the book as a whole. Below shows the incidences of a group of key themes in the 27 early Dao chapters as they appear undivided in the traditional DDJ, in chapters outside the early Dao which do not include the Sage, and in chapters which do include the Sage. (This totals 84 because the Sage is seen in chapters 5, 7, and 28 of the early Dao). When I divide chapters the picture is even more striking, with chapter 57 the only Sage chapter including any early Dao themes at all. Namelessness wu ming 無名 Stillness jing 靜 Unworked simplicity pu 樸 Return fugui 復歸 Elusiveness Early Dao (27 chapters) No Sage, not Early Dao (30 chapters) Sage 聖人 sheng ren (27 chapters) 32, 37 1,41 --- 15, 16, 37 15, 28, 32, 37 14 16 28 52 45, 26, 61 19 57 28 --- --- --- --- 45 5 1, 61 28 9x in 30 chapters 4x in 3 of 27 chapters. 14, 15, 25, 35, 56 Inexhaustibility 4, 5, 6, 35, 52 Female / mother 6, 10, 20, 25, 28, 55, 59 30x in 27 chapters Divided Chapters While my treatment of the DDJ has varied greatly over the years, 19 chapters have always been part of the early Dao group, and 53 chapters have never been part of it. Only nine chapters have ever been doubtful, and I ended up including three of them. While I could have defined an early Dao group made up entirely of whole chapters, there are reasons why I wanted to divide a number of chapters. This step is justifiable. The chapterdivisions of the received DDJ have been doubted for some time, and the GD text (ca. 300 BC) confirms these doubts: 8 of the 31 DDJ chapters found in GD are fragmentary. The DDJ’s problematic chapters are either arbitrarilydefined chapters consisting of unrelated passages, or else chapters to which extraneous concluding tags have been added. Many or most chapters of the DDJ are composites, however, so the removal of tags also requires a judgment as to their quality or relevance. Fortunately, my mixed methodology allows this, since my goals are not purely historical and neutral. I have made 15 cuts in 14 of the 22 chapters of the early Dao group, while leaving 8 chapters intact. Four openings, one middle, and ten conclusions have been removed. The GD text provides support for six of the cuts. Four of the cut passages are included in the GD text, and five are from chapters not included in GD. Only three of these cuts -- the passages which include the shengren 聖聖 “Sage” in chapters 5, 7, and 28 -- are important to my definition of the early Dao layer. Chapter 5 is made up of three unrelated passages, only the second of which is part of the GD text. I have included this passage in the early Dao group and have moved the opening passage mentioning the Sage and the concluding passage elsewhere. Chapter 28 is not part of the GD text, but the passage mentioning the Sage at the end is entirely unrelated to the rest of the chapter and I have cut it. Finally, the tag including the Sage at the end of chapter 7 consists of a stereotyped formula also seen in chapters 34, 63, and 66. In chapter 7 this tag takes a naturalistic or cosmological statement about Heaven and Earth (which perfectly fits with the preceding passages from chapters 4, 5, and 6) and interprets it in terms of an entirely different discourse about the career of the Sage. There are many such mixed chapters in the DDJ and I have excluded the rest of them from early Dao, but in this case the dividing line within the chapter is sharp enough, and the continuity with the preceding three chapters striking enough, to justify making the cut. Endings cut: 5, 7, 14, 16, 21, 25, 28, 30, 52, and 55. Beginnings cut: 5, 20, 35, 56. Middle cut: 4. (An identical passage in chapter 56 is kept). Cuts justifiable by GD: 5 (two cuts), 16, 20, 30, 52. Cuts not justifiable by GD: 25, 35, 55, 56. Cuts from chapters not in GD: 4, 7, 14, 21, 28. Arbitrarily-defined chapters: 5, 20, 28, 35, 56. Extraneous tags: 7, 14, 16, 21, 25, 30, 52, 55. Extraneous insertion: 4. These passages (and my reasons for excluding them from early Dao) will be discussed elsewhere; the Sage passages will be important in my discussion of the Sage group in the DDJ. Some of these passages are discussed here: John Emerson, "A Stratification of Lao Tzu", Journal of Chinese Religions, Volume 23, Fall 1995, pp. 1-28. (www.idiocentrism.com/china.strata.htm) The history of the DDJ My division of the DDJ and my definition of an early Dao layer only make sense in terms of a theory of the history of the DDJ and of the Daoist school. Because the decimation of sources and the normalization of the surviving sources by Han dynasty editors, this theory must of necessity be reconstructive and somewhat conjectural, but the same is true any other theory. In sum, it is my theory that starting about 350 BC the early Daoists made a break with the political world and court life of their time. (This break with court life has been credited to Yang Zhu, a very shadowy figure, and to men who were described as followers of Yang Zhu). The participants in early Daoism probably included former or present courtiers (astrologers, archivists, and ritualists) as well as fangshi ** (alchemist-like or shaman-like healers -- men and women of power who were in communication with the unseen). These early Daoists developed meditational practices and yoga-like practices of physical cultivation -- the “Nei Ye” chapter in Guanzi is thought to represent their practices rather more concretely than does the DDJ. It is my hypothesis that the 27 chapters I have translated here consist mostly of the hymns and meditation texts of this group but also include three chapters (chapters 13, 30, 31) which stem from the initial break with court life. The separation from court life may never have been total -even in this early Dao you find passages which assume that its hearers are in some way connected with the royal service or even the military. As time went on, in any case, the various courts began to recruit the wise and powerful Daoists into their service, while at the same time members of the group started taking advantage of opportunities for public office, and the later chapters of the DDJ concern themselves extensively with problems of government. A dynamic something like this has been in effect all through Chinese history, and few monastic groups or individual recluses were ever entirely disengaged from the state power. When the Daoist grou (or individual Daoists) became more publicly active they participated in the Hundred Schools debates of the Warring States era, whether at the Jixia academy in Qin, at the court of Hui Liang Wang (King Hui of Wei), or elsewhere. (There are reasons to suspect that part of the DDJ developed in the southern state of Chu and includes material from non-Zhou traditions). In the course of these debates the DDJ picked up terminology and themes from other “persuaders” of the era: Sunzi, Shen Dao, Shen Buhai, the School of Names, the Mohists, the Confucians, the Legalists, and so on. This should be thought of in terms of dialogue and debate, however, or as the appropriation, adaptation, and transformation of themes, and not as the DDJ’s reception of “influences” from the Legalists, Confucians, Mohists, et al For example, the term wuwei was used by most of the thinkers of the time, but it is a contested or “generic” concept -- every thinker used the term in his own way, which usually contrasted with the ways the other thinkers used the term. The transmission of the DDJ was probably both oral and written. Oral recitation is not merely a stopgap method for reaching illiterates, but is in some respects a superior way of transmitting and experiencing a text, and even the literate probably first encountered the text in chanted and memorized form. Oral transmission can be held responsible for many of the variant forms taken by DDJ chapters, though constant re-editing (and maybe even outright rewriting) are also part of the story. However, while Daoists didn’t seem to have been fussy about the exact written form of the text the way Confucians were, there must have been some authority for what was included in the text and what was not, because everything in the GD bundles A and B an be matched with something in the traditional DDJ, and the two or three non-matching passages tacked on to the end of bundle C may not have been intended as part of the DDJ at all. The GD text, according to my reading of the DDJ, includes passages from all groupings within the present DDJ except three. It does not include anything from chapters 67-81, which I surmise were the last ones added; it does not include any of the passages which seem to have some connection to Shen Dao (chapters 23, 27, 49, 60, and 62); and it does not include any of the key passages where the Sage stands alone, outside the formula “Therefore the Sage....” (in chapters 5, 18, 28, 49, 60, and 67-**81). Over the decades paragraphs were gathered stage by stage into chapters, often with chapter-ending tags of various sorts, until around 275 BC the existing chapters and paragraphs were gathered into a single 5000-word+ sequence. Only somewhat latter was this text was divided into exactly 81 chapters, and while some of the 81 chapters are matched exactly in the GD text, eight of the Guodian passages are fragmentary from the point of view of the traditional text, and it is reasonable to suspect that some of the 81 chapters are not really chapters at all, but just groupings of loosely-related or entirely unrelated sayings. (Even chapters 35 and 56, included in the GD text, seem to be composites). Finally, even after the 81-chapter text had established a defined corpus with a prescribed sequence, the tinkering and editing continued. The final outcome was so discontinuous that it has been suggested that either the collection was slapped together entirely at random right at the beginning, or else that an originallycoherent text was physically garbled at some point during transmission. In my opinion, however, the sequence of the DDJ is intelligible when you consider the context and the editor’s (or editors’) purposes. Someone reading through the DDJ in its traditional sequence will repeatedly experience both discontinuities and recapitulations. Sometimes when you move from one passage to the next, even within a single chapter, there is so little apparent continuity that you are forced to ask yourself “What does this have to do with that?” At other times you might find yourself asking, “Haven’t I heard this somewhere before?” The DDJ might be compared to a stew of blended flavors: the present sequence deliberately keeps the hearer off balance by mixing things up while at the same time stitching the whole thing together with reiterated themes. And if the DDJ is first experienced in chanted form, these effects are especially vivid. The DDJ does not want to be easily understood. The relationships between the various levels of the DDJ -the Early Dao, the Sage Dao, and the Final Dao -- are not obvious, but the relationships are real. ** The present order of passages forces the hearer to try to find the interrelationships and the unity of the text, but without making it easy for him or her. The editor did not want the text to separate into layers from which readers could pick and choose their favorites. In this sense, I am the anti-editor of the DDJ, unediting it by undoing the real editor’s work. My translation The DDJ has been translated into English over 200 times. This is testimony not only to the intrinsic general interest of this dense and allusive text, but also to a special interest. In some way it satisfies a critical present-day need. Every translation is motivated to some extent by dissatisfaction with earlier translations, but at the same time, every translation repeats the same solutions and half-solutions to the same problems, and all translators face the same dilemmas: Literal translation, or paraphrase? An exact translation at the price of clumsiness, or an eloquent translation at the cost of inaccuracy? Transliterations, translations, or paraphrases? I tend toward the literal end of the spectrum, partly because I want my translation to be usable by those who can read Chinese. I’ve come up with a few translation solutions which I haven’t seen elsewhere (though I’ve only read about 20 of the 200 translations), and I’ve made a few original interpretations of the Chinese text, but my translation itself probably isn’t original enough to merit publication. The translation is meant yo be the starting point for my presentation of my reading of the book. Dao is translated “Dao”, wuwei and wei are translated “wuwei” and “wei”. These are now English words, more or less, which I have defined in the notes. De has been translated “virtue” because none of the other translation equivalents seem to work, and because De somehow does not seem to be convertible into a proper English word. “Virtue” has been defined in the glossary too, and hopefully readers will eventually come to accept De * as one of various meanings of the English word “Virtue” -- along with chastity, obedience to the categorical imperative, and the virtus of the Renaissance and the classical age. ****Besides trying to isolate the early Dao, I have done two things in this translation which aren’t always done. First, I have paid considerable attention to puns and places where more than one reading of a line can be regarded as valid. Second, the way that DDJ was assembled, the same themes appear over and over again, often in widely separated places -- sometimes in exactly the same words, and sometimes using entirely different language, so I have extensively cross-referenced the key themes and the key terms, and where it seems useful I have also noted themes shared by the DDJ and other works of that and earlier times. My text The text I have used for my translation is not really a critical text as that term is usually used. I have merely have tried to put together the best possible compromise text, a usable, readable composite text based on all available texts, while at the same time noting the tricky passages and the most interesting variants. My work was constrained by the texts available and by what I know about the Chinese language, but my criteria were not philological but literary and philosophical. Is this what was really meant? Does it get the ideas across? How well does this read? In any case, I’m not sure that the Ur-Daodejing is recoverable. The Ur-DDJ could only be the first compilation that included all of the material of the present DDJ, and as I understand things, this text was put together somewhere around 275 BC. But that text was just a compilation of already-existing, widely-circulated materials, and multiple variant forms of various passages were still current when the long version was assembled. There was no way to keep these existing variants from reentering the canonical text – and also no way to keep new variants from being invented. All of texts of the DDJ that we now have show signs of extensive later tampering and tinkering (which, ironically enough, were often motivated by the hope of establishing the UrDDJ), and the newly-discovered MWD and GD texts have raised more questions than they have answered. The DDJ corpus is a braided stream of thoroughly churned texts, and without many more archeological discoveries I don’t think that we’ll get much closer to the Ur-DDJ than we already are. Thus, the criteria for text-editing might as well be qualitative. It is by no means certain that “later” means “worse” or “adulterated”. If you compare the GD and MWD to other texts which are presumably later in origin, many of the seemingly-new passages seem like improvements. I made a large number of choices silently and without comment, and if a choice did not affect the meaning or the style I did not worry about it much. I generally kept particles rather than leaving them out, and in most cases I kept lines found in some editions but not others. In the case of phonetic borrowings, purely graphic variants, and taboo synonym-substitutes, I normally chose the more common form, and I ignored rare variants which I found unintelligible. I generally tried for consistency of vocabulary across the text and usually favored parallel constructions. The exceptions are the cases when I thought that variants might conceal a pun or a nuance of meaning, or when two or more different readings both seemed plausible and interesting. At one point I intended to show my sources in detail, line by line, but given my methodology, there really is little reason to do so. I usually started out by comparing Henricks’ Guodian text (GD) and Lau’s Mawangdui and Wang Bi texts (MWD, WB). Sometimes I checked against Ryden’s GD and Henricks’ MWD, and then finally would take a look at the variants in Jiang Xichang and Ma Xulun. My hope has been to produce a readable text which avoids sidetracking the reader with unimportant questions while highlighting the real problems that remain. Bibliography Jacob Black-Michaud, Cohesive Force, Blackwell, 1975. Stephen Bokencamp, Early Daoist Scriptures, Columbia, 1999. Suzanne Cahill, Transcendence and Divine Passion, Stanford, 1993. Aloysius Chang, "A Comparative Study of Yang Chu and the Chapter on Yang Chu", Chinese Culture, Taipei; Part I, vol. 12, #4, 1971, pp. 49- 69; Part II, vol. 13, #1, 1972, pp. 44-84 Ellen Marie Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Paragon, 1989. Ch’en Ku-ying (Chen Guying), tr. Ames and Young, Lao Tzu: Text, Notes, And Comments, CMC, 1981. A. Conrady, “Zu Lao-Tze cap. 6”, Asia Major (first Series), Vol. 7, 1836, pp. 150-6. Arthur Cooper, The Creation of the Chinese Script, China Society Occasional Papers, #20, 1978, London. W.A.C.H. Dobson, The Language of the Book of Songs, Toronto, 1966. (Dobson) *J. Duyvendak, tr., The Book of Lord Shang Yang, Chinese Materials Center, 1974. John Emerson, "A Stratification of Lao Tzu", Journal of Chinese Religions, Volume 23, Fall 1995, pp. 1-28. (www.idiocentrism.com/china.strata.htm) John Emerson haquelebac John Emerson, “Yang Chu’s Discovery of the Body”, Philosophy East and West, Volume 46-4, October 1996, pp. 533-566: http://www.idiocentrism.com/china.yangchu.htm John Emerson, “Yang Chu in the History of Chinese Philosophy”, unpublished: http://www.idiocentrism.com/china.yanghist.htm Emerson, John, "The Highest Virtue Is Like the Valley", Taoist Resources, Vol. 3 #2, May 1992, pp. 47-62. *URL www.idiocentrism.com/ Morton Fried, The Evolution of Political Society, McGraw Hill, 1967. Gao Dingyi, Laozi Daodejing Yanjiu, Beijing 1999. A.C. Graham, Disputers of the Tao, Open Court, 1989. Robert Henricks, Lao Tzu: The Te Tao Ching, Ballantine, 1989 (MWD). Robert Henricks, Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching, Columbia, 2000 (GD). Philip Ivanhoe, The Daodejing of Laozi, Hackett, 2002. Jiang Xichang, *Laozi jiao gu, Taibei, 1958. Bernhard Karlgren Grammata Stockholm, 1957 (K). Serica Recensa, BMFEA, Russell Kirkland, Taoism, Routledge, 2004. Lafargue, Michael, The Tao of the Tao Te Ching, SUNY, 1992 (especially “A reasoned approach to interpreting the Tao Te Ching”, pp.189-213.). D. C. Lau, Tao Te Ching, Chinese U. Press, Hong Kong, 1982. Mark Edward Lewis, Sanctioned Violence in Early China, SUNY, 1989. Bruce Lincoln, “Banquets and Brawls” in Discourse and the Construction of Society, Oxford, 1992. Ling Shun-sheng, “Chung-kuo tzu-miao te ch’i-yuan”, two articles in Min-tso-hsue yen-chiu-suo chi-k’an, Taipei, 1959. Richard John Lynn, The Classic of the Way and Virtue, Columbia, 1999. Rodney Needham, Right and Left, Chicago, 1978. Ma Xulun, *Laozi Jiaogu, Beijing, 1974. Victor Mair, Tao Te Ching, Bantam, 1990. David Nivison, “Royal ‘Virtue’ in Shang Oracle Inscriptions”, Early China, vol. 4, 1978-9, pp. 52-5. Bill Porter (Red Pine), Laotzu’s Taoteching, Mercury House, 1996. Harold Roth, Original Dao, Columbia, 1999. Edmund Ryden, “Edition of the Bamboo-slip Laozi” in Sarah Allan and Crispin Williams, The Guodian Laozi, SSEC and IEAS, 2000. Edmund Ryden, Daodejing, Oxford World Classics, 2008. Edward Schafer, The Divine Woman, California, 1973. Laurence Schneider, Madman of Ch'u, California, 1986. Axel Schuessler, Minimal Old Chinese and Later Han Chinese, Hawai’i, 2009. (S) Axel Schuessler A Dictionary of Early Zhou Chinese, Hawai’i, 1987. (EZC) Axel Schuessler, ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese, Hawai’i, 2007. (EDOC) Rudolph Wagner, A Chinese Reading of the Daodejing, SUNY, 2003. Arthur Waley, The Way and its Power, Grove, 1958. Wang Li, Gu Hanyu Zidian, Zhonghua Shuju, 2000. (Wang) *Burton Watson, tr., Tso Chuan, Columbia, 1992. Yan Lingfeng, Daojia Sizi Xinbian, Xueshang Shuju, 1968.