2_Davidson_Charlotte - Ideals - University of Illinois at Urbana

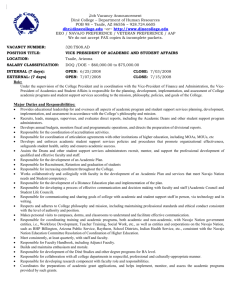

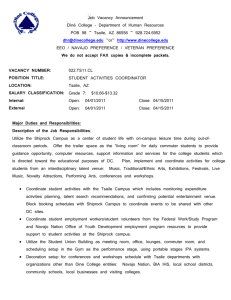

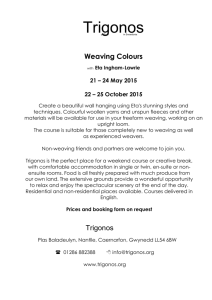

advertisement