Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol

advertisement

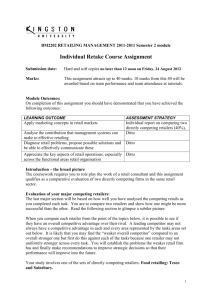

Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 Supply Chain Implications of Customer-Centric Merchandising Strategy Rahul Tyagi Associate Partner, IBM _______________________________________________ Key Words Customer-centricity, merchandising, assortment planning, supply chain, space planning, planogram, logistics, retail strategy Abstract With retailers looking to adopt a customer-centric strategy to succeed in the hyper-competitive environment, it is vital to understand the impact of such a strategy on a retailer’s business functions. While the impact on merchandising is well understood in terms of sharper assortment and improved presentation, the impact on supply chain needs to be studied in detail. This would ensure the alignment of customer-centricity with the organization’s overall direction and growth of revenues and profitability while increasing customer satisfaction levels. _____________________________________ Introduction With the rapidly changing customer demographic, retailers have realized the need to cater to the tastes and preferences of the segments of the population which were earlier lost in the generalization of standard merchandising practices. In addition, because of channel-blurring, the retail space has become so hyper-competitive that a retailer has to differentiate in order to ensure longevity. Such differentiation strategies are manifesting themselves either through the adoption of a value strategy where the focus is on giving best value to the customer or through a services & offerings strategy where the focus is more on providing value-added services & a better offering to the customer to enhance the shopping experience. Most of the extant retail merchandising practices are partial towards planning at a retail chain or a geographic division level ignoring the impact of variations in demographics across stores within a division. Such strategies also tend to diffuse the impact of the retailer’s professed go-to-market strategy leading to incongruence between the strategic and the operational goal. What customer-centric strategy entails Customer-centric merchandising calls for the study of consumer buying trends at a store-level and then grouping the stores based on similarity of consumer behaviour. Thus, one would end up with a finite number of store clusters with each cluster exhibiting some commonality in consumer buying patterns. The sales data of the stores coupled with market basket analytics would also reflect the consumer buying trends. 1 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 Subsequent to obtaining clusters, the assortment and space planning process would be carried out at cluster level. This would be a true customer-centric merchandising as the planning processes become aligned to the customer’s preferences and tastes. However, this raises the prospect of having as many different assortments as there are store clusters. Thus, a retailer would move from a planning process where there was a standard assortment across the entire chain or a division to one where there are as many assortments as there are store clusters. This process change has significant supply chain implications. It is likely that for an individual store the number of items in its assortment may come down yet at the same time the total number of items across all assortments may go up. It is also likely that a distribution centre which was supplying a standard assortment of items to all stores attached to it may have to supply different set of items to different stores belonging to different store clusters and may have to carry a larger set of items. The level of process change at a warehouse would be dictated by: 1. The number of different clusters to which the stores it services belong to: The higher this number, the larger will be the assortment of items which the warehouse has to carry. Increased assortment for same or slightly higher volumes is likely to increase operational costs. 2. The configuration of the warehouse: A modern warehouse with dynamic slot allocations capable of having flexible size bins can more easily accommodate a larger assortment and a lower average volume per item. One possibility may be to re-assign stores to distribution centres to ensure that stores in the same cluster are serviced by the same distribution centre. However, this may not always be feasible as clusters may have stores which are geographically dispersed and re-alignment with a warehouse may incur higher transportation costs and lead times. A more achievable goal is to minimize the number of clusters serviced by a warehouse. This may call for a re-look at the retailer’s distribution strategy. It may merit evaluating a multi-level distribution strategy where key warehouses service RDCs (Regional Distribution Centres) which in turn service much smaller local DCs or store fulfilment centres. An RDC can be serviced by more than one warehouse and a local DC can be serviced by multiple RDCs. Cluster-level assortment planning may also have an implication on how the merchandise is moved to the store from the DC. A good practice is to classify items both by their velocity out of DC and by the number of stores serviced by the warehouse that carries that item. Table 1 is a case in point where transportation strategies are evaluated in the light of ‘Velocity of an item through DC’ and ‘Number of stores that carry that item’. Cost-benefit analysis of a customer-centric merchandising strategy It would be almost tautological to state that to best serve the customer, it is important to tailor the store assortment to the needs and wants of the customer. However, in doing so retailers face the trade-off between increased supply chain costs and the right level of 2 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 assortment customization. An approach is presented here which can help retailers and CPG companies to better evaluate micro-merchandising decisions in the light of supply chain implications. This will also help retailers identify the optimal level of micromerchandising. At an overall level, the supply chain costs will start going up as the retailer decides to move from a chain-wide planning to store-cluster level planning. However, the increase will not be significant initially where the number of clusters is limited. As the number of clusters approaches the number of stores there will be an inflection point where the incremental benefits of micro-merchandising will be offset by increase in supply chain costs required to support such a program. To better understand the costbenefit trade-off of micro-merchandising we will have to look at the various components which define the cost-benefit equation. Key benefit elements Some of the key benefits arising out of micro-merchandising are: 1. Increased sales: Since the assortment is more in line with the clientele visiting the store, hence, the most likely outcome of such an initiative would be an increase in the total sales for the store. 2. Increased profits: A store with merchandise tailored to the customer needs is likely to increase the satisfaction levels of the shoppers. Higher levels of customer satisfaction can be used to drive better pricing by the retailer as the customers would be willing to pay more in return for a better selection. 3. Effective new product introductions: Introducing a new product today is like shooting in the dark and the retailers have to assess early sales patterns to judge where the products would do well and which stores to pull the products out of. By matching the characteristics of store-clusters with the attributes of a new product, retailers can choose the relevant clusters to launch the product in. 4. Reduced lost sales & cost of carrying inventory: One of the problems of a using a standardized assortment is that the store shelf will have relatively less space for items which are sought after by the customers and relatively more space for less wanted items. As a result, the store often ends up with empty shelves for the former and little movement for the latter. This translates to lost sales for the popular item and high inventory holding cost for the less desired items. Tailored assortments do away with both these issues as not only are the items prioritized based on the customer preferences but space allocation on shelf is also guided by the principle of salability for that store or cluster. 5. Alignment of pricing and promotions: Most retailers carry out pricing and promotions for groups of stores. If this grouping can be aligned to the storeclusters which are obtained during the process of customer-centric merchandising, then it is possible to tie the processes of assortment planning, pricing and promotions together. Since the basis of micro-merchandising is similarity in consumer behavior, the same basis would serve as an excellent 3 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 6. proxy for price & promotions groups as well. After accounting for logistical impacts of carrying out assortment planning, pricing and promotions planning for the same store-cluster one can align these processes leading to savings in labor costs and operational synergies for the merchandisers and category managers. Reduced Markdown and promotional expenses: A customer-driven merchandising strategy would ensure higher sell-through. This would hold very true in case of seasonal & fungible merchandise where the value of inventory goes down with time. A better understanding of the store-cluster level customer would enable a better match between the products and the clientele leading to less end-of-season merchandise which effectively translates into lower markdown costs associates with liquidating excess stocks. Key Cost Elements Having outlined the merits of a customer-centric strategy, one needs to delve into the costs associated with such a strategy to enable an accurate estimation of the net benefit that may accrue if a retailer chooses to deploy the aforementioned strategy. The costs can be summarized under a few broad headings like: a. Process costs: Moving from a standardized assortment for a chain to a cluster level assortment plan would entail increased demand on the time of the merchandisers and category managers. One option is to automate the process by correlating product attributes with the cluster’s demographic attributes to enable a better product prioritization. This would enable the retailer to identify the key product attributes which are important for the customers in that store-cluster. If that is achievable then the business user participation can be limited to assortment review and the formulation of business rules based upon merchandising objectives for the cluster. The latter would be a one-time exercise with periodic revisits to amend or append the rule set based upon changes in the business clime in the intervening period. b. Supply chain costs: This more measurable and visible part of the cost increase would arise out of planning for the replenishment for a different set of items for different store-clusters. The execution would also entail cost increases owing to impact on warehousing and logistics processes. To get a better grasp on the impact on supply chain costs, it is imperative that one tries to understand the various components of supply chain processes that are impacted. Below are some of the key areas which will see a change in cost structure owing to the adoption of a customer-centric merchandising strategy: 1. Planning & ordering costs: The cluster assortments have a limited amount of assortment overlap and the summation of various cluster-level assortments would increase the total number of items for the chain. As a result a. The warehouse planning and ordering costs will increase: Not only will warehouses have to plan for additional items but there is likely to be an increase in the number of orders leading to a cost increase. This is so because a warehouse may span multiple store-clusters, hence, multiple assortments with a broader range of item velocity. 4 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 b. Store’s planning & ordering costs will decrease: Stores will have to plan for fewer items and their ordering frequency will decrease leading to a lower ordering cost. The latter will be a result of aligning shelf space with customer preferences leading to more space being allocated to popular items and therefore infrequent stock-outs of those items and longer shelf replenishment cycles. As the stores’ planning and ordering costs are significantly higher than the warehouses’ costs for planning & ordering, hence, this would lead to a cost savings as the same degree of impact yields a larger quantum of cost change at store level as compared to a warehouse. 2. Store operations cost: Stores will have fewer items to deal with. Shelf stocking costs are likely to come down as more space is allocated to popular items leading to lower replenishment frequency. Labor costs can also be saved if item shelving rules like “case and a quarter” or case-plus can be adopted to enable case shelving. This would do away with the costs associated with breaking a case before shelving. 3. Inventory costs: There would be profound impact on inventory costs. Warehouse will now have to stock many more SKUs with a broader range of item velocity as compared to earlier and not all SKUs will be supplied to all stores. This will increase the inventory holding costs at the warehouse. Stores will see the positive side of inventory impact as many slower items are eliminated leading not only to freeing up valuable shelf space but also reducing holding costs. Owing to the high velocity of the remaining items in the assortment and the reduction in the average time an item spends on the shelf, there is likely to be a positive margin impact. Overall, the inventory costs are likely to come down as the positive cost impact at the store offsets the cost increase at the warehouse. 4. Warehousing & logistics cost: Increase in the number of items to be stocked at the warehouse entails an increase in the number of stocking & picking area assignments. Space will have to be carved out for the increased number of SKUs and since many of these items may have less movement, allocating bins will become an issue. The shelving costs will also increase with an increase in the number of bins and shelving areas in the warehouse. One standard best practice followed by many retailers is to divide the warehouse into different zones depending upon the type of items. Under such an arrangement, a “flex-area” is dedicated to seasonal and low-volume/high-velocity items. Picking in such areas may require specialized equipment like pick-to-light, robotic picking systems and automated sortation equipment which enables less-than-case picks. Overall, picking costs are likely to increase as pick routes become longer. Flow path redesign can be resorted to in extreme conditions if picking costs increase beyond expectations. Modern warehousing practices like AS/RS (Automated Storage & Retrieval System), dynamic slotting and interleaved picking can substantially mitigate the impact of SKU proliferation. The latter two practices have been found especially effective in cases where the number of items is large and pick volumes vary widely across products and time. 5 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 Logistics costs in terms of transportation costs are likely to go up as well. The increase in costs will be felt on both the inbound and outbound sides of the warehouse. Inbound costs will increase because there will be many SKUs with smaller volumes (owing to limited number of stores carrying them) which will require LTL or shipment consolidations. Both involve costs in terms of money or time. Handling increased number of SKUs at warehouse inbound will increase receiving costs and QC costs as well. On the outbound side, there will be two countering influences. For each store a potential reduction in the number of overall items and slow movers would increase shipment efficiency. More pallet level & case level shipments can be planned leading to reduction in handling and shipping costs. However, owing to the variation in the assortment across stores, route planning will become complicated. Route plans will have to be generated at multiple levels considering factors like common set of items, unique items per store in stores on a common route, their replenishment frequency, loading restrictions and consolidation opportunities. This is likely to lead to a polarization in shipment strategies to stores. Unlike earlier when most shipments were mixed and multi-store, in the new scheme of things there will be more dedicated shipments to a store and fewer across store shipments. Of course, this has to be viewed keeping in mind the replenishment frequencies of the common items carried by stores along a common route and those of the unique items. At an overall level, though, the outbound costs are most likely to go up. a. DSD item supply chain: One key pre-requisite for stores that are being confined to a cluster is that they should be capable of receiving the items that are assigned to them by the store-cluster level assortment. This issue is exacerbated for DSD items as most DSD vendors have limited geographical reach and if the cluster is geographically dispersed, then one would need to create source of supply for the DSD items. This is a reason why lot of retailers look at supply constraints before embarking on a customer-centric merchandising initiative. There are many qualitative factors that need to be taken into consideration. If the item is a key item in the assortment, then the retailer would want to take control of the supply chain of the item. On the other hand, if the item is a high-cost item with infrequent sales, then it is best handled by the DSD supplier as that would remove the logistics hassles from retailer’s consideration. Perishability is an important determinant of making decision about going DSD for an item. Since freshness is of paramount importance in such cases, one would want the item to be directly supplied to the store rather than spending a part of replenishment lead time in the warehouse. Moving to DSD is likely to increase the costs for an item as the vendor will take on the logistics responsibility from the retailer and would expect to be defrayed for this additional service. This premium is usually built into DSD pricing. Thus, one can see that there are many supply chain functions which are accretive to the benefits of a customer-centric merchandising strategy and there are certain which add to the costs of such an initiative. Please refer Appendix for more details. Strategic Factors in Decision-Making 6 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 In addition, retailers need to evaluate their customer-centric merchandising decisions in the light of two major factors: Their positioning in the market: Value players will have difficulty in raising prices to absorb the cost impact whereas service-oriented retailer may be able to play the market-focused assortment card quite well and counter any cost increases with a perceived better offering. A customer-centric strategy may reduce dependence on promotions facilitating a transition from a Hi-Lo pricing to a more EDLP (Every Day Low Pricing) strategy. An EDLP strategy greatly simplifies the pricing structure and the associated costs and is becoming increasingly popular in the grocery retail industry. Supply chain strategy: It may merit evaluating outsourcing options in warehousing and transportation on a selective basis. The basis can be a choice of products and stores which are leading to large increase in supply chain costs. Simulation can be used to determine average supply chain cost per item-store in a cluster. Items & stores that seem to be having costs consistently above the average can then be evaluated for alternate fulfillment models. Some of the commonly employed models would be: 3PL: Retailer may want to look separately at warehousing and transportation costs and then decide which portions of the supply chain to outsource. There are specialized LTL service providers & supplier shipment consolidators who can take over the required functions and easily integrate with the retailer’s supply chain DSD: Always a good option if there are local suppliers available for the item-store combination. Cost comparison needs to be done with other supply options before deciding to go with DSD. Supply from another store: A good practice if the retailer has a large store with a big backroom and when the cost of holding inventory in the store’s backroom is not that high. This would just add another level to the transportation network and would optimize the load factor as multiple smaller runs are possible between stores with a limited cost increase. One can derive a heuristics which can help in formulating the micromerchandising strategy from a supply chain point-of-view. This is illustrated as a toolkit at the end of this article. In conclusion, it is imperative in the current retailing environment for retailers to formulate a well-defined customer-centric merchandising strategy. Yet in the course of operationalizing such a strategy one needs to look at the impact it may have on various supply chain elements like warehousing, transportation, replenishment and store operations. It is then that the true cost-benefit of a micromerchandising strategy can be explored and the right level of micro-merchandising ascertained. Without this due diligence a retailer may end up increasing the overall operational costs of such an initiative which may have repercussions on the bottom-line. For retail segments like grocery which survive on wafer-thin margins this impact can be fatal. There are plenty of examples in the industry where a half-baked customer-centric merchandising strategy was put in place only to be hastily recanted owing to the disproportionate rise in supply chain costs leading to bleeding of overall margins. 7 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 However, a well-conceived customer-focused merchandising strategy which marries the benefits of increased customer-led assortment with the associated costs of achieving that would not only ensure a higher level of customer satisfaction but would also lead to a veritable increase in margins and cost containment. Appendix: Micro-Merchandising Toolkit 1. Identify the basis for customer-centric merchandising. Since the general notion is to make assortment more customer-centric, one would attempt to cluster stores on the basis of factors that indicate customer behavior. These can be demographics & geography related factors. POS information can, by reflection (assuming sales represent customer interests), also be used to group stores. 2. Identify any constraints for the customer-centric store grouping process. These constraints can be source of supply driven or regulatory (E.g. liquor, tobacco) 3. Evaluate the cost-benefit equation for the most granular level of store clustering. This can be done using simulation with the various cost-benefit elements as outlined below. General Factors Impact Factor Sales Gross Profit New Product Introduction Costs Lost Sales Type of Impact Increase Notes Shelf Item Sales(new state) - Shelf Item Sales(old) Shelf item sales under the new state can be taken as (total shelf area) * (popular item sales-old state) / (area allocated to popular items-old state) Increase Profit from shelf(new) – Profit from shelf (Average item (old) sales velocity Average margin of shelf = ∑(Item sales increases, velocity)*(Item margin) average margin may increase) Decrease (The New products launched only in store chances of clusters where the probability of success success will go is high. This can be achieved by up) matching the characteristics of a storecluster with item attributes and identifying which are the key purchase determinant item attributes. Decrease Popular items get more shelf space owing to elimination of slow movers. A good proxy for lost sales reduction will be: Average Inventory on Shelf of popular items / Sales velocity of popular items This would go up in customer-led merchandising which implies less lost sales 8 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 Supply Chain Factors Impact Factor Type of Impact Ordering/Planni Decrease (Store ng Costs cost decrease would more than offset warehouse cost increase) Notes Ordering costs are proportional to: Line items in order * Order frequency Warehouse: Increase in number of items and most likely order frequency implies cost increase. Store: Reduction in number of items and order frequency implies cost increase Store Operations Decrease More shelf space to popular items means Cost that re-stocking frequency decreases. Also, full case packs can be stocked on shelf rather than part-cases. Both imply labor cost savings. Inventory Costs Decreases. Store Warehouse: Increase in item variety and cost decrease increase in complexity of replenishment offsets & fulfillment frequencies implies cost warehouse cost increase. increase Store: Reduction in slow mover implies cost savings. A good proxy for inventory savings is: ∆ (Average Sales velocity of shelf) * Cost Complement i.e. average factor to covert retail price to cost. Sales velocity increases which implies inventory cost decrease. Warehousing & Increase Warehouse: Stocking & picking costs Logistics Costs increase and so do receiving costs. Logistics: Cost per mile per unit weight/volume goes up as route planning becomes complex for both inbound and outbound and LTL increases. To get a quantitative value for the change in costs supply chain simulation will have to be done. This can be achieved using popular tools like eSCOR or simulation languages like ARENA. 4. After one has computed the net cost-benefit impact at the most granular level of customer-centric merchandising which is likely to be store-specific assortments, one need to start clustering stores based on the chosen basis of micromerchandising. 5. Compute the cost-benefit equation for each level of store clustering. 6. Ideally, one should be able to come up with a graph of net benefit and level of store clustering. (Figure 1) That graph can be used to identify the right level of 9 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 store clustering which aligns with the retailer’s customer-centric merchandising strategy. 10 Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 Tables & Graphs Table 1: How to decide logistics strategy for an item High Velocity Through DC More frequent shipments to the “carrying” stores; Impact area: Route Planning No significant impact on shipping costs Higher shipment frequency Opportunity for load consolidations (LTLs to TLs); Shipping cost savings possible LTL/parcel shipping is the plausible option Shipping costs likely to increase Good candidates for DSD (Direct to Store Delivery) Evaluate load consolidation opportunities to convert LTL to TL Shipping costs likely to increase DSD can be a viable option (needs to be evaluated) Low Low Number of stores carrying that item 11 High Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) Vol. 2 Issue 2 April 2008 Figure 1: Value Equation of Customer-Centric Merchandising Net Benefit StoreSpecific Level of Store Clustering 12 ChainWide