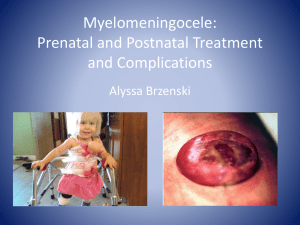

Human Sentience Before Birth

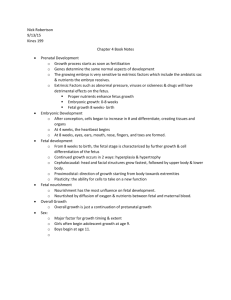

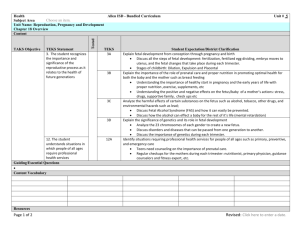

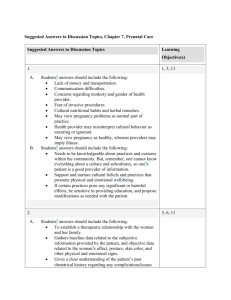

advertisement