PREDICTING CONSUMER INTENTIONS TO PURCHASE GREEN

PREDICTING CONSUMER INTENTIONS TO PURCHASE GREEN

CARS: AN EMPIRICAL TEST OF COMPETING THEORIES

Dr. Chi-Horng Liao, Ta-Hwa Institute of Technology, Taiwan lchjerry@thit.edu.tw

ABSTRACT

The aim of this research is to find the key factors that would influence customer purchasing intentions for green cars. There is an increasing awareness that many of environmental problems are caused by human economic activities. For this reason, it is important to find and use a suitable model. “Theory of Planning Behavior (TPB)” was proposed by Ajzen in

1985 and is a famous and popular model to measure customers purchasing behavior intentions. Therefore, the researcher combined with other related aspects for the questionnaires. The rest of the research is organized as follows: The researches explore the

TPB model and other related aspects by literatures in Section 2. Analyzing the past researches give us better picture on the behavior of the customer toward green cars. In the subsequent sections of the paper, the researcher focuses the expansion of research model. In

Section 3 the existing approaches and relate to suitable aspects with TPB model would be discuss. The hypothesized models will be empirically test using the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, supported by LISREL 8.8 software with maximum likelihood estimation.

Key words : Theory of Planning Behavior, Green Cars, Structure Equation Modeling

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing awareness that many of environmental problems are caused by human economic activities. The activities not only consume huge amounts of resources, but also lead to the disposal of tons of pollutants into the environment at levels which nature can no longer absorb. This situation generates problems such as climate change, global warming, pollution, loss of biodiversity, and many more. Because of high-prices energy and conscious of environmental protection, green cars play an important role in cars purchasing. In the past research, many scholars focused designs of engines, fuel systems, and etc. The researchers always try to find out the way to decrease pollution. There are few research describing customer behaviors and purchasing needs of green cars. Thus, to find the key factors which would influence green cars buying intention is important.

There are some research pointed out that the primary task is to explore the needs of the customers and apply these needs in the development of green products (Baumann et al., 2002;

Hart, 1995). These researches described that the designers have to consider what customers like and need, and put them together with production of green products. Many influencing factors such as characters of green products, customers satisfy, and customer relationship, were discussed in different research models. In this paper, the researcher tries to find out the purchasing intention of green cars. Turrentine (2001), Marcus (2009) and Ishioka (2009) sited that green cars are important in the green product industry.

The aim of this research is to find the key factors that would influence customer purchasing intentions for green cars. Base from the report, vehicle emissions contribute to the increasing concentration of gases linked to climate change (World Energy Council, 2009). In order of significance, the principal greenhouse gases associated with road transport are carbon dioxide

(CO

2

), methane (CH

4

) and nitrous oxide (N

2

O)(Marianne 2010). Road transport is the third largest source of greenhouse gases emitted in the UK, and accounts for over 20% of total emissions, and 33% in the United States. Of the total greenhouse gas emissions from transport, over 85% are due to CO

2

emissions from road vehicles. The transport sector is the fastest growing source of greenhouse gases (IPCC, 2007).

In order to reduce the greenhouse effect, for this reason, it is important to find and use a suitable model. “Theory of Planning Behavior (TPB)” was proposed by Ajzen in 1985 and is a famous and popular model to measure customers purchasing behavior intentions. Therefore, this research used TPB model to be a basis combined with other related aspects for questionnaires. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. TPB model and other related aspects by literatures is discuss in Section 2. Resorting to collect past researches could let the research model more complete. The development of green cars is discuss within this section.

In the subsequent sections of the paper, we focus on the expansion of research model. In

Section 3 we briefly discuss existing approaches and relate to suitable aspects with TPB model. The data collected by questionnaires will be analyze by the next research. The analysis method includes Principle Component Analysis (PCA), Analysis of Reliability and

Validity, Regression Analysis, and One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). By these results, we could know about the relationships among aspects and the key influencing factors for customers green cars purchasing behavior. The conclusions of this paper would be discussed of the implications of the use of the proposed research model to the manufacturing industry in the final section.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This research discusses the development and the consumer behavior toward green cars.

Afterward, the development history of TPB model would be introduced by many researches.

In the end of this section, we combined some related research with TPB model to built own research model for this study.

Green cars

A green cars or environmentally friendly vehicle is a road motor vehicle that produces less harmful impacts to the environment than comparable conventional internal combustion engine vehicles running on gasoline or diesel, or one that uses alternative fuels (RIC, 2005).

Green cars are powered by alternative fuels and advanced vehicle technologies and include hybrid electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, battery electric vehicles, compressed-air vehicles, hydrogen and fuel-cell vehicles, neat ethanol vehicles, flexible-fuel vehicles, natural gas vehicles, clean diesel vehicles, and some sources also include vehicles using blends of biodiesel and ethanol fuel or gasohol(US department of energy, 2010).

Several author also include conventional motor vehicles with high fuel economy, as they consider that increasing fuel economy is the most cost-effective way to improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions in the transport sector in the short run.

As part of their contribution to sustainable transport, environmentally friendly vehicles reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, and contribute to energy independence by reducing oil imports (Green Student, 2010).

There are some attempts in the literature to define a green product (Elkington et al., 1988;

Schmidheiny, 1992). Some studies focus on designing and marketing green products (Green et al., 1994; Roy, 1999; Vaughan et al., 1993). But it still confuses on what constitutes an environmentally friendly product, for consumers as well as for companies (Welford, 1998).

Thought and needs form customers and companies are not the same, even they could be opposite to each other in some particular situations. Take fuel for example, customers always want characteristics of fuel include cheap and helpful to engine works. But some cheap fuel causes lots of pollution such as air pollution, and there is a duty for each company to maintain environmental protection. Thus, it is hard to get the balance between customers’ needs and company’s duty.

Fortunately, hybrid cars, solar-power cars, and other environmental protection vehicles have been invented in recent years. Not only cars’ properties could be fit for environmental protection laws and terms, but also puts marketing essential factors like fashion into the car

design.

Many past researches focus on designs of engine and fuel systems. There are few researches to try to find the relationships between customers’ needs and characters of green cars. Chang

(2010) proposed a framework named “SEEDS” to describe the relationships amount “Supply

Side”, “Environment Protection Side”, “Economic Side”, “Demand Side”, and “Substitute

Side”. Based on this framework, the author proposed some suggestions for different industries. Lantos et al. (2009) examined the felt need for new products in organizations, the usefulness of the new product development education, and the nature of the new product development discipline, for showing the paper’s analysis of the death of the new product development courses in AACSB-accredited schools.

As the environment continues to worsen, the consumer has begun to realize the seriousness of the problem. Base on the needs of the consumer, businesses should design a green products to match the customers’ demands. This paper could be seen as a pioneer in the research of green car design and customer behavior intention.

The theory of planning behaviors (TPB) model

The Theory of Planned Behavior was developed in response to a related existing model—The

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen, 1988, 1991). Briefly, the Theory of Reasoned

Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) places intention as the principal predictor of behavior. So conceived, the more one intends to engage in behavior, the more likely is the occurrence of the behavior. Determining intention are attitude and subjective norm. The attitudinal determinant of intention is defined as the overall evaluation of behavior.

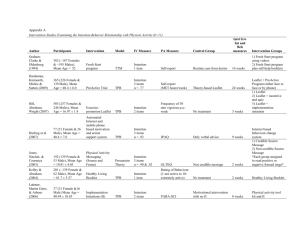

This overall evaluation, in turn, is composed of the salient beliefs: the perceived likelihood of particular consequences of the behavior occurring, weighted by an evaluation of the consequences. The subjective norm determinant of attitude is conceptualized as social pressure from significant others to perform or not perform the behavior. The subjective norm, in turn, is composed of normative beliefs: the perceived pressure from salient referents, weighted by the motivation to comply with the referents. The TRA has received support across a range of contexts (Sheppard, Hartwick, & Warshaw, 1988). A recognized limitation of the TRA is that it was developed to deal with behaviors that are completely under an individual’s volitional control (Ajzen, 1988; Fishbein, 1993). Figure 1 is the structure of

TRA.

Attitude

Behavior Intention Actually Acts

Subject Norm

Figure 1: The structure of TRA.

In response to the aforementioned limitation of the TRA, Ajzen (1988, 1991) proposed an extension—the Theory of Planned Behavior. The TPB was designed to address behaviors not completely under volitional control. The model is identical to the TRA except that a perceived behavioral control construct has been added. Perceived behavioral control relates to the ease or difficulty of performing a behavior. Perceived behavioral control is affected by perceptions of access to necessary skills, resources and opportunities to perform a behavior, weighted by the perceived valence of each factor to facilitate or inhibit the behavior. In the

TPB, perceived behavioral control is viewed as determining intention as well as behavior directly. The TPB has received strong support in predicting a wide range of intentions and behaviors (Godin & Kok, 1996; Sutton, 1998).

To understand the relationship between belief structures and antecedents of intention, several studies have examined approaches to decomposing attitudinal beliefs (Taylor & Todd, 1995;

Chau & Hu, 2002; Chen et al., Jonathan, 2007; Riemenschneider et al.). Moreover, Shimp and Kavas (1984) suggested tha tthe cognitive components of belief would not be organized into a single conceptual or cognitive unit. According to Taylor and Todd (1995), in the TPB model, attitudinal, normative and control beliefs are decomposed into multidimensional belief constructs. The TPB model specified that, based on the diffusion of innovation theory

(Jonathan, 2007), the attitudinal belief has three innovation characteristics that influence behavioral intentions are relative advantage, complexity and compatibility. Green technology can be considered a service innovation (Verhoef & Langerak, 2001). This study thus hypothesizes that the TPB model provides a more satisfactory explanation of behavioral intentions to purchase green cars..

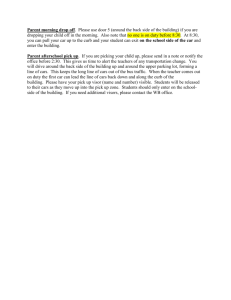

The TPB (Ajzen, 1988 & 1991) extends the TRA (Fishbein, 1993), to account for conditions where individuals do not have complete control over their behavior. The TPB postulates that actual acts is determined by behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control.

Behavioral intention is determined by three factors: attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control. Each factor is in turn generated by a number of beliefs and evaluations.

Attitude

Subject Norm Behavior Intention Actually Acts

Perceived

Behavior Control

Figure 2: The structure of TPB.

“Behavior Intention” means personal volition and the volition would influence customers final decisions. Behavior Intention is impacted by two factors. One is an internal factor named “Attitude”, and the other one is an external factor named “Subject Norm”. “Attitude” is combined “Salient Beliefs (or Behavioral Beliefs)” with “Outcome Evaluation”, and it means the feelings of customers when they try to do the specific thing. It could be good and bad, advantage and disadvantage, interesting and boring, or else (Ajzen, 1985). “Subject

Norm” is combined “Normative Belief” with “Motivation to Comply”, and it means people are under the pressure what they try to do something. The pressure is created by the people’s parents, spouses, children, relatives, religious belief and etc. These individual suggestions would influence the behavior intention.

“Perceived Behavior Control” is combined “Control Belief” with “Perceived Facilitation”, and it means when people try to do something, they would estimate how many the resources and opportunities they have and what kind of predicaments they might face to. “Perceived

Behavior Control” could influence directly “Actually Acts” in some research, and some research shows the relationship between these two aspects is in-directly.

There is no past research using TPB model to measure green cars purchasing behavior intention. Thus, this paper could be the first research to estimate key influencing factors for behavior intention by using TPB model. With results of this paper, researchers could get valuable information from relationships among aspects.

THE RESEARCH STRUCTURE

In this section, we proposed a complete model for measuring influencing factors and green car purchasing behavior intention. We find and collect related research to create the structure.

Based on past research, hypotheses would be proposed in objectivity. Some research results presented “Knowledge” would influence personal attitudes (Butler et al., 1998; Hungerford et

al., 1990; Limayem et al., 2000; Yan et al., 1999). People have different attitudes when they face to the same challenge because no one gets the same history of growing up and schooling.

By these differences, people use own attitude to design what they like or what they want.

Because of this, the hypothesis 1 is proposed as follow:

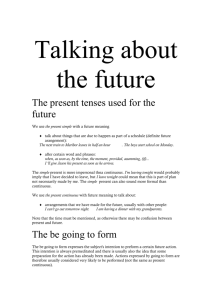

H1: Knowledge will have a significant impact on Attitude.

Clawson and Knetsch (1969) proposed product characteristics were the key factor that would influence customers’ ability of perceived behavior control. Product characteristics include complexity, risks of purchasing, and etc. There is not much literature described relationships between product characteristics and perceived behavior control. Thus, we proposed the hypothesis 2 as follow:

H2: Characteristics of product have a significant impact on Perceived Behavior Control

Because TPB model offers a clearly defined model/structure that allows the investigation of the impact those attitudes, personal and cultural determinants and rational behavior control have on customers’ behavior intention to buy environmental protection products, the model forms the theoretical structure of this study. TPB model was used to measure behavior intention of purchasing green products before (Alwitt et al., 1996; Chan, 2001; East, 1997;

Diamantopoulos et al., 2003; Kalafatis et al., 1999). The hypothesis 3 to hypothesis 5 is described as follow:

H3: Personal Attitudes have a significant impact on Behavior Intention.

Consumers may perceive both difficulties and risk when considering buying green car, they can be expected to use their cognitive resources in forming beliefs toward the related attributes, which in turn may result in the development of an overall feeling (attitude) toward the behavior in question (refer to e.g., Antil, 1983; Zaichkowsky, 1985; Rossiter & Percy,

1987).

H4: Subject Norms have a significant impact on Behavior Intention.

Subjective norm, or the influence of others, has also been found to affect consumers’ willingness to adopt a technology. Taylor and Todd (1995a, 1995b) reported that subjective norm positively affects consumers’ adoption of innovative products. Green (1998) found that normative pressures have a significant positive effect on behavior Intention

H5: Perceived Behavior Control has a significant impact on Behavior Intention.

As the above-mentioned, TPB model is a perfect method to measure the key factors of behavior intention and causal relationships among aspects. The structure of this study is presented in figure 3 as follow. In the next section, we create questionnaires based on this model and past literatures.

H1

Knowledge Attitude

H3

Subject Norm

H4

Behavior Intention

H5

Product

Characteristics

H2 Perceived

Behavior Control

Figure 3. Research Model

RESEARCH METHODOLGY

Data collection

To empirically verify the proposed model, a comprehensive survey was conducted in Taiwan.

Although English was initially used to develop the survey questionnaire, it was subsequently translated into Chinese to facilitate respondents’ understanding. Linguistic equivalence between the English and Chinese versions was ensured by employing the back translation technique (Bhalla & Lin, 1987).

This study adapted the measures used to operationalize the constructs included in the investigated model from relevant previous studies, making minor wording changes to tailor these measures to the context of online shopping. The measures of actual usage, behavioral intention, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use adapted from Davis (1993). The belief items for measuring compatibility, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were revised from Taylor and Todd (1995). Items for interpersonal influence and external influence were adapted from Bhattacherjee (2000), while items for measuring self-efficacy and facilitating conditions were adapted from Taylor and Todd (1995). All items were measured using a seven-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7

= strongly agree).

Data for this study will be collected as part of a larger mail survey of consumer perceptions

about green car purchasing. Participants were adults residing in Taipei, Taichung, and

Hsin-Chu city. A three-page questionnaire was used as the research instrument. With the establishment of content validity, the questionnaire was refined through rigorous pre-testing.

The pretesting focused on instrument clarity, question wording and validity. The pre-tested was performed in an iterative manner among a convenience sample of colleagues, students, and other consumers drawn from the general public. The 32 respondents of this test were asked to provide comments on the relevance and wording of the questionnaire items, length of the survey, and time taken to complete it. Based on the feedback, some of the questionnaire items were dropped. Further, the questionnaire layout was modified, and the wording of some of the questions was changed to improve clarity.

Multiple scale items, that were primarily adapted from Taylor and Todd (1995), were used to elicit respondents’ salient beliefs, normative beliefs, self-efficacy, and attitude and intention towards green car purchasing. The instrument also included measures for assessing the level of green car purchasing and other relevant demographic indicators.

As a pilot test to gauge response rate, an initial mailing was sent to 120 of the randomly chosen sample. The survey package consisted of a cover letter, questionnaire, and pre-paid return envelope. A drawing to win one of NT$100 gift certificates, redeemable at shopping mall, was offered as an incentive to respond. As a reminder, a follow-up post-card was sent to all of the respondents a week after the initial mailing. Sixty one completed questionnaires were returned for a response rate of 56%. At the present time, 900 more survey was sent to the respondents via mail. After the collection of these survey questionnaires, the researcher will proceed to the statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

The next stage, the hypothesized models are empirically tested using the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, supported by LISREL 8.8 software with maximum likelihood estimation. Following the two-stage model-building process for applying SEM, the measurement model was estimated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test reliability and validity of the measurement model, and the structural model also analyzed to examine the model fit results of the proposed theoretical models.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Chi-Horng Liao acknowledge the Taiwan National Science Council for the funding provided under

Research Plan No. NSC 99-2632-E-233-001-MY3.

REFERENCES

1.

Ajzen I (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned, In Kuhl J. & Beckman J.

(Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior, Heidelberg: spronger, pp.11-39.

2.

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior.

Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

3.

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago’ Dorsey Press.

4.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

5.

Alwitt LF, Pitts RE (1996). Predicting purchase intentions for an environmentally sensitive product. J. of Consumer Psychology. 5(1): 49-64.

6.

Alternative Fuels and Advanced Vehicle Data Center, U.S. Department of Energy.

Retrieved from http://www.afdc.energy.gov/afdc/vehicles/index.html.

7.

Antil, J. H. (1983). Conceptualization and operationalization of involvement. Advances in

Consumer Research, 203–209.

8.

Bhalla, G., & Lin, L. (1987). Cross-cultural marketing research: A discussion of equivalence issues and measurement strategies. Psychology & Marketing, 4, 275-285.

9.

Bhattacherjee, A., (2000) Acceptance of e-commerce services: the case of electronic brokerage. IEEE Transaction on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics – Part A: Systems and

Humans 30(4), 411-420

10.

Baumann H, Boons F, Bragd A (2002). Mapping the green product development Field: engineering, policy and business perspectives. J. of Cleaner Production. 10(5): 409-425.

11.

Butler P, Peppard J (1998). Consumer purchasing on the internet: processes and prospects.

European Management Journal. 16(5): 600-610.

12.

Chan YK (2001). Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior.

Psychology and Marketing. 18(4): 389-413.

13.

Chau P.Y.K., Hu , P.J.H. (2002) Investigating healthcare professionals’ decisions to accept telemedicine technology: an empirical test of competing theories, Information and

Management 39 (4) 297–311.

14.

Chang CC (2010). The SEEDS of oil price fluctuations: A management perspective.

African J. of Bus. Manage. 4(7): 1390-1394.

15.

Chen L.D., Gillenson M.L., Sherrell D.L., (2002) Enticing online consumers: an expended technology acceptance perspective, Information and Management 39 (8)

705–719.

16.

Davis, F.D. (1993). User acceptance of information technology: system characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. International Journal of Man Machine Studies

38(3), 475-487.

17.

Diamantopoulos A, Schlegelmilch BB, Sinkovics RR, Bohlen GM (2003). Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. of Business Research. 56(6): 465-480.

18.

East R (1997). Consumer behavior: a advances and applications in marketing.

Prentice-Hall, Hemel Hempstead.

19.

Elkington J, Hailes J (1988). The green consumer guide, Victor Gollancz, London.

20.

Fishbein, M. (1993). Introduction. In D. J. Terry, C. Gallois, & M. McCamish (Eds.), The theory of reasoned action: Its application to AIDS-preventive behavior. Oxford, UK’

Pergamon

21.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA’ Addison-Wesley.

22.

Godin, G., & Kok, G. (1996). The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11, 87–

98.

23.

Green K, McMeekin A, Irwin A (1994), Technological trajectories and R&D for environmental innovation in UK Firms. Futures 26 10. pp. 1047–1059.

24.

Green Student U. Retrieved from http://www.greenstudentu.com/encyclopedia/ green_vehicle_guide.

25.

Hart, SL (1995). A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. of Manage. View. 20(4):

986-1014.

26.

Hungerford HR, Volk TL (1990). Changing learner behavior through environmental education. J. of Environment Education. 21(3): 8-21.

27.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). "IPCC Fourth Assessment Report:

Mitigation of Climate Change, chapter 5, Transport and its Infrastructure" (PDF).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg3/ar4-wg3-chapter5.pdf.

28.

Ishioka M, Yasuda K (2009). Product development concept with product sustainability.

Proc. Manage. of Engineering & Technology. 1699-1706.

29.

Jonathan L. Ramseur (January 18, 2007) (PDF). Climate Change: Action by States To

Address Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Congressional Research Service. p. 16. Retrieved from http://www.climateactionproject.com/docs/crs/80733.pdf.

30.

Kalafatics SP, Pollard M, East R, Tsogas MH (1999). Green marketing and Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior: a cross-market examination. J. of Consumer Marketing. 16(5):

441-460.

31.

Lantos GP, Brady L, McCaskey P (2009). New product development: an overlook but critical course. J. of Product & Brand Manage. 18(6): 425-436.

32.

Limayem M, Khalfa M (2000). Business-to-consumer electronic commerce: a longitudinal study. Proc. of 5 th

IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications. pp.

286-290.

33.

Marcus AA, Fremeth AR (2009). Green management matters regardless. The Acad. Of

Manage. Perspective. 23(3): 17-26.

34.

Marianne Weingroff. "Activity 20 Teacher Guide: Human Activity and Climate Change".

Ucar.edu. Retrieved from http://www.ucar.edu/learn/1_4_2_20t.htm.

35.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Organization for Economic

Co-operation and Development. Working Group on Low-Emission Vehicles (2004). Can cars come clean?. OECD Publishing. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9789264104952. http://books.google.com/?id=Y6s7CDzLz5wC&pg=PA84&dq=%22Green+vehicle%22+l ev#PPA84,M1

36.

R.I.C. Publications (2005). Rainforests. p. 67. ISBN 9781741263305. http://books.google.com/?id=_Ax8ElEN5EcC&pg=PA67&dq=%22Green+vehicle%22

37.

Riemenschneider C.K., Harrison D.A., Mykytyn Jr. P.P., (2003) Understanding it adoption decisions in small business: integrating current theories, Information and

Management 40 (4) 269–285.

38.

Rogers E.M. (1995) , Diffusion of Innovations, Free Press, New York.

39.

Rossiter, J. R., & Percy, L. (1987). Advertising and promotion management. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

40.

Roy R (1999). Designing and marketing greener products: the Hoover case. In: M.

Charter et al. Greener marketing, Greenleaf, Sheffield. pp. 126–142.

41.

Schmidheiny S (1992). Changing course: a global business perspective on development and the environment. Business Council for Sustainable Development. , MIT Press,

Cambridge (MA).

42.

Sheppard, B., Hartwick, J.,&Warshaw, P. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research.

Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 325– 343.

43.

Shimp T., Kavas A., (1984). The theory of reasoned action applied to coupon usage,

Journal of Consumer Research 11 (3) 795–809.

44.

Sutton, S. (1998). Predicting and explaining intentions and behavior: How well are we doing? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 1317– 1338.

45.

Taylor S., Todd P.A., (1995) Understanding information technology usage: a test of competing models, Information Systems Research 6 (2) 144–176.

46.

Turrentine TS, Kurani KS (2001). Marketing clean and efficient vehicles: workshop proceedings. UCD-ITS-RR-01-06 Institute of Transportation Studies, University of

California: Davis, California. March 22-23.

47.

Vaughan D, Mickle C (1993). Environmental profiles of European business,

Earthscan/Royal Institute of International Affairs, London.

48.

Verhoef P.C., F. Langerak, (2001) Possible determinants of consumers’ adoption of

electronic grocery shopping in the Netherlands, Journal of Retailing and Consumer

Services 8 (5) 275–285

49.

WhatGreenCar? Ratings Methodology". Whatgreencar.com. 2009-12-03. Retrieved from http://www.whatgreencar.com/emissionsanalysis.php.

50.

Welford R (1998). Corporate environmental management (2nd ed.),, Earthscan

Publications, London.

51.

World Energy Council (2007). "Transport Technologies and Policy Scenarios". World

Energy Council. Retrieved from http://www.worldenergy.org/publications/809.asp.

52.

Yan G, Paradi JC (1999). Success criteria for financial institutions in electronic commerce.

Proc. of the 32 nd

Hawaii International Conference on System Science.

53.

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer

Research, 12, 341–352.