Debt Burdens and a lack of Financial Literacy: Microfinance Crisis in

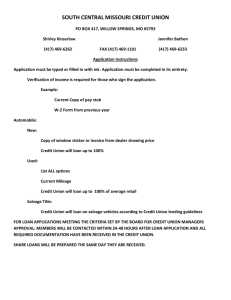

advertisement

Debt Burdens and a lack of Financial Literacy: Microfinance Crisis in the Indian State of Andhra Pradesh Venkataramana Gajjala, Ph.D. Associate Professor (Finance), School of Business, Tiffin University, 155 Miami Street, Tiffin, OH 44883 gajjalav@tiffin.edu Abstract In this paper, the author will examine how the rapid growth of Microfinance institutions (MFIs) during the last two decades – especially in the context of the more recent transition from nonprofits to for-profit nonbank finance companies (NBFCs) - has led to a significant increase in the delivery of financial services to the rural poor. In AP, the simultaneous existence of some of India’s most prominent and SHGs - with backing from the state and linkages to banks thus leading to relatively easy availability of funds - has led to a tremendous surge in the availability of credit across the state. However, this has caused a rivalry between the two competing models and has often resulted in borrowers drawing on multiple loans leading in some cases to over-indebtedness – media coverage in the second half of last year highlighted the suicides among the rural poor in AP. The bigger issue is therefore one of expanding the outreach of high-quality financial services while simultaneously avoiding customers’ overindebtedness. Keywords Microfinance, self-help groups, financial literacy, ultra poor, SKS, income generation, cash flow, budgeting, financial goal-setting, financial negotiation INTRODUCTION In recent years Microfinance has become globally prominent - this is witnessed by the proliferation of online microlending platforms such as Kiva.org and the increasing interest in Microfinance on the part of European and US based public and private organizations like, for instance, the US Agency for International Development. Also, advances in information and communication technologies (ICTs) have had economic and social impacts on MFIs around the world. These impacts can be viewed from the perspective of the end user and the MFI i.e. the impact on transaction costs, interest rates and the availability of credit (Gajjala, et al. 2011). Given that it has been thirty years since the inception of Microfinance, there is now an imperative need to examine whether MFIs have succeeded in their core objective i.e. making a serious impact on the alleviation of poverty. In cases where Microfinance has failed, possible causes have to be analyzed. For instance, the rapid growth of MFIs in India during the last two decades – especially in the context of the more recent transition from nonprofits to for-profit nonbank finance companies (NBFCs) - has led to a significant increase in the delivery of financial services to the rural poor (Akula, 2008). However, this has also led to many households availing of multiple loans thus significantly increasing their overall debt - and consequent problems with repayment - leading in some cases to tragic events. The intention here is to find ways for MFIs to deliver high-quality financial services while simultaneously protecting client interests. Further, the role of self-help groups (SHGs) in the Microfinance sector needs to be examined as well. Proponents of the SHG idea in India claim that despite sixty plus years of planned development, the rural poor still do not have access to credit. The reasons cited for this failure of the banking system - apart from the well-known failure of the state run rural development and poverty alleviation programs - are high transactional costs, inadequate banking infrastructure in rural areas and cumbersome documentation procedures. Several studies have been undertaken to assess why a majority of the poor were being bypassed by the formal banking system and whether the products and services offered by the system were appropriate for the requirements of the poor. These studies have confirmed that the poor continued to remain outside the fold of the formal banking sector’s policies, systems and procedures and further that the banking sector’s deposit and loan products were not suited to meet their most immediate needs. These studies have further revealed that from the demand perspective what the poor really needed was better access to these services and products rather than cheap and subsidized credit. This led to a search for alternative policies, systems and procedures, savings and loan products, other complementary services and new delivery mechanisms, which would fulfill the requirements of the poorest - especially women. The emphasis therefore was on improving the poor’s access to Microfinance rather than just microcredit. This led to the emergence of SHGs – a bank linkage model that could be used by the banks for increasing their outreach to the poorest of the poor, hitherto being bypassed by them. The model envisaged forming small, cohesive and participative groups of the poor, encouraging them to pool their savings regularly and using the pooled thrift for small interest-bearing loans to their members. This would enable the poor to learn the nuances of financial discipline in the process. MFIs IN ANDHRA PRADESH In the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh (AP), the mutual existence of the massive and well-funded SHG program (with backing from the state) and five of India’s biggest and fastest growing MFIs has led to an abundance of credit across the state. The SKS Microfinance IPOi last year underscored both the enormous potential that the MFI model has in scaling up and the vast prospects that it provides to advance financial inclusionii while simultaneously drawing attention to the similar potential that it has for making massive profits. This has fueled a rivalry between the two competing models often leading to borrowers availing of multiple loans thus causing over-indebtedness in some cases – a lack of financial literacy has exacerbated the problem. Media coverage (both electronic and print) in the second half of last year highlighted the tragic events among the rural poor who have been troubled with outstanding debt combining a wide range of consumption loans with production loans under the umbrella of “micro financing” – particularly in AP. The initial response of the government of the state of AP was to pass an ordinance - this has since been replaced by legislation - which seeks to cap interest rates and regulate the functioning of MFIs because of evidence of predatory lending, the interest rates charged and their “coercive” loan recovery methods that land the poor into a debt trap which eventually proves inescapable for some and consequently leads them to resort to suicides. Historically, interventions of this sort have the unintended consequences of reducing the availability of funds, as the risk to lenders is higher than the capped interest rate. The new law thus marks a paradigm shift - MFIs are no longer seen as benevolent and progressive institutions leading to equitable development. However, MFIs have defended the relatively high interest rates on the grounds of high transaction costs, the increased probability of default thus necessitating a significant risk premium - due to the unstable economic conditions of some of the borrowers and the expenditure incurred on more rigorous monitoring and efficient collection mechanisms (Akula, 2008). FINANCIAL LITERACY Financial literacyiii, which is the ownership of skills and knowledge that equip individuals to make prudent financial decisions, is a prerequisite for MFI borrowers given the lack of pricing transparency in microfinance and the fact that technology and innovation are making microfinance products increasingly complex. For example, mobile banking can be challenging for people with low levels of basic literacy skills. Further, financial literacy leads to better financial inclusion since prospective clients are more likely to use financial services once they are made aware of its potential benefits and obligations. As far as developing countries are concerned, comparatively limited research has been done on levels of financial literacy. However, development banks like the Asian Development Bank consider financial literacy education to be vital and private foundations like the Citi Foundation (funded by CitiGroup) have supported several programs to increase levels of financial literacy worldwide (Cole & Fernando, 2008). My objective in this paper is to analyze the programs being implemented by MFIs in AP to increase the level of financial literacy among the ultra poor - in the final analysis this will reduce loan defaults resulting from over-indebtedness and prevent tragic outcomes. I hypothesize that a) the level of financial literacy of the borrower, in general, is directly correlated to the likelihood that the loan(s) or outstanding loan(s) will be paid off on time and b) the deployment, quality, and delivery of information regarding the proposed loan provided by the MFI to the borrower regardless of the borrower’s financial literacy is directly correlated to the likelihood that a loan will be paid off on time. My investigation will consist of two steps: Step 1: I study the SKS Foundation’s Ultra Poor Program (UPP) first (in the section below) and why it was created - SKS is the parent organization of SKS Microfinance whose stated mission is to work alongside the ultra poor (it aims to be coterminous with SKS Microfinance which has outreach to 60,000 villages in 18 states in India with the ultimate objective of eliminating ultra poverty). SKS’ UPP was one of the pilot “global graduation program” - led by CGAP and the Ford Foundation - and was implemented in Medak district of Andhra Pradesh (Huda 2010). The UPP operated on the premise that the ultra poor needed an income generating activity to get out of poverty, but they were too helpless, too risk-averse and did not have the entrepreneurial abilities to benefit from microfinance. Over 400 women were carefully selected to participate in the UPP over an 18-month period from October 2007 to June 2009. Step 2: This will entail studying a sample of women who graduated from the UPP and have since become MFI borrowers. I will ascertain whether the level of financial literacy of the borrower, in general, is directly correlated to the likelihood that the loan(s) or outstanding loan(s) were paid off on time. I will also examine the level of loan knowledge among borrowers who have outstanding production loans and those with outstanding consumption loans. In addition, I will observe the training methods being adopted by the MFI loan officers at urban/suburban locations versus rural locations and larger versus smaller MFIs respectively and determine whether there is any difference in the deployment, quality, and delivery of information regarding the proposed loan in these two circumstances. The question that naturally arises and which I will try and answer is: assuming that these institutions are pursuing the same sic noble goals, why are very poor borrowers in AP experiencing high debt burdens leading in some cases to family tragedies that the media reports have highlighted and whether the lack of financial literacy is exacerbating the problem? My hypotheses include the following operational issues that are built into the methodology. Lending in the context of poor rural borrowers is operationally complex due to individual MFI loan officer performance targets and competitive pressures. Such practices include layering multiple loans on borrowers or paying off maturing loans with new loans at higher rates of interest and providing consumption loans to current borrowers (e.g. to finance a wedding in the family) who are already overleveraged simply to enable loan officers to meet their performance targets. This problem gets compounded as the MFIs are not regulated – hence the issue of regulation of MFIs or some sort of selfregulation needs to be looked into. POTENTIAL OUTCOMES I believe the benefits of improved financial literacy among rural poor borrowers, regardless of the loan intent (consumption versus production) should be: (1) lower rates of loan defaults, (2) followed by lower interest rates predicated on lower operating costs, and (3) more prudent borrowing decisions among the rural poor. The learning tools that can be developed include (some already exist and probably need to be refined): (1) borrower training materials for MFIs to provide as incentives to attract groups of potential borrowers, (2) the inception of rural loan counselors to mentor and support production loan borrowers and advise consumption loan borrowers in their decision-making, and (3) MFI loan officer training to balance their performance requirements with tempered lending policies. SKS’ ULTRA POOR PROGRAM SKS learned from experience that the poorest were excluded from the pilot “global graduation program” - led by CGAP and the Ford Foundation - which they had implemented in Medak district of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh (Huda 2010). SKS responded by creating the UPP - it operates on the premise that the ultra poor need an income generating activity to get out of poverty, but they are too helpless, too risk-averse and do not have the entrepreneurial abilities to benefit from microfinance. The UPP program encompassed 426 women over an 18-month period from October 2007 to June 2009. Extended income-generating assets, a cash allowance, a savings plan and health facilities for the duration of the program to a group of individuals who were meticulously selected based on certain criteria; Afforded a social safety net by building a community health fund and saving fund, which the ultra poor could access in times of need. Given SKS’s focus upon income generation and sustainability it firmly believes that financial literacy is a critical input in the process that enables the ultra poor to graduate out of poverty. Consequently, SKS incorporated a financial literacy component as part of its weekly training sessions, which emphasized income and expenditure tracking both for the household and the SKS supported enterprise, budgeting with a view to helping future financial goal-setting and saving. The curriculum for the financial module was developed after program administrators of the SKS UPP attended a workshop on ‘financial literacy for poor’ which was organized jointly by Freedom from Hunger and the Citigroup foundation - it was subsequently tweaked a little to suit local conditions (SKS NGO, 2011). Income and Expenditure (Cash flow) The purpose of this topic was to equip the ultra poor to handle income shocks due to uneven cash flows during the year by inculcating the saving habit – cutting down on wasteful expenditures is a prerequisite for this. The idea was to make them aware of their expenditure patterns, which would help them manage their money better - charts, fake money and a blank income and expenditure template were used as teaching aids. Field Assistants (FAs) conducted a survey of the Income and Expenditure pattern of each member separately and collected data on the sources and uses of income as shown in Figure 1 below which was then recorded in each member’s notebook. The data was then examined and the findings were shared with the members. Consolidated reports were then prepared on a monthly basis - for the entire duration of the module i.e. three months - and individually reviewed by the members. INCOME EXPENDITURE Cash in hand Expenditure on enterprise Members’ income from daily wages Food and consumption items Other family members’ income Health and medical expenditure Income from the enterprise Expenditure on other general items Income from SKS grant/allowance Credit/hand loan repayments Income from credit/hand loans Traveling cost Other income Misc. expenditure Total income Total expenditure Members’ weekly savings Balance cash in hand FIGURE 1: Source: Huda (2010) According to SKS, there were positive outcomes from this activity (sksngo.org). Members became sufficiently motivated to ascertain the price of the product(s) they were purchasing from the local merchants and some sought the assistance of their school going children to maintain a record of their daily income and expenditure. Further, after being counseled by FAs, some members even curtailed or eschewed their expenditure on alcohol and tobacco. Second, the data was also analyzed to ascertain the before and after income consequent upon the purchase of the asset – which was financed by SKS. SKS claimed that the average income gain across all members was INR 550 and that in most cases the gains were realized soon after the asset transfer mainly because of SKS’s choice of assets except where members opted for enterprises like the rearing of goats and pigs - the calves had to be raised for at least six months before they could be sold (SKS NGO, 2011). Concurrently expenditure wise, there was an increase in the expenditure on food and health care – the latter was in large part due to the FAs emphasizing the harmful effects of neglecting health issues. Repayment of credit and hand loans was an important expenditure item for most members and this typically improved after the asset transfer – during the lean season they were dependent on the local merchant for their daily needs like groceries, for instance, and invariably ended up paying more for credit purchases. Most of these loans were interest free but in case there was a delay, for example, in repaying cash borrowed from the local landlord or merchant the interest on the loan ended up being pretty huge. Budgeting The purpose of this topic was to teach the ultra poor the basics of budgeting over a period of three months -members were encouraged to review their scheduled expenditures and prepare for unforeseen expenditures. FAs reviewed expenses with two members at a time and carried out a budgetary exercise on a recommended format for the upcoming week. This was followed up with a meeting between the FAs and the members to examine if the budget has been adhered to and deviations (possibly due to health emergencies), if any, were discussed and ways to minimize cost overruns by relying on home made remedies were suggested. This budgetary exercise was subsequently extended to two other members of the group. Charts detailing income and expenditure items and fake money were used as teaching aids. Financial Goal-Setting The objective of this module was to make members go through a goal-setting exercise – it involved asking each member how they envisioned their enterprise to be in the future, the goal(s) they needed to set for themselves to translate that vision into and reality and, more importantly the sources of funds that they needed to achieve their goal(s). Taking a cue from the budgetary module, the member of that week was asked to demonstrate with rocks, the exact number of assets she possessed at that time, the number that she desired to have in the near future, and was asked to explain how she intended to achieve that goal (Huda, 2010). The member carried out a simulated exercise by using fake money to transact business with other members as her audience. The hope was that the group exercise would bring forth different ideas from which all members of the group could benefit. Financial Negotiations The purpose of this module was to teach members how to conduct financial negotiations in order to achieve the financial goals that they had set for themselves. Members were also told the difference between consumption loans and production loans – the former’s potential to land them into a debt trap and the importance of the latter in terms of generating income was emphasized. The game of snakes and ladders was used to demonstrate the potential drawbacks and advantages that are associated with the running of an enterprise and the importance of making the right choices was underscored. The members were introduced to the existence of different financial institutions in the village like the post office, SHG Bank linkages and MFIs – they were also informed about the procedural aspects relating to the utilization of the different financial products and services offered by each institution in order to enable them to make an educated choice based on their financial needs. As indicated earlier, training of MFI loan officers is absolutely critical in order to balance their performance requirements with tempered lending policies and this, in turn, is dependent on how welltrained they themselves are. Recognizing this need, SKS created a module to train the FAs and managers (trainers) who were responsible for training the potential beneficiaries of the UPP pilot. The trainers were put through a two-day orientation program – this included familiarization with the training materials and the conduct of mock training sessions designed to hone trainers’ skills in teaching basic household budgeting, cash flow analysis, income and expenditure forecasting and the creation of awareness among group members about the existence of various financial products and services (SKS NGO, 2011). The focus was on making the trainers realize the importance of participation by all the group members and the need to develop a methodical approach to achieve that objective. A white board, charts, flash cards, snake and ladder games, actual budgetary data pertaining to one or two trainees and fake currency were used in the training sessions, which were spread over two days. A detailed training report was required to be submitted at the end of the module. This was followed – after at least two months had passed - by a day’s refresher course where trainers’ reviewed their real time experience in the classroom. CONCLUSION As mentioned earlier, UPP brought together three modules: a) financial, b) social development and c) health. The objective of the UPP was to uplift ultra-poor women – who were too marginalized, too risk averse and lacked the necessary skills to successfully start and manage an enterprise – by providing them with productive assets, training in the running of a small enterprise and basic financial services like savings. In addition, they were also provided basic health services and consumption support. The idea was that once they had “graduated” out of extreme poverty they could generate income and diversify their asset base by making productive use of a MFI loan and ultimately break the vicious cycle of poverty. An evaluation of the SKS’ UPP indicated that the financial module had helped members to better organize their current expenditures and project their future expenditures (Huda, Lamhauge, & de Montesquiou, 2009). However, given that the ultra poor are forced to take on debt due to the financial shocks that they face (they cannot not rely solely on their assets or savings to deal with health emergencies, marriage expenses like dowry etc.) it is imperative that basic debt management training be incorporated in the module. This was the opinion that was voiced by members according to a study done to evaluate the SKS’ UPP (Huda, 2010). One line of action suggested by the trainers was to borrow from SHGs at concessional rates of interest if interest-free borrowing against group savings were insufficient – members were advised to avoid borrowing from moneylenders at exorbitant rates of interest. At a broader level, the question that arises is whether it is possible to scale-up the program to reach millions without losing the attention to detail that was a defining characteristic of SKS’ UPP - can there be a productive collaboration between the NGOs and the government and (Huda, 2010)? This is definitely a good topic for future research. Step 2 of the investigation (outlined above) is work in progress and I hope to get it done soon. REFERENCES Akula, V. (2008). Business Basics at the Base of the Pyramid. Harvard Business Review, 53-57. Retrieved May, 2011 from HBR.org. Cole, S., & Fernando, N. (2008). Assessing the Importance of Financial Literacy. ADB: Finance for the Poor, 9(3). Gajjala, V., Gajjala, R., Birzescu, A., and Anarbaeva, S. (Forthcoming August 2011). Microfinance in Online Space. Development in Practice, Huda, K. (2010). Overcoming Extreme Poverty in India: Lessons Learnt from SKS. IDS Bulletin, 41-4: (31-41). Huda, K., Lamhauge, N. & de Montesquiou, A. (2009). SKS Ultra Poor Pilot Mid-Term Evaluation: Summary Findings. Washington, D.C., CGAP. SKS NGO. (2010). Financial education to the ultra poor members. Retrieved, May 15, 2011 from http://sksngo.org/knowledgebank i SKS Microfinance – founded by Vikram Akula – is a for-profit NBFC that provides credit and insurance to the poor – especially women. ii Financial inclusion has been defined as the delivery of credit and other financial services at an affordable cost to the vast section of the disadvantaged and low income groups. Access to affordable financial services, especially credit and insurance, enlarges livelihood opportunities and empowers the poor to take charge of their life. iii A distinction could be made between financial literacy and financial awareness – the former refers to numeracy skills and the ability to understand complicated financial products while the latter refers to a basic knowledge of what financial products are available and the ability to make an informed choice about whether to use them. In this paper we will use financial literacy and assume that it includes financial awareness as well.