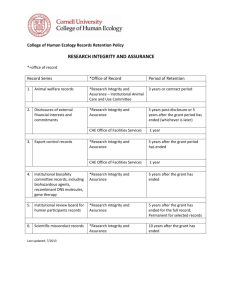

Evaluation

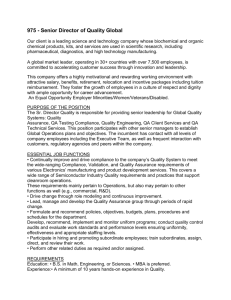

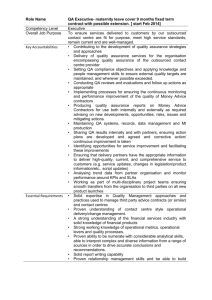

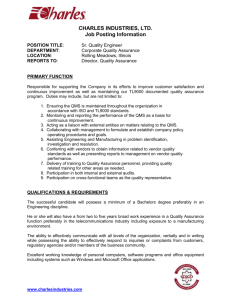

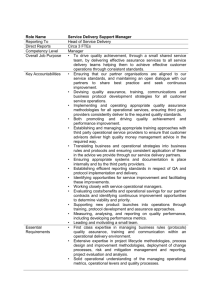

advertisement