Indian Journal of - Indian Gerontological Association

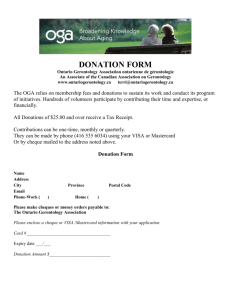

advertisement