Image and Sound

advertisement

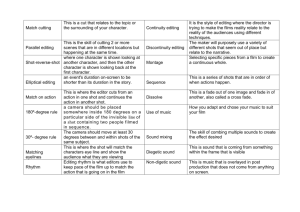

1 IMAGE AND SOUND Lecture 6 Editing: continuity and montage Key ideas The three main editing styles which filmmakers use for visual storytelling: Continuity The Long Take Montage [SLIDE 1 – Title] Today we are looking at editing This is something we have already been doing when looking at sequences shot by shot in tutorials. Editing controls what we see: the order in which we see it, and the timing and pace of the shots. Editing controls the pace at which the narrative unfolds. Editing can expand or condense time for dramatic effect. Editing also controls the order of the shots, what we see and don’t see and when we are allowed to see them. It controls the structure of the narrative as a whole and the subtle shifts in pacing of each scene. The process of editing involves selection and re-ordering of unedited raw footage – assembling often diverse fragments of moving images into an expressive, narrative structure. Editing also involves removing redundant footage and selecting only what is essential to advancing the story. I’m going to concentrate on three main editing styles which filmmakers use for visual storytelling: Continuity 2 The Long Take Montage These styles all developed in the first decades of film making, and form the basis of film language today. A filmmaker must be fully versed in these styles in order to know how to gather his or her raw footage in the appropriate way. In essence you are shooting simply so that you have something to edit. Continuity As you were shown in the last lecture, early filmmakers learned that instead of filming the action all in long shot they could break a scene down into a variety of different shot sizes and points of view to increase dramatic impact. They discovered ways of drawing the viewer into the film’s narrative space more effectively. The conventions of this style of shooting and editing came to be known as the Classical Hollywood Style which utilised the rules of what we call continuity editing. Continuity editing is a system of cutting that aims to maintain continuous and clear narrative action. It aims for smooth, seamless editing that links shots so that the cuts appear invisible to the viewer. Continuity editing relies upon visual elements matching from shot to shot. If screen direction, positioning of actors/elements, and temporal relations (creating a sense of the logical flow of time) are mismatched, then believability is jeopardised. A very humorous example of this is in the film the ‘King and I’ where his earring changes ear as the shots cut from one to another. Continuity editing draws our attention to the important parts of the action while disguising the cuts. Viewers become engaged in the story and don’t notice that the film is in fact made up of fragments cut together. The form and structure become invisible. Also the viewer’s gaze can be linked with the gaze of the characters. Sequence shot editing is where all the action is filmed in one static shot. 3 Lumiere Brothers clip: L' Arroseur arrosé, (1895) ... aka Tables Turned on the Gardener, aka The Sprinkler Sprinkled [SLIDE 2 – Lumiere] This was the first publicly screened narrative drama. Actors are aware of the film frame and ‘hitting their marks’. All is filmed in LS and shot in one take. It unfolds in ‘real time’ because they can’t compress time We saw last week how the introduction of the close up and a variety of shot sizes effectively drew the audience into the film’s narrative space. Today I’m going to examine more closely the ways in which this operates by looking at some of the rules of continuity editing and how they work within a sequence. In other words how does the continuity try to make itself as invisible as possible? Play Napoleon Dynamite clip (cafeteria scene where Napoleon’s friend gets a note from a girl) [SLIDE 4 – Cutting on action] Cutting on action This is a continuity cut which splices two different views of the same action together at the same moment in the movement, making it seem to continue interrupted [SLIDE 5 – 2 shot] Two shot – Shot-Reverse-shot cutting pattern This refers to a dialogue sequence which begins with a 2-Shot of the participants and then proceeds to cut from over-the-shoulder of one of the speakers to over-the-shoulder of the other. Occasionally a shot of one of the participants talking or listening will be cut into the pattern Eyeline matches Continuity editing dictates that if a character is looking in a certain direction in one shot, he / she should be looking in the same direction in the following shot. 4 This is crucial in the over-the-shoulder pattern, where characters must seem to be looking at one another (even if both actors are not physically present at the same time when the shots are made). Maintaining continuity of screen direction Continuity editing will attempt to keep screen direction consistent between shots. If a character or vehicle travels left-to-right across the frame in one shot, they must continue to observe the same screen direction movement in subsequent shots. Parallel cutting This is editing that alternates shots of two or more lines of action occurring in different places, usually simultaneously. [SLIDE 6 – Mastershot] Mastershot technique for shot coverage The master shot technique is used when shooting for continuity — an editing style that shows an action, preserving its logic and flow, but often with some compression of time. The main principle is that the action of the scene is shot a number of times, using different camera positions and angles each time. Of course, this means that the performers must repeat the action of the scene for each new camera set-up. Normally they start filming in long shot – a ‘master’ shot of the whole scene beginning to end. The master shot gets its name because it is wide enough to show all the action and all the characters in the scene. A master shot is often therefore a wide shot, but if the action takes place in a small area, it may be a medium shot or even tighter. Once the master shot has been recorded, the camera is moved and a series of tighter shots is recorded. These may be MCU or CU shots of each character, for example, and shots which emphasise important details in the scene. To get a smooth cut, the shot size and angle are changed for each new setup. 5 In each shot set-up, the entire action of the scene is recorded that is visible in that shot. This allows for maximum flexibility during editing, as the same actions can be seen in wide, medium and close-up shots. Because the action is repeated for each shot set-up, attention must be paid to continuity — in other words, the exact same actions must be performed, in the same order, for each shot set-up. Sometimes a sequence is filmed over a series of days but editing these shots together using rules of continuity makes them appear as if they were shot in the same time/place. Continuity cutting tries to preserve the flow of action so that it appears logical in terms of the representation of space and time. Napoleon Dynamite clip Two shot – Shot-Reverse-shot cutting pattern Cutting on action – throwing glance also Eyeline matches Mastershot technique Kill Bill clip - Mastershot Technique – play clip of Uma Thurman’s fight with Vivica A. Fox’s character [SLIDE 7 – Kill Bill] Screen direction Play clip of The Birds opening shot – Melanie Daniels walking into pet store and upstairs Screen direction maintained then into shot –reverse shot pattern [SLIDE 8 – Birds] Violations of continuity for dramatic effect: Play clip from The Birds: Lydia Brenner discovers Mr Fawcett dead with eyes pecked out Screen direction reversed / jump cuts 6 [SLIDE 9 – Birds] [SLIDE 10– Parallel] Parallel cutting Two actions or events portrayed as happening ‘simultaneously’ Editing that alternates shots of two or more lines of action occurring in different places, usually simultaneously A Girl and her Trust clip – play final sequence chase and rescue sequence up to last shot Continuity summation: Editing for dramatic intensity and emotional emphasis Use of parallel cutting, from one piece of action to another Selection of long, medium and close shots shifting the spectator’s point of view within a scene Positions the viewer inside the fictional space of the narrative Psychological identification with character and story (use of the closeup) Development of shooting and editing for continuity: temporal and spatial continuity – ‘invisible’ cuts (cutting on action etc.) Serves the requirements of seamless storytelling / clear linear narrative No jump cuts –jumps in real time that jar the sense of continuous flow No crossing the line –screen direction remains constant Matching reverse angles Long Take This is a shot that continues for an unusually lengthy time before the transition to the next shot. In an average film, shots last 3 – 9 seconds. A long take may last 60 seconds or more and contain complex camera movement. 7 Long takes might use crane or steadicam. They are highly choreographed (Russian Ark) Mise en scene is very important because of the changing compositional relationships between elements, how characters are arranged in relation to each other and to the setting. Play clip from Citizen Kane – clip of Kane as child playing in snow with sled– camera tracks back through window to interior scene with Kane’s mother signing papers with lawyer – play all of long until first cut. Montage Montage editing Intellectual montage Montage sequence Shots are juxtaposed to build dramatic tension; an approach to editing developed by the Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s.It emphasizes dynamic, often discontinuous, relationships between shots and the juxtaposition of images to create ideas not present in either shot by itself. The juxtaposition of a series of images to create an abstract idea not present in any one image. A segment of a film that summarizes a topic or compresses a passage of time into brief symbolic or typical images. Frequently dissolves, fades, superimpositions, and wipes are used to link the images in a montage sequence During the 1920s Montage was developed, and theorised, by a group of Soviet filmmakers including Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov and Lev Kuleshov The central aspect of Soviet Montage style was the area of editing. Cuts should stimulate the spectator. I n opposition to continuity editing, Montage cutting often used overlapping edits or repetition of shots which compressed or expanded time, or gave emphasis to certain actions. 8 Montage would also intercut and combine seemingly disparate shots to create new meanings, often making ideological points thus the idea of juxtaposition is central to montage. Through the juxtaposition of shots, new meanings can be created. e.g. Shot A and Shot B have distinct, individual meanings when considered separately. However the juxtaposition of A and B creates a third meaning as a result of their combination: A + B = C [SLIDE 11 – Kuleshov] In the Kuleshov experiment, he first filmed a Close Up shot of Ivan Mozhukin, a famous Russian actor with a neutral expression, and then separate shots of a bowl of soup, a young girl, and a child's coffin. He then cut the shot of the actor into the other shots; each time it was the same shot of the actor. Viewers felt that the shots of the actor conveyed different emotions suggested by the other stimulus, though each time it was in fact the same shot. The audience read into his blank expression hunger, paternal pride, and grief, respectively. The meanings then are in the juxtapositions, not in one shot alone. Meaning comes from the linking together of fragmentary details which might be totally unrelated in real life. Things to consider in Montage Exercise and Montage Assignment: 1. Montage sequences are built up from many separate shots. 2. Juxtapositions of shots can suggest emotional or psychological states, abstract ideas, moods, themes, or give added emphasis to a particular action 3. Long shots are rare. Montage often utilises close-ups – faces, objects, details – so it’s important to get in close enough to the subject of your shot. Close-ups are also more effective in montage as audience often has a very short time to register the content of a shot. Purpose of film editing: ‘Cuts should stimulate the spectator’ Intensify action 9 Compress or expand time with overlapping edits or repetition of shots Can be used to create an impressionistic effect or establish a particular mood To create the sense of a particular location or environment To express a particular theme, idea or ideology [SLIDE 12&13 – Montage examples] Russian Theorists Leo Kuleshov- experimented by cutting up existing films and re-assembling them V.I. Pudovkin- juxtaposition of images more important than the performance of the actor Sergei Eisenstein- collision theory The conflict of two shots produces a whole new idea. This way of editing became known as thematic montage Battleship Potemkin directed by Sergei Eisenstein (1925) - the collision of shots in the famous ‘Odessa Steps’ sequence produces an intense depiction of violence – note how last shots of appear to show a Cossack attacking a woman with his sword but we don’t actually see the sword make contact with the body of the victim – the impression of the attack is created purely through the technique of montage editing – the juxtaposition of the separate shots. Play Battleship Potemkin clip – play about a minute extract from the end of the ‘Odessa Steps’ sequence – ends on Cossack attacking woman with glasses [SLIDE 14 – Continuum] Realism – Continuity – Classical – Thematic montage - Abstract Conventions of classical cutting Matching action Classical editing tries to achieve: 10 o No jump cuts –jumps in real time that jar the sense of continuous flow o No crossing the line –screen direction remains constant Matching reverse angles Dream / fantasy / flashback sequences disrupt the normal flow of time – usually signalled by dissolve, black and white, music crescendo Parallel cutting – two actions portrayed as happening ‘simultaneously’ [SLIDE 15 – Reading for tutorial] Reading: Read the glossary of Editing terms pdf Summary Editing controls what we see: the order in which we see it, and the timing and pace of the shots. Editing controls the pace at which the narrative unfolds. Editing can expand or condense time for dramatic effect. Editing also controls the order of the shots, what we see and don’t see and when we are allowed to see them. Continuity Cutting on action Two shot – Shot-Reverse-shot cutting pattern Eyeline matches Maintaining continuity of screen direction Parallel cutting Mastershot technique for shot coverage Continuity summation: Editing for dramatic intensity and emotional emphasis Long Take 11 Montage Purpose of film editing: o ‘Cuts should stimulate the spectator’ o Intensify action o Compress or expand time with overlapping edits or repetition of shots o Can be used to create an impressionistic effect or establish a particular mood o To create the sense of a particular location or environment o To express a particular theme, idea or ideology Realism – Continuity – Classical – Thematic montage - Abstract Conclusion It is important for you to be able to recognise the three main types of editing i.e. Continuity The Long Take Montage so that you are familiar with the director’s intent and priorities and can identify the conventions of each style. In this way, you will be better able to read visual texts at a higher and more complex level.