Document

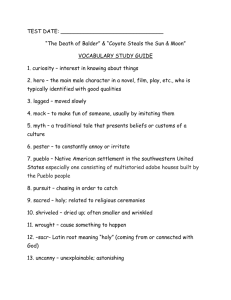

advertisement

1. Could one say Ceremony is a reinterpretation of the old legends? Well, no, it’s not a reinterpretation. I think their spirit is unbroken because of the oral tradition. If you think, 500 years, that is how long Europeans are in the Americas, is not a very long time. Because for 18,000 years there is eveidence, and perhaps longer, of the Pueblo people being in that land. . . The interpretation of the old stories remains the same because of the oral tradition. It goes backthrough time so that the immediacy is now. It is very important how time is seen. The Pueblo people and the indigenous people of the Americas see time as round, not as a long linear string. If time is round, if time is an ociean, then something that happened 500 years ago may be quite immediate and real, where as something inconsequential that happened an hour ago could be far away. Think of time as an ocean always moving. . . . the passage of [500 years] . . . does not mean the same thing to us as it might mean in a culture where the people stretch the string out and say Oh! This was a long time ago. That is not the way my people experience time. (Leslie Marmon Silko, interview) 2. We are the land, and the land is mother to us all. There is not a symbol in [Ceremony] that is not in some way connected with womanness, that does not in some way relate back to T’she and through her to the universal feminine principle of creation: Ts’its’tsi’nako, Thought Woman, Grandmother Spider, Old Spider Woman. All tales are born in the mind of Spider Woman, and all creation exists as a result of her naming. We are the land. To the best of my understanding, that is the fundamental idea that permeates American Indian life; the land (Mother) and the people (mothers) are the same. As Luther Standing Bear has said of the Lakota people, “we are of the soil and the soil is of us.” The earth is the source and the being of the people, and we are equally the being of the earth. The land is not really a place, separate from ourselves, where we act out the drama of our isolate destinies; the witchery makes us believe that false idea. (Paula Gunn Allen, “The Feminine Landscape of Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony”) 3. Tayo is a hero, like the legendary Sun Man who, with Spider Woman’s help, retrieved the storm clouds from the Gambler. He has succeeded, with T’seh’s help, in retrieving the mixed-breed cattle annd once again brought life-restoring moisture to his homeland. But Tayo becomes a hero in yet another sense not readily apparent from the novel alone. This sense of heroism is implicit in the book, though, and comes to the surface once one knows about the importance Puebolo cultures place on androgyny. Pueblo village chiefs, nearly always men, are sometimes addressed as “Our Father and Our Mother.” This form of address expresses respect for their presumed wisdom, a kind of wisdom that must come from an integration of opposites, which is not possible if one is only male or only female. The chief must be able to perform male-associated tasks such as discerning when to fight or go to war; but the chief is expected to embody values that are traditionally considered female as well: he must protect and look after the village people as a nurturer as well as a warrior. (Jude Todd, “Knotted Bellies and Fragile Webs”) 4. All summer the people watch the west horizon, scanning the sky from south to north for rain clouds. Corn must have moisture at the time the tassels form. Otherwise, pollination will be incomplete, and the ears will be stunted and shriveled. An inadequate harvest may bring some disaster. Stories told at Hopi, Zuni and at Acoma and Laguna describe drought and starvation as recently as 1900. . . [Yet] the ancient Pueblo people not only survived in this environment, but in many years they thrived. In A.D. 1100 the people at Chaco Canyon had built cities with apartment buildings of stone five stories high. Their sophistication as sky-watchers was surpassed only by Mayan and Inca astronomers. Yet this vast complex of knowledge and belief, amassed for thousands of years, was never recorded in writing. Instead, the ancient Pueblo people depended upon collective memory through successive generations to maintain and transmit an entire culture, a world view complete with proven strategies for survival. The oral narrative, or “story,” became the medium in which the complex of Pueblo knowledge and belief was maintained. Whatevedr the event or the subject, the ancient people perceived the world and themselves within that world as part of an ancient and continuous story composed of innumerable bundles of other stories. The ancient Pueblo vision of the world was inclusive. The impulse was to leave nothing out. Pueblo oral tradition necessarily embraced all levels of human experience. Otherwise, the collective knowledge and beliefs comprising ancient Pueblo culture would have been incomplete. Thus stories about the Creation and Emergence of human beings and animals into this World continue to be told each year for four days and four nights during the winter solstice. The “humma-hah” stories related events from the time long ago when human beings were still able to communicate with animals and other living things. But beyond these two preceding categories, the Pueblo oral tradition knew no boundaries. Accounts of the appearance of the first Europeans in Pueblo country or of the treagic encounters between Pueblo people and Apache raiders were no more and no less important than stories about the biggest mule deer ever taken or adulterous couples surprised in cornfields and chicken coops. Whatever happened, the ancient people instinctively sorted events and details into a loose narrative structure. Everything became a story. (Silko, “Landscape, History and the Pueblo Imagination”) 5. Pueblo potters, the creators of the petroglyphs and oral narratives, never conceived of removing themselves from the earth (Corn Mother) and sky (Sun Father or Sun Sister). So long as the human consciousness remains within the hills, canyons, cliffs and the plants, clouds and sky, the term landscape, as it has entered the English language, is misleading. “A portion of territory the eye can comprehend in a single view” does not correctly describe the relationship between the human being and his or her surroundings. This assumes the viewer is somehow outside or separate from the territory he or she surveys. Viewers are as much a part of the landscape as the boulders they stand on. jThere is no high mesa edge or mountain peak where one can stand and not immediately be part of all that surrounds. Human identity is linked with all the elements of Creation through the clan: you might belong to the Sun Clan or the Lizard Clan or the Corn Clan or the Clay Clan. Standing deep within the natural world, the ancient Pueblo understood the thing as it was – the squash blossom, grasshopper or rabbit itself could never be created by the human hand. Ancient Pueblos took the modest view that the thing itself (the landscape) could not be improved upon. The ancients did not presume to tamper with what had already been created. Thus realism, as we now recognize it in painting and sculpture, did not catch the imaginations of Pueblo people until recently. The squash blossom is one thing: itself. So the ancient Pueblo potter abstracted what she saw to the be the key elements of the squash blossom – the four symmetrical petals, with four symmetrical stamens in the center. These key elements, while suggesting the squash flower, also link it with the four cardinal directions. By representing only its intrinsic form, the squash flower is released from a limited meaning or restricted identity. Even in the most sophisticated abstract form, a squash flower or a could or a lightning bolt became intricately connected with a complex system of relationships the Pueblo people maintained with each other, and with the populous natural world they lived within. . . . Pictographs and petrogylphs of constellations or elk or antelope draw their magic in part from the process wherein the focus of all prayer and concentration is upon the thing itself, which, in its turn, guides the hunter’s hand. Connection with the spirit dimensions requires a figure or form which is all-inclusive. A “lifelike” rendering of an elk is too restrictive. Only the elk is itself. A realistic rendering of ann elk would be only one particular elk anyway. The purpose of the hunt rituals and magic is to make contact with all the spirits of the elk. (Silko, “Landscape, History and the Pueblo Imagination”)