2.3. Main challenges and risks to e-Government

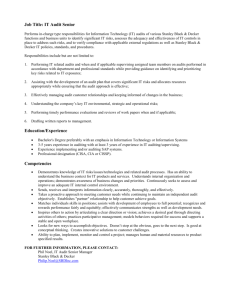

advertisement