AG Speech – “Historical Developments in Evaluation and Auditing

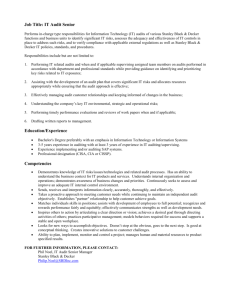

advertisement