Money and Banking

advertisement

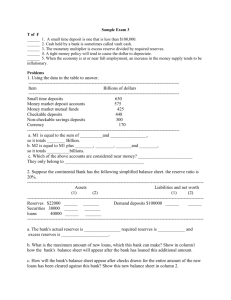

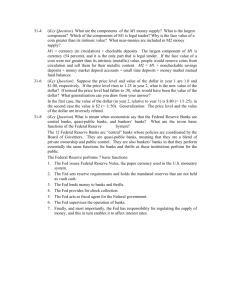

Money and Banking What is money? Where does it come from? What purposes does it serve? To what extent can we control the amount and disposition of money? The answers to these questions are a very significant part of the foundation of the macroeconomy. Money is essential in promoting the level of exchange and savings/investment essential to maintaining and expanding a nearly $10 trillion economy. This chapter takes up the questions of what money is and is not, where it comes from, what gives money its value, and how banks and the banking system can influence and control the supply and disposition of money. Chapter 13 will continue this discussion, turning to the institution that oversees the U.S. banking system and the supply of money in the U.S. economy: the Federal Reserve System (the Fed). CHAPTER OBJECTIVES Upon completing this chapter, your students should be able to: 1. Discuss how money evolved out of a barter economy. 2. List and explain the functions of money. 3. Explain what gives money its value. 4. Define the money supply. 5. Explain why credit cards are not money. 6. Explain how banking developed. 7. Explain the role banks play in the money creation process. KEY TERMS • • • • • • • • • • • • • money barter medium of exchange unit of account store of value double coincidence of wants Gresham’s Law M1 Currency Federal Reserve Notes checkable deposits M2 time deposits • • • • • • • • • • • • savings deposits money market deposit account money market mutual fund fractional reserve banking Federal Reserve System (the Fed) reserves required-reserve ratio (r) required reserves excess reserves T-account simple deposit multiplier cash leakage CHAPTER OUTLINE I. MONEY: WHAT IS IT, AND HOW DID IT COME TO BE? A. Money: A Definition—Though often confused with other things, such as income, wealth, and credit, money is any good that is widely accepted in exchange of goods and services, as well as the payment of debts. B. Three Functions of Money—Perhaps the best way to define money is to look at the functions it serves. 1. Money as a Medium of Exchange—If there were no money, goods would have to be exchanged through the process of barter; that is, goods would be traded for other goods in transactions arranged on the basis of mutual need. For example, if I make shoes and want to “purchase” some bread, I would have to find a baker who needs shoes and then arrange to trade him shoes for bread—that is, there must be a double coincidence of wants. Money eliminates the need for such arrangements and the (often prohibitive) transaction costs that accompany arranging such trades. In a money economy, money, rather than goods, is the medium of exchange via which transactions are made. 2. Money as a Unit of Account—In a money economy, all goods, services, and debts are valued in terms of money. As such, money is the unit of account—the common standard by which value is determined. 3. Money as a Store of Value—The store of value function refers to money’s ability to retain its value over time. Since all transactions are made in money, and all values are based on money, money should also retain its value. C. From a Barter to a Money Economy: The Origins of Money—Money was not “invented” by some clever government clerk or “ordained” by a ruler. The first forms of money simply developed out of the barter process. Even though barter involved trading goods for goods, some goods—those that were commonly needed—were more readily accepted than others. Over time, as people began more and more to accept one or more particular item(s) in trade—even when they had no particular use for them, but felt they could always trade these goods for what they did need—widely accepted media of exchange sprang up. Soon after, people began to fix values of their wares in terms of this (these) particular item(s), thereby establishing a reliable unit of account. Then it was only a matter of time until economies moved to goods like gold and silver, which did not perish and would retain their value over time. D. Money, Leisure, and Output—Money makes it easier to conduct transactions, therefore, money economies should have more leisure time for their citizens than barter economies. The double coincidence of wants is a time-consuming process! E. What Gives Money Its Value?—Under a system in which money was “backed” by gold and/or silver, the value of money was determined by the value of its commodity base. In today’s world no gold backs the U.S. dollar. Instead, the dollar’s value is established by its general acceptability in exchange for goods and services. F. Gresham’s Law: Good Money, Bad Money—Sir Thomas Gresham was the finance minister for Queen Elizabeth I of England. Gresham’s Law states that bad money drives good money out of circulation. That is, if there are two types of coins in circulation and one is perceived as less valuable, the good or more valuable money will be hoarded and people will only exchange the less valuable coins. II. DEFINING THE MONEY SUPPLY—Just because we (may or may not) know what money is, that does not mean that we know exactly how the theory translates into the “real world.” Here we discuss the two most frequently used empirical definitions of money: M1 and M2. A. M1—M1 consists of currency outside banks plus checkable deposits plus traveler’s checks. (See Exhibit 1.) 1. Currency Held Outside Banks—This includes coins minted by the U.S. Treasury and paper money, which is the legal tender of the U.S. government; about 99 percent consists of Federal Reserve Notes issued by the Federal Reserve district banks. 2. Checkable Deposits—These are funds on which checks can be written. 3. Traveler’s Checks—Issued in specific denominations, these are treated as cash. So, M1 = Currency held outside banks + Checkable deposits + Traveler’s checks B. M2—A broader definition of the money supply, it includes all of the components of M1 plus small-denomination time deposits plus savings deposits plus money market deposit accounts plus noninstitutional money market mutual fund accounts 1. Small-denomination Time Deposits—interest-earning deposits with a specified maturity, which are subject to penalty for early withdrawal. Small-denomination time deposits have a value of less than $100,000. 2. Savings Deposits—interest-earning deposits with no specific maturity or maximum value, but which may require advanced written notice of withdrawal. Money Market Deposit Accounts (accounts that take savings and invest them in short-term financial instruments, pay higher-thansavings-account interest, and offer limited check-writing privileges) are also included in this category. 3. Money Market Mutual Funds (noninstitutional)—interest-earning accounts at a mutual fund company. MMMF accounts held by institutions are not counted in M2 C. Where Do Credit Cards Fit In?—Credit cards are commonly referred to as “plastic money.” In fact, credit cards are not money, but rather devices by which money is lent—money that must be paid back. Thus, if we counted the value of credit card balances, as well as the value of the money that must be used to pay those balances off, we would be guilty of double counting. III. HOW BANKING DEVELOPED A. The Early Bankers—In days of yore, most money was in the form of gold coins, which were heavy and difficult to transport. Seeing an entrepreneurial opportunity, goldsmiths began to offer gold storage services in addition to their coining and melting services. In return for a customer’s gold, the smith would issue a warehouse receipt, which became a form of money accepted in lieu of the gold itself. The growing acceptance of receipts and the infrequency with which they were ever actually “cashed in” for the gold they represented led smiths to believe that they could begin lending out part of their customers’ gold and/or printing receipts in excess of actual gold holdings. In so doing, the system of fractional reserve banking, whereby banks create money by holding only a portion of their deposits on reserve, was born. B. The Federal Reserve System—The Federal Reserve System is the central bank for the United States. Its chief function is to control the nation’s money supply. IV. THE MONEY CREATION PROCESS A. The Bank’s Reserves and More—Just as individuals have deposits at banks, banks have deposits at the Fed. 1. Reserves—Total reserves equal the amount of cash in the bank’s vault plus the value of funds held on account at the Federal Reserve. Neither vault cash nor money held on account at the Fed earns interest. 2. Required Reserves and Excess Reserves—Bank reserves may be separated into two categories: required reserves and excess reserves. Required reserves are the amount of reserves a bank must hold against deposits, as mandated by the Fed’s required-reserve ratio. Excess reserves are any reserves held above and beyond the required amount. 3. Lending Excess Reserves—Banks may lend their excess reserves either to their customers or to other banks in order to earn interest on the loan. B. The Banking System and the Money Expansion Process—Individual banks are prohibited from printing their own money. Nevertheless, banks may create money by creating checkable deposits, which are a part of the money supply. In order to see this, let’s work through the process step-by-step. Step One: Suppose the Fed prints $1,000 and decides to deposit it in Bank A. Step Two: Bank A sets aside the portion of that $1,000 that is required reserves. For this example, assume that the required reserve ratio is 10 percent. So, $100 is set aside, and the remaining $900 becomes excess reserves. Step Three: Bank A decides to lend that $900 to Jenny, who then deposits that $900 in her account. At this point, the money supply has increased. The $1,000 the Fed printed remains in the system, and we can now add Jenny’s $900 to this. Step Four: Jenny’s Bank B sets aside 10 percent of her $900—that is, $90— as required reserves. The remaining $810 becomes excess reserves. Step Five: Jenny’s Bank B now has $810 that may be lent—an action that will increase the money supply again. 1. How Far Does it Go?—The process continues until no new excess reserves can be created. The maximum amount of new money that may be created from any new money can be derived using the formula: Maximum change in checkable deposits = 1/r R where r = the required-reserve ratio and R = the change in total reserves resulting from the initial injection of funds. 2. The Simple Deposit Multiplier—The expression (1/r) in the formula above is known as the simple deposit multiplier. C. Why Maximum? Answer: No Cash Leakages and Zero Excess Reserves—The deposit multiplier formula above can only tell us the change in money supply if we accept a couple of underlying assumptions: first, all funds are deposited into bank checking accounts—that is, there is no cash leakage (no cash held out before depositing) and there are no noncheckable deposits—and second, banks do not voluntarily hold excess reserves. D. Who Created What?—To summarize the money expansion process, there were two major players: the Fed and the banking system. The Fed directly created $1,000, which made it possible for banks to create $9,000 in checkable deposits. The formula for finding out how much money the banking system can create out of any given amount of funds is: Maximum change in checkable deposits (brought about by the banking system) = 1/r × ER where r = the required-reserve ratio and ER = the change in excess reserves of the first bank to receive the initial injection of funds. E. It Works in Reverse: The “Money Destruction” Process—The process described above works equally well in reverse. In this case, the Fed removes $1,000 from the banking system, creating a shortage of reserves. To remedy that shortage, banks reduce lending and/or sell assets (e.g., government securities), thereby reducing the money supply. F. We Change Our Example—The Fed isn’t the only actor in the economy who can get the money expansion ball rolling. If Jack had been hiding $1,000 in a shoebox and decided to take the money out and deposit it in the bank, he would add money to the banking system that could be lent out to other depositors. The money expansion process would now evolve in the same process as when the Fed printed $1,000. The Federal Reserve System Chapter 12 introduced us to money, its role in the economy, and the degree to which the banking system can “create” money and control the supply of money. Most of the responsibility for creating and controlling money rests upon the broad shoulders of the Federal Reserve System, or “The Fed” for short, the central bank of the United States. Chapter 13 examines the structure and purpose of the Fed and then turns to a detailed study of the tools with which the Fed controls the supply of money: open market operations, the required reserve ratio, and the discount rate. CHAPTER OBJECTIVES Upon completing this chapter, your students should be able to: 1. Identify and discuss the functions of the Federal Reserve System. 2. Outline the structure of the Fed. 3. Explain how checks clear. 4. Identify and discuss the tools the Fed can use to change the money supply. 5. Explain the difference between the federal funds rate and the discount rate. KEY TERMS • Board of Governors • open market sale • Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) • reserve requirement • open market operations • federal funds market • U.S Treasury securities • federal funds rate • open market purchase • discount rate CHAPTER OUTLINE I. THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM A. The Structure of the Fed—The Federal Reserve System was created by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Its principal components are the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee and the 12 Federal Reserve District Banks. The boundaries of the twelve Federal Reserve Districts are shown in Exhibit 1. 1. Board of Governors—The Board of Governors controls and coordinates the activities of the Federal Reserve System. The seven governors are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate to staggered 14-year (non-renewable) terms. The president designates one member of the board as the chair for a four-year, renewable term. 2. Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)—The major policy-making group within the Fed, the FOMC is made up of the seven governors plus five presidents of Federal Reserve District Banks (the president of the New York Fed has a permanent seat; the other four places rotate among the remaining 11 Federal Reserve District Bank presidents). The authority to conduct open market operations—the buying and selling of government securities for purposes of manipulating the money supply— rests with the FOMC, and it is the responsibility of the New York Fed to carry out FOMC orders. 3. Federal Reserve District Banks—To assist the Board of Governors in overseeing the banking system and controlling the money supply, the system is divided into 12 geographic districts, and a Federal Reserve District Bank president oversees each Federal Reserve District Bank. B. Functions of the Federal Reserve System—The Fed has eight major functions: 1. Control the Money Supply—This will be explained in detail later in the chapter. 2. Supply the Economy with Paper Money (Federal Reserve Notes)— The Federal Reserve banks have Federal Reserve Notes on hand to meet the needs of banks and the public. 3. Provide Check-Clearing Services—When someone writes a check that is deposited in some bank other than the one it was written on, some arrangement must be made to transfer funds between the two banks. Rather than handle each transaction separately, most banks use a clearinghouse operation, which keeps track of each bank’s claims against each other bank, determines who owes who what at the end of the day, and makes the necessary transfers. The Fed provides such services. This process is summarized in Exhibit 2. 4. Hold Depository Institutions’ Reserves—All depository institutions must keep a certain portion of their funds “on reserve,” either as vault cash or on account at the Fed. These accounts are maintained by the Federal Reserve banks for member banks in their respective districts. 5. Supervise Member Banks—The Fed conducts periodic examinations and audits of member banks. 6. Serve as the Government’s Banker—The federal government collects and spends hundreds of billions of dollars annually in the form of taxes, transfers, purchases of goods and services, payroll, and interest and principal payments on debt. The Fed is the primary holder of U.S. government deposit accounts. 7. Serve as a Lender of Last Resort—When individuals need a loan, they go to their local bank. But where does their local bank go when it needs a loan?—To the Fed, of course. The Fed acts as a “lender of last resort,” providing funds to banks suffering liquidity problems. 8. Serve as a Fiscal Agent for the Treasury—The U.S. Treasury often auctions Treasury securities to help pay the cost of running the government and all of its policies. The Fed aids the Treasury in conducting the weekly auctions. Remember, the U.S. Treasury manages the financial affairs of the government, collecting taxes, and making payments; the Fed’s job is to oversee the monetary system for the country as a whole. II. FED TOOLS FOR CONTROLLING THE MONEY SUPPLY A. Open Market Operations—Anytime the Fed buys or sells anything, it affects the money supply. The main “thing” the Fed buys and sells is U.S. government securities, using open market operations. 1. Open Market Purchases—When the Fed purchases government securities from the nonbank public or from a bank, it does so with money that did not “exist” prior to the transaction. Thus, when the Fed makes the purchase, bank reserves will rise—either directly, in the case of the Fed purchasing from a bank, or indirectly, when the individual seller deposits his Fed check in his bank account and the money supply will increase. 2. Open Market Sales—When the Fed sells government securities to banks and others, bank reserves will decrease and the money supply will decrease. B. The Required Reserve Ratio—The Fed can also influence the money supply by changing the required reserve ratio. Recall that banks must hold a specified percentage of all deposits on reserve; this requirement limits the amount by which banks may expand the money supply. If the Fed increases the reserve ratio, the simple deposit multiplier will be smaller, thereby further limiting the amount by which banks may expand the money supply. If the Fed decreases the reserve ratio, the simple deposit multiplier will be larger, thereby enabling banks to expand the money supply by a greater amount. C. The Discount Rate—Banks not only provide loans to their customers, they also borrow funds when needed. Why might a bank need to borrow funds? Perhaps the bank has a good loan candidate, but lacks the funds to make the loan. Or the bank may be experiencing a reserve deficiency. In either case, the bank has a choice to make: 1. Borrowing in the Federal Funds Market—One of the two places where the bank could turn is the federal funds market, where it borrows excess reserves from another bank. The rate of interest it pays on such a loan is called the federal funds rate. 3. Borrowing from the Fed—The other choice is to borrow from the Fed, using the discount window. The rate of interest paid for bank loans from the Fed is called the discount rate. D. The Spread between the Discount Rate and the Federal Funds Rate—The decision on where to borrow depends upon a number of factors, the most important of which is the lower interest rate. However, even if the discount rate is lower, the bank may still choose to borrow in the federal funds market. Why? First, the Fed may restrict the amount of funds available. Second, the bank may not feel the Fed will “approve” of its reasons for borrowing and knows that it will face significant bureaucratic problems. As a result, the bank may make its decision based upon the “spread” between the rates. If the discount rate is only slightly lower than the federal funds rate, the bank will likely choose federal funds. However, if the spread is significant, the bank may decide the interest saved is worth the administrative hassles associated with borrowing from the Fed. E. Which Tool Does the Fed Prefer to Use?—The Fed may wish to control the money supply through the discount rate, open market operations, or the required reserve ratio. Why does it prefer one over the others? Exhibit 4 summarizes the tools. 1. Open Market Operations—The Fed uses open market operations more than the others. The reasons are that (1) open market operations are flexible in the size of the transactions; (2) they can be easily reversed if need be; and (3) they can be implemented quickly.