IKEACase

advertisement

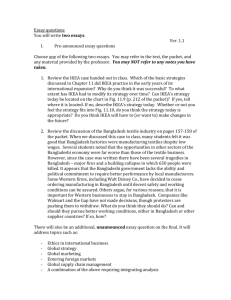

Case Study – IKEA Trading Area Poland Introduction Go into an IKEA store and you will notice that it is essentially self-service and, once you get your purchase home, self-assemble. Most business commentators have held this up as an example of a clever retailing operation – many of the usual costs have been passed to the customer, such as finding the item in the warehouse. However, a close look at the whole IKEA operation reveals that the layout and service in their stores is just the outward, customer-facing evidence of a highly efficient supply chain that goes right back to the raw material in the forest. What is striking about IKEA’s business model is the analysis in minute detail of all costs in the value chain from the tree ‘on the root’ through sawmilling, plank or chipboard production, component manufacture, packing, storage and transport at every stage in the chain through to the customer’s trolley. It is seen as irrelevant whether the materials are in IKEA’s ownership or in the hands of their suppliers and sub-suppliers at any particular stage. The supply chain is the entity and all the legal trading entities that participate in the delivery of any particular product do so in a boundary-less way. For example, accompanying an IKEA team around one of their suppliers’ factories one is struck by the familiarity the team members have with the layout and processes on the shop floor, the stocks of raw material and where they come from, the outbound logistics down to the way that the lorries are packed. They greet their opposite numbers as if they are colleagues in the same firm and there is no trace of wariness or the traditional adversarial customer-supplier relationship. The IKEA Structure IKEA’s structure is designed to optimise the efficacy of the design and supply processes. It is split into 4 distinct parts that operate as a type of internal market. IKEA of Sweden (IOS) has the headquarters function. It is split into 12 Business Areas aligned to products (e.g. sofas, dining furniture, beds etc.). Under IOS the Retail Division controls all the stores, the Distribution Centres are likewise grouped under distribution and the Trading Areas deliver the purchasing and supplier support functions. IKEA of Sweden ( IOS) Headquarters, design and marketing functions Retail Distribution Trading Areas (Purchasing, logistics & supplier support The way that the internal market works is that the Business Area Manager commissions a product using an integrated project team that includes a designer (either freelance or from one of IKEA’s 2 design schools in Sweden), a technician and a product developer. The ‘Istra’ (the marketing decision maker in the Business Area) will then set up a competitive tender to decide the country of production. The trading areas compete to win the contract to supply that product or product range, either globally or regionally, in a tender process. Thus Trading Area Poland will cooperate with manufacturers in Poland to supply it at the best possible price, the criteria being the ‘landed price’ at IKEA stores taking into account all materials, processing and logistics costs along the way. This sourcing system manages to be highly competitive and un-adversarial at the same time. The TA Poland team are in effect ‘on the same side’ as the suppliers in the Central European region: they are helping them to put the tender together to win the competition against manufacturers in the Far East or elsewhere. This will involve looking not just at price but searching for production capacity and economies in raw material supply and efficient logistics. Case Study: The Alve Office Furniture Range TA Poland and pine furniture manufacturer Formaplan have worked together to win the business of supplying a new range of office furniture globally. The project has involved developing new staining and lacquering skills to win the confidence of IOS that they can produce the brown pine furniture to a high standard. They had to submit prototypes for Istra approval. They have had to concentrate production on a short supply chain in a pine forest area south of Warsaw to be able to deliver a landed price anywhere in the world that competes favorably with suppliers in other regions. The whole chain is as short as 30-60km, depending on where the timber is sourced, from the forest to the dispatch of finished goods to the distribution centers. IKEA is assisting Formaplan to build a railhead at their finishing plant to ensure that onward distribution costs as little as possible. IKEA logistics Experts have also assisted with advice on the packaging and the packing of items in the containers, focusing on a 60% filling rate. Formaplan will start to supply the furniture on an OPDC basis (Order Point Distribution Centre) basis with a 20 working days lead time initially. Once the test run on the product has happened and sales of the product settle down to a more predictable rate the intention is for Formaplan to ‘climb the supplier ladder’ to shorter delivery times, initially to 15 working days. IKEA will determine the service level for the Alve range that equates to the required availability of the product in the retail stores, usually 90-99%. This will in turn dictate the quantity of buffer stocks that Formaplan have to hold. The expectation is that as the accuracy of forecasting improves the requirement to hold stock will go down. Formaplan will have complete transparency of all IKEA’s stockholding of the product at warehouses and stores to assist them. This is a big step for Formaplan. IKEA accounts for 40% of their business. They do not stand to make huge margins from Alve but the volumes that IKEA guarantee will help them to expand and they know that all being well it will be a lasting relationship. Case Study – CIMIR sofa manufacturer CIMIR in Brodnica, 2 hours north of Warsaw, is an IKEA supplier on the inside track. The company’s founder was an IKEA manager in Sweden who then left to set up a manufacturing company in Poland, serving the European market, and Mexico, serving the North American market. In 10 years the company’s turnover in Brodnica has grown to €20m on 16000 m2 of factory floor with a headcount of 400. The capacity is 500 sofas today with a surge capability of 600. They have just changed their supply contract with IKEA. Previously they were manufacturing on a JIT basis and delivering direct to stores on a 2 week lead time. They are now working on an OPDC basis with a 5 day lead time, this necessitates holding limited stock; no more than one week’s worth depending on the season and the proximity to a catalogue launch. The next step is to move to a 3 day lead time using a transit method where the sofas will be routed via distribution centres without actually being taken into store. A critical success factor in achieving these remarkable lead times has been the decision to divorce the sofas from the covers so that they are manufactured and delivered separately and only marry up when they come out of their respective boxes in the customer’s living room. This allows simplicity in the manufacturing process as they are all one colour: white. That is not to say that the product is ‘mass produced’. There is a batch size of one – even for covers - and a product range of over 700 different styles. “ We could make 500 different sofas in a day” says the production manager, “it would be difficult but we could do it!” Normal batch sizes are 25-50. The supply chain is taut with all the components coming from a maximum of 2 hours away. Although some inputs have been imported. For example polypropylene fibre comes from Korea. Most of their suppliers have been with them for 10 years and they try to develop long relationships rather than shopping around. The policy is to stay with the same supplier whilst negotiating prices on a rolling basis. They cooperate closely with their suppliers, both on the design of new products and in coordinating inbound logistics. They also help their suppliers with the purchase of raw materials. For example they import plywood from Russia and the Baltic states at cheaper prices than their supplier can achieve. They then sell it to the supplier before buying the components back and assembling them. Labour in Poland is cheap when compared to Western Europe standards but not by global standards. A factory worker is paid Zl 2000 per month (£330) gross or Zl 1200 net (£198). The Polish working week is constrained by law to 40 hours and the trend is downwards. The factory works 2 x 8 hour shifts; 0600 to 1400 and 1400 to 2200 hours. They acknowledge that Poland can no longer compete with the Far East on price. “We feel the yellow breath on our backs!” as they say. The deduction is that they must compete on the efficiency of their logistics and the service they are able to give in terms of short lead times and small minimum order quantities, as well as quality. CIMIR has just appointed a quality manager and they have 2 quality control inspectors. They are implementing a TQM program and hope to have ISO 9000 accreditation next year. The business process is as designed as far as possible on JIT ‘pull not push’ lines. CIMIR has full visibility of IKEA forecasts and inventory holdings and they have developed their own forecasting model based on trend analysis. Components arrive in exact quantities, pre-cut in the case of wooden components and sometimes foam as well; although fabric purchasing is not possible on a JIT basis. It is noticeable in the in-bound storage area that the components destined for IKEA products are efficiently packaged to take up the least space on the shelves. There is no barcoding as yet and the scheduling is still done manually but the goal is to have a fully computerized enterprise resource planning system (ERP). The shop floor is laid out in cells rather than on a process flow basis. Teams of 5-6 people assemble one complete sofa frame at a time from its parts. This is a conscious decision to give teams ownership and pride in their work. The individuals are all multi-skilled and enjoy greater variety of tasks than in a conveyor belt process. They have tried kanbans without much success but are keen to try again. The frames are then moved into the upholstery shop where again it is a cellular layout. Teams fit the foam padding and the covers and wrap, pack and barcode the products for onward dispatch. Special fire resistant foam is used for products destined for the British market. The whole factory is conspicuous for its lack of work in progress, scrap or buffer stocks. The complete cycle is well under 24 hours and most sofas go out the same day. The warehouse at the back of the factory is set up to load straight onto either trains or lorries. Video cameras look straight into the containers to check on the loading for damage or smuggling. The containers are then sealed. Barcoding facilitates computerized recording of outgoing loads. In a small office in the corner clerks work on IKEA’s ECIS system to ensure that the documentation is correct for customs clearance. In the design workshop CIMIR’s designers are working with a team from IKEA in Sweden, including a freelance designer, on a prototype for an IKEA competition to supply a new range regionally. They will be up against manufacturers in other countries but IKEA’s Warsaw office is helping them with their bid. CIMIR has benefited from IKEA’s advice, particularly on logistics, and this spread of best practice has enabled them to break into a number of new markets serving customers other than IKEA on a make-to-order basis. Supplier Support TA Poland will continue to act as the regional eyes and ears on the ground acting as the interface between IOS and the supplier. The purchaser will be responsible for regular reviews of the supply contract. The technical staff will help with continuous improvements on the design. The business support section will give advice on IT and logistics. And the IKEA transport manager will book all transport rather than the supplier, unless the supplier is able to extract the same terms. That achieves maximum purchase leverage on hauliers and the best possible price for the movement of goods by road or rail. Lead times Great emphasis is put on the ordering and distribution methods. IKEA’s suppliers are categorised according to the lead time that they work on. IKEA’s policy is to try to shorten lead times gradually. IKEA staff refer to the supplier ladder. A supplier may start to supply goods on either a long warning fixed time delivery basis or a call-off >4+4 basis, in other words he will be given over 4 weeks notice of a 4 week window in which he must deliver the goods. IKEA will then help the supplier to develop his business processes to the point where he can progress to call off 4+4. Call offs are time based methods and once the supply chain is functioning smoothly the supplier will progress to an order driven method: Order Point Distribution Centre (OPDC) at progressively shorter lead times, from weeks down to days, with the manufacture and delivery of goods being triggered by orders. Once a supplier is able to achieve this they explore the possibilities of cutting the distribution link out of the chain so that retail stores deal directly with factories (Vendor Managed Inventory or VMI) perhaps with goods bypassing the distribution centres altogether and going direct to retail stores, or going via distribution centres but only on a transit basis so that there is not time for them to be booked in and out of the warehouse. This is supply chain management in its purest form. All links in the chain work together to shorten the cycle time and cut out logistical costs so that products reach the customer at the lowest possible price. The progression up the ladder is gradual and reached by agreement with suppliers. The speed imperative has to be balanced against the dependability of supply and the maintenance of high percentage availability of the product in the stores. It is an IKEA mantra that customers cannot buy products if they are not available on the shelves. The Supplier Benefits The degree of support is impressive. The manufacturer acknowledges that the margins he earns from the products he sells to IKEA are far lower than from other customers but the support he receives and the nature of the relationship he has with IKEA far outweigh this disadvantage. This includes: Contractual Trust. He knows that he will always be paid within 30 days. He knows that in all probability IKEA will stick with him and that, if for any reason the relationship or a product is discontinued, he will not be disadvantaged and any stock in the pipeline will be bought from him. Product Life Cycles. IKEA tries to keep product life cycles as long as possible. Typically they range from 3 years out to 20 years. This helps manufacturers to plan for the long term. Investment. If he has an opportunity to generate extra capacity that will allow him to manufacture products more cheaply for IKEA they may assist with credits to allow him to pay for the plant now and pay IKEA back with his goods later. If he goes to a bank IKEA may help him to gain a loan by guaranteeing a certain level of future business. Focus on profit rather than volumes or margins. In his sales negotiations with the IKEA purchasers he will be dealing with people who understand his business, particularly the cost drivers. Whilst this could be viewed as a disadvantage when it comes to price negotiations, it means that the IKEA traders will work with him to lower his costs so that they can buy at an acceptable price and he can sell at an acceptable profit. This contrasts with the ‘poker playing’ ‘take it or leave it’ approach that characterises many such negotiations in the industry. Ultimately IKEA want to keep the same suppliers for a long time so that they can develop them and to avoid the expense of starting new relationships with suppliers. Technical advice. IKEA staff are on hand to give advice on a number of aspects of the business from the layout and flow on the factory floor to the design of packaging. This allows the supplier to develop distinctive competences in, for example, the application of veneers and lacquers. IT. The supplier will be linked to ECIS, IKEA’s own system. This will allow him to have total transparency of the supply chain so that he can see IKEA sales forecasts and view inventory levels in distribution centres and stores. This helps him to anticipate orders. Upstream, the system facilitates JIT from his sub-suppliers. As the system becomes more refined additional benefits are coming on-stream such as a worldwide trading domain for IKEA partners to allow them to find the cheapest sources of raw materials and components. Logistics. IKEA has a strong logistics competence that it spreads to its suppliers. This comes partly in the form of advice. The IKEA logisticians will work through every element to find the most cost effective option from the packaging, through the filling rate of containers to the route and choice of transport system. It also comes in the form of a railhead, if it is viable, that gives a cost reduction of around €10/m3 for all goods leaving the factory. From a supplier’s perspective a solid relationship with IKEA gives his operation a critical mass and the development of expertise and ‘best practice’ that can be put to good use in winning business from other customers. The Purchaser Perspective IKEA’s commitment to an HR policy that gives its managers a broad training is a contributory factor to the effectiveness of its purchasers. The purchaser will have gained valuable experience in other areas, such as supplier support, that gives him a powerful insight into the cost drivers in the price equation. However, his brief is not to focus exclusively on price but on the future potential of supply relationships and the generation of capacity. If price is a problem he will work with the supplier to reduce the costs rather than looking for a different supplier. This is the essential difference between IKEA’s approach and many others in the industry. The Design Perspective IKEA’s commitment to design is illustrated by the fact that the company’s biography of its founder Ingvar Kamprad is entitled Leading By Design1. It is core to the company’s philosophy that they should design products that are functional, simple, well made and ‘cheerful’ with a distinctive IKEA image and at a price that everyone can afford. This means a commitment to design that not only concentrates on aesthetics but also on economy of effort in materials, assembly, storage and transport. IKEA is an exemplar of ‘lean design’. Designers have to understand the whole supply chain process and tailor their products accordingly. The integrated project team (IPT) approach ensures that all these aspects are covered. And the internal market ensures that prototypes from aspirant supply chains are rigorously tested through the manufacturing and logistics phases of production. The Logistics Perspective The Logistics Manager and the Transport Manager run logistics audits of their suppliers together to identify bottlenecks and improve processes. In TA Poland there is a clear structural distinction between transport and logistics. The essential difference is that transport deals with the present and logistics deals with the future. Interestingly the Army makes the same distinction. The Transport Manager deals with the physical movement of goods and the actual booking of carriers. The Logistics Manager focuses on continuous improvement and the progression of suppliers up the supplier ladder. He will search for new ideas to smooth the flow of goods through hub and spoke systems using best sources of rail or road options. He will try to put railheads into factories and warehouses where possible to give an alternate option to road transport. A comparison of the two transport systems in Poland is shown below: Road Rail €19/m3 to Sweden Faster Less Reliable Eco-unfriendly 80 m3 capacity per lorry €9/m3 to Sweden Slower More Reliable Eco-friendly 200 m3 capacity per waggon Smart logistics at IKEA also includes a very rigorous analysis of the way products are packaged – in the famous flat-pack boxes – and then loaded into containers. Damage in transit is kept to a minimum by strict guidelines and templates for loading. Photographs of damage incidents are taken and lessons learnt and disseminated. It is not uncommon to see video cameras at IKEA suppliers’ factories monitoring the loading of containers (and ensuring that there is no smuggling of illegal cargoes out of Poland). 1 Leading by Design The IKEA Story by Bertil Torekull Harper Collins 1998. IKEA apply the SCM doctrine to picking. There is acknowledgement that the task of picking items from shelves to make up orders has to be done somewhere in the supply chain. They analyze the respective efficiencies in the suppliers’ warehouses and the distribution centre warehouses before making a decision. The development of highly organized hub-and-spoke distribution systems allows minimum order quantities to be kept low. It is possible for a carton, rather than a pallet or a container, to be dispatched from the factory to the distribution centre where loads are then consolidated before being transmitted as containers to destinations around the globe. The Quality Perspective It is a tenet of the IKEA creed that they do not chase after quality for its own sake. Their products are not over-engineered to give a greater finish than the customer requires. Nevertheless quality is taken very seriously and the whole supply chain participates. Their definition of quality is that the product must first be available in the store and secondly it must match up to the customer’s expectations: it must be complete, free from defects and easy to assemble. Returns to stores are analyzed and each product is carefully monitored. TA Poland then runs Project OCTOPUS. This entails a team made up of people from all parts of the supply chain, TA Poland staff as well as suppliers, going to IKEA stores, possibly overseas, and carrying out rigorous inspection of the products there. When they find defects they then track back to see where in the supply chain they have occurred and how they can be prevented from happening again. In this way problems with damage in transit or poor factory quality control are discovered and put right. Quality is also assured by the frequent interaction between TA Poland staff and their suppliers. Purchasers often go into factories and carry out inspections of IKEA products being made there. Questions 1. Product flow structure is described as the network structure for sourcing, manufacturing, and distribution across the supply chain. Since inventory is necessary in the system, supply chain members may keep a disproportionate amount of inventory. When decisions are made to rationalize the supply chain network, it is necessary to determine where the inventory should be held to maximize total supply chain efficiency and effectiveness. Inventory represents a large percentage of a manufacturing firm’s investments in assets and a much larger percentage of the assets for wholesalers and retailers. What are the implications of this for managing inventories in the supply chain? 2 Do you agree with idea that in the future the nature of competition will not be company against company, but supply chain against supply chain? What if the company share the same supplier with competitors, or your supplier is also your competitor ( for example: Wal-mart and Goodyear, Goodyear sells tires to Wal-Mart but also sells tiers by itself ) Do you agree that the Supply Chain Management in Poland is the best answer for Asian’s competitors? 3 As Logistics and Product Development are only part of Supply Chain Management, What future improvements you could suggest (see picture below) for IKEA? As a CEO of company what information from your suppliers and customers you would like to know? What information you would be likely to share with them? 4 Based on your knowledge describe what the terms logistics and supply chain management mean to you. How are logistics and supply chain management similar and/or different? What difficulties would you expect to encounter when trying to implement supply chain management?