Pavlov, Ivan (1992) - Department of Psychology

advertisement

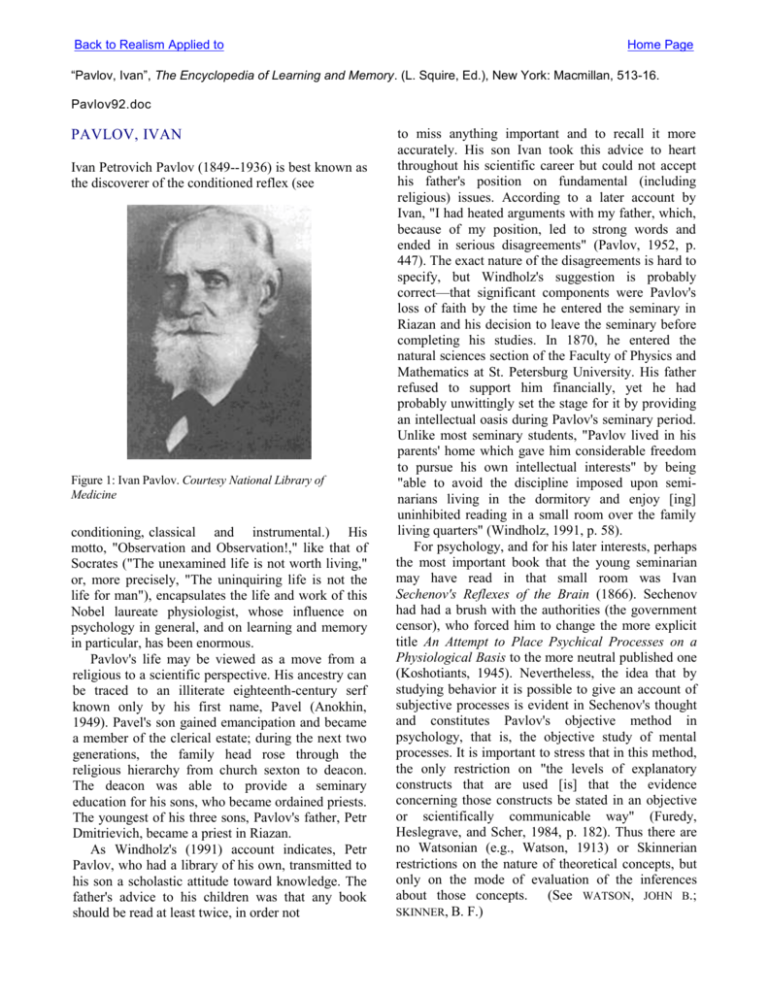

Back to Realism Applied to Home Page “Pavlov, Ivan”, The Encyclopedia of Learning and Memory. (L. Squire, Ed.), New York: Macmillan, 513-16. Pavlov92.doc PAVLOV, IVAN Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1849--1936) is best known as the discoverer of the conditioned reflex (see Figure 1: Ivan Pavlov. Courtesy National Library of Medicine conditioning, classical and instrumental.) His motto, "Observation and Observation!," like that of Socrates ("The unexamined life is not worth living," or, more precisely, "The uninquiring life is not the life for man"), encapsulates the life and work of this Nobel laureate physiologist, whose influence on psychology in general, and on learning and memory in particular, has been enormous. Pavlov's life may be viewed as a move from a religious to a scientific perspective. His ancestry can be traced to an illiterate eighteenth-century serf known only by his first name, Pavel (Anokhin, 1949). Pavel's son gained emancipation and became a member of the clerical estate; during the next two generations, the family head rose through the religious hierarchy from church sexton to deacon. The deacon was able to provide a seminary education for his sons, who became ordained priests. The youngest of his three sons, Pavlov's father, Petr Dmitrievich, became a priest in Riazan. As Windholz's (1991) account indicates, Petr Pavlov, who had a library of his own, transmitted to his son a scholastic attitude toward knowledge. The father's advice to his children was that any book should be read at least twice, in order not to miss anything important and to recall it more accurately. His son Ivan took this advice to heart throughout his scientific career but could not accept his father's position on fundamental (including religious) issues. According to a later account by Ivan, "I had heated arguments with my father, which, because of my position, led to strong words and ended in serious disagreements" (Pavlov, 1952, p. 447). The exact nature of the disagreements is hard to specify, but Windholz's suggestion is probably correct—that significant components were Pavlov's loss of faith by the time he entered the seminary in Riazan and his decision to leave the seminary before completing his studies. In 1870, he entered the natural sciences section of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics at St. Petersburg University. His father refused to support him financially, yet he had probably unwittingly set the stage for it by providing an intellectual oasis during Pavlov's seminary period. Unlike most seminary students, "Pavlov lived in his parents' home which gave him considerable freedom to pursue his own intellectual interests" by being "able to avoid the discipline imposed upon seminarians living in the dormitory and enjoy [ing] uninhibited reading in a small room over the family living quarters" (Windholz, 1991, p. 58). For psychology, and for his later interests, perhaps the most important book that the young seminarian may have read in that small room was Ivan Sechenov's Reflexes of the Brain (1866). Sechenov had had a brush with the authorities (the government censor), who forced him to change the more explicit title An Attempt to Place Psychical Processes on a Physiological Basis to the more neutral published one (Koshotiants, 1945). Nevertheless, the idea that by studying behavior it is possible to give an account of subjective processes is evident in Sechenov's thought and constitutes Pavlov's objective method in psychology, that is, the objective study of mental processes. It is important to stress that in this method, the only restriction on "the levels of explanatory constructs that are used [is] that the evidence concerning those constructs be stated in an objective or scientifically communicable way" (Furedy, Heslegrave, and Scher, 1984, p. 182). Thus there are no Watsonian (e.g., Watson, 1913) or Skinnerian restrictions on the nature of theoretical concepts, but only on the mode of evaluation of the inferences about those concepts. (See WATSON, JOHN B.; SKINNER, B. F.) 514 Pavlov, Ivan Like Sechenov, Pavlov was a revolutionary thinker who, however, was able to deal with authority without either surrendering on vital points or being forced to oppose at the cost of personal ruin. An early instance of this flexibility is that a seminary inspector stated on a written certificate at the end of Pavlov's period of study that "thoughts contrary to the Christian religion ... I never noticed in him" (cited in Windholz, 1991, p. 63), well after Pavlov's religious arguments with his father. Much later, after he had achieved the pinnacle of scientific status for his work on the physiology of digestion (the Nobel Prize, 1904), and had then turned to the study of the "psychic" salivary (digestive) reflex (i.e., Pavlovian conditioning), he was able to maintain an active laboratory throughout the reign of Stalin, a considerable testament to his political skills. Yet Pavlov also showed great courage in challenging authority. Horsley Gantt, a young American scientist who was a visiting member of Pavlov's laboratory in the 1920s, recounts that in 1926 the minister of education and head of the department that supported Pavlov's laboratory came on a site visit, but Pavlov refused even to meet with him, much less show him his laboratory. His stated reason was that he disapproved of the minister's recent book, The ABC of Communism (Gantt, 1991, p. 68). The fact that Pavlov's laboratory survived and thrived following this piece of incredible political insolence suggests both his intellectual integrity and his skill in knowing just how far he could go in challenging authority. He shared with Socrates and other great thinkers the passion for inquiry and the world of the mind, but unlike Socrates he retained the practical skills necessary to survive in the political world. One mark of Pavlov's fame is that he is one of the handful of modern thinkers whose name is used adjectivally to describe concepts. Pavlovian concepts in psychology are widely referred to and may be classified in three areas, the last of which is the most relevant to learning and memory. The first area is that of popular psychology, wherein the term Pavlovian response refers to automatic, nonreflective, reflexlike reactions. In this vein, the brainwashing activities of the Chinese and the North Koreans in the 1950s were considered to be "Pavlovian," and much of orthodox Marxist writings in psychology during the same period in the Soviet Union paid lip service to "Pavlovian principles." Of general scientific interest for personality theory is the Pavlovian notion of differing strengths in the nervous system, a concept that arose from Pavlov's study of experimental neurosis occurring from the breakdown of conditional discrimination in dogs. In the West, Eysenck's work on extraversion and introversion draws heavily on these Pavlovian concepts. Detailed analysis of this psychological (and physiological) theorizing is not relevant here, but it is worth noting that the theoretical ideas and concepts involved are quite complex and go well beyond the observable data that Watson (1913) argued were the only proper subject matter of psychology. For the psychology of learning, however, Pavlov's most important concept is indubitably that of the conditioned reflex, which is a form of learning resulting from "classical" or "Pavlovian" conditioning. In classical conditioning, a stimulus (e.g., food) that unconditionally elicits the to-be-learned response (e.g., salivation, the unconditioned response or UR) is paired with a "neutral" stimulus (e.g., bell) that, conditional on being paired repeatedly with the unconditioned stimulus (US), comes to elicit salivation as the conditioned reflex or response (CR). In Pavlov's view, the classical conditioning preparation was contrary to "subjective psychology [which] held that saliva flowed because the dog wished to receive a choice bit of meat" (Grigorian, 1974, p. 433). This sort of cognitive and purposive formulation is akin to interpretations of the Skinnerbox bar press, instrumental conditioning in terms of bar-pressing being emitted by the rat "in order to get the food." The conditioned reflex concept was of considerable theoretical importance in psychology during the heyday of LEARNING THEORY in the 1940s and 1950s. During this period, learning theory was viewed as primary, as illustrated by the dictum that learning theory is behavior theory. And classical conditioning was considered to be the basic building block that underlay all forms of learning and behavior. The dominant learning-theory approach was that of the stimulus-response (S-R) theorists like C. L. HULL (1943) and K. W. SPENCE (1956), and an important concern was the theoretical attempt to account for apparently cognitive, stimulus-stimulus behavior in terms of S-R principles, that is, through the learning of responses only. The fractional anticipatory goal response construct was the S-R theoretical concept of choice, and both Hull (1931) and Spence (1956) specifically asserted that this theoretical response mechanism was learned through classical conditioning. Pavlov, Ian In addition to such theoretical usage of classical conditioning, there was widespread empirical research directed at observing the acquisition and extinction of the CR as a phenomenon in its own right, although the dominant preparation under study was not the animal salivary one but the human eyelid conditioning experiment. In this preparation, an air puff to the eye served as the US, a blink as the UR and CR, and (usually) a tone as the CS (conditional stimulus). Consistent with the prevailing S-R emphasis, eyelid conditioning was found to be critically determined by various independent variable manipulations and dependent variable measurements. Concerning independent variables, the most important one was the period between CS and US onsets, the CS-US interval. The optimal CS-US interval was slightly less than 0.5 second, and CS-US intervals of 2 seconds or greater produced no conditioning at all (i.e., no increase in CS-elicited blinks as a function of paired CS-US trials). The CSelicited response latency measurement was also found to be crucial: shorter-latency blinks (occurring within 150 milliseconds following CS onset) were found to decrease rather than increase as a function of repeated CS-US pairings, so that only longerlatency blinks (the frequency of occurrence of which did increase as a function of CS-US pairings) were classified as CRs. The decline of the S-R approach in psychology and the "paradigm shift" to the cognitive, S-S approach resulted in a radical shift in theoretical perspective on Pavlovian conditioning. According to its most famous modern exponent, Pavlovian conditioning is "now described as the learning of relations among events so as to allow the organism to represent its environment" (Rescorla, 1988, p. 151). It is interesting to compare this cognitive ("relations between events") and purposive ("so as to allow") formulation with the "subjective psychology" account cited above, which Pavlov opposed. At a more empirical level, the 1970s and 1980s also saw the virtual abandonment of the eyelid preparation as a means of studying the Pavlovian (response) conditioning phenomenon. An improved form of the preparation (the rabbit nictitating membrane preparation developed in the 1960s) has been employed, but predominantly as a technique to study the effects of physiological manipulations rather than the phenomenon of conditioning itself. Consideration of the CS-US interval has essentially disappeared, to the extent that, in the currently dominant Rescorla-Wagner (1972) model of Pavlovian conditioning, the CS-US interval 515 does not appear as a parameter. Considering the fact that, as indicated above, the CS-US interval is crucial in preparations such as eyelid conditioning, this omission may seem strange. However, most of the evidence and experimental work of current cognitive S-S Pavlovian conditioners is based on preparations where conditioning is not measured directly through assessing the CR, but indirectly through assessing the effect of the CS on some instrumental indicator behavior, as in the conditioned emotional response preparation. Such indicator-behavior preparations are more likely to suggest that Pavlovian conditioning is the learning of "relations between events" (i.e., cognitive, S-S learning of CS/US contingency) rather than the learning of (conditional) responding (i.e., the CR) to the CS. It is also interesting to note that not only during the current cognitive S-S phase, but also during the earlier S-R phase, of Western experimental psychology, no body of systematic reports of Pavlovian dog salivary conditioning emerged in the journal literature. Pavlov's methods were based on single case studies, and the dependent variable differences were reported quasi-anecdotally rather than with specified reliability in terms of the rules of statistical inference. Furthermore, his preparation is extremely difficult to work with. For example, the typical subject requires some 3 months of adaptation to the holding harness before the food reliably elicits salivation rather than competing struggling behavior. Still, the Pavlovian emphasis on using behavior as the objectively observed dependent variable has been retained by both the S-R experimentalists and their cognitive, S-S oriented successors. The Pavlovian emphasis on observation has been carried on as an intellectual tradition by the Pavlovian Society. This international organization was founded in the United States in 1955 by Horsley Gantt, who, as noted above, worked in Pavlov's laboratory in the 1920s. The official journal of this society was first Conditional Reflex, then Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science, and, most recently (1991), Integrative Behavioral and Physiological Science. Although few members of this interdisciplinary group (whose backgrounds and interests range from singlecell physiology to psychoanalysis) specialize in classical-conditioning research, the common ground is provided by the society's motto ("Observation and Observation"). To them it means that whatever the differences may be between favored theoretical positions, the 516 Pavlov, Ivan issues should be debated in the light of the observed evidence. REFERENCES Anokhin, P. K. (1949). Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. Zhizn, deiatel'nost i nauchnaia shkola Moscow and Leningrad: Izdatel'stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR. Furedy, J. J., Heslegrave, R. J., and Scher, H. (1984). Psychophysiological and physiological aspects of Twave amplitude in the objective study of behavior. Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science 19, 182-194. Gantt, W. H. (1991). Ideas are the golden coins of science. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science 26, 68-73. Grigorian, N. A. (1974). Pavlov, Ivan Petrovich. In Dictionary of scientific biography, vol. 10, pp. 431—435. New York: Scribner. Hull, C. L. (1931). Goal attraction and directing ideas conceived as habit phenomena. Psychological Review 38, 487-505. -------- (1943). Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory. New York: Appleton-CenturyCrofts. Koshotiants, K. S. (1950). /. M. Sechenov. Moscow. Izdatel'stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR. Pavlov, I. P. (1952). Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (avtobiografiia). In his Polnoe sobranie sochinenii, vol. 6. Moscow and Leningrad: Akademii Nauk SSSR. Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian conditioning: It's not what you think it is. American Psychologist 43, 151— 160. Rescorla, R. A., and Wagner, A. R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In A. H. Black and W. F. Prokasy, eds., Classical conditioning vol. 2, Current theory and research New York: AppletonCentury-Crofts. Sechenov, I. (1866). Refleksy golovnogo mozga St. Petersburg: Tipographiia A. Golovachova. Spence, K. W. (1956). Behavior theory and conditioning. New Haven: Yale University Press. Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review 20, 158-177. Windholz, G. (1991). I. P. Pavlov as a youth. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science 26, 51—67. John J. Furedy