Interdisciplinary PLCs 1 Developing the Framework for an

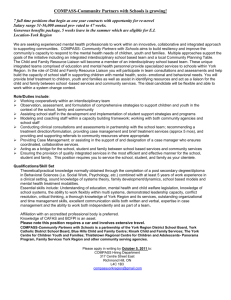

advertisement

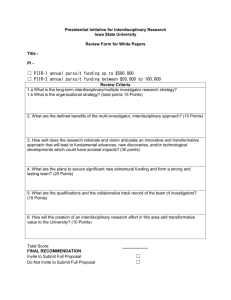

Running head: Interdisciplinary PLCs 1 Developing the Framework for an Interdisciplinary PLC Lando Carter MTSU Author Note Lando Carter, Doctoral Student, College of Education, Middle Tennessee State University, at Murfreesboro, Tennessee. This project was completed with help from the administration and the teachers in the math department at Central Magnet School in Murfreesboro, TN. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lando Carter, Doctoral Student, College of Education, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132. Email: jlc3s@mtmail.mtsu.edu Interdisciplinary PLCs 2 Abstract Successful collaborative teaming begins with the cornerstone beliefs of DuFour, DuFour, and Eaker’s (2008) landmark PLC theories; however, the goal of this project is to transcend the traditional boundaries of a PLC. Thus, the goal is to build the groundwork for an interdisciplinary PLC team at Central Magnet School, one that combines the minds of English and math teachers to yield strategies that help achieve Lezotte and Snyder’s (2011) pinnacle goal: high levels of learning for all. Keywords: collaboration, interdisciplinary, PLC, teamwork, school improvement Interdisciplinary PLCs 3 Literature Review The theories for this project arise from many educational avenues. Graziano and Lori Navarette (2012), for example, champion the idea of co-teaching to achieve high levels of learning for all students in a school: “There are many benefits of co-teaching including opportunities to vary content presentation, individualize instruction, scaffold learning experiences, and monitor students’ understanding. Co-teaching in its most effective form can promote equitable learning opportunities for all students” (p. 109). Indeed, Graziano and Navarette’s concepts mirror that of DuFour, DuFour, and Eaker (2008) as well as Lezotte and Snyder’s (2011) work. Specifically, Graziano and Navarette (2012) argue that preparation to coteach must happen first. The project at Central was rooted in this notion as well. Next, the aforesaid authors state that readiness to collaborate and co-teach must be determined, followed by clarifying roles and responsibilities, expectations, planned meeting times, and pledging to establish a clear line of effective communication (p. 110). Harris (2010) has helped fuel this project as well. He calls for a three tier approach to sustaining collaboration. According to Harris, a deep commitment to collaboration must occur. Secondly, a pledge to act on the plan and mobilize the faculty must begin. Lastly, collaboration will exponentially grow by being adaptive when challenges emerge (p. 25). The similarities to the seminal voices in PLC theory are paramount; however, theses scholars have yet step further to create interdisciplinary PLC teams. At Central, Kyle Prince and Iliana Taylor—both high performing math teachers—have worked diligently with the English department to ensure that even gifted students fight to reach new heights. Cook and Faulkner (2010) believe that common planning time between interdisciplinary teachers can open the floodgates to a new level of teaming within a school. DuFour, DuFour, and Interdisciplinary PLCs 4 Eaker (2008) advocate for common planning time for PLC teams, but this is almost exclusively designed for grade or subject level teachers. This collaboration plan at Central aims to change both the technical and cultural elements Muhammad (2009) details in Transforming School Culture. Changing teachers’ schedules, a technical change that is a challenge in itself, can be daunting; however, Muhammad warns that just allotting time for such collaboration will not yield a true cultural change within the school (p. 15-16). Furthermore, Cook and Faulkner’s (2010) study reveals that their interdisciplinary middle school teachers met at least four times per week (p. 2). At their school, one that has earned the prestigious Kentucky School to Watch award, teachers meet regularly by grade level and in interdisciplinary teams as well (p. 6). They have built an exemplary model for constant collaboration in various team configurations: “While priorities for teams varied from week to week, depending on the individual issues teams were addressing or the timing of the school year, student growth and behavior and teacher morale were consistently emphasized” (p. 7). This type of collaboration time during the school day is indeed easier at the middle school level, but with a dedication to substantive cultural change, it can be successful at the high school level. Magiera (et al., 2006) unanimously agrees that time for co-planning during the school day must exist to ensure that teachers can reflect on classroom lessons and retool their plans to meet the immediate needs of students (p. 7). Lezotte and Synder (2002) would certainly agree that a system of just in time intervention—one of the seven correlates of highly effective schools theory— provides instantaneous opportunities to meet students exactly where they are in their learning (p. 34). This project at Central, on the other hand, took place almost exclusively outside of the normal school day, which delayed addressing students’ needs. Common planning time for this new PLC team, as a result, is indispensable to future success. Interdisciplinary PLCs 5 Finally, Pella’s (2011) lesson study model echoes Twadell’s (2008) astute commentary on the Japanese collaborative teaming approach. Frequent team meetings, co-development of lessons, observations of lesson delivery, debriefing sessions, and studying student performance frame the lesson study model (Pella p. 110). Furthermore, Twadell (2008) believes that “teachers engaged in lesson study maintain a laser-like focus on student learning” (p. 115). However, the lesson study model normally operates around grade level teams or subject teams. This project at Central will cement the foundation for lesson study to occur in a interdisciplinary manner. Method Participants The entire math department at Central participated in this collaboration project; however, two math teachers became integral parts of the project, and these two teachers—Kyle Prince and Iliana Taylor—have made this project possible by donating weeks of their time and energy. 104 students in Mr. Prince’s Algebra II classes also participated in this study and responded in writing, which provided mounds of qualitative data. Materials The following survey was administered to the aforesaid Alegbra II students after a coteaching/collaborative lesson in earl March during a 90 minute block period (all questions allowed for students to respond in writing): 1. How did you feel about the unit circle concept before and after the game? 2. Did the game help you see or understand the unit circle in a different way? Briefly explain why or why not. Interdisciplinary PLCs 6 Procedure The basis of this collaboration study began by examining Central’s school improvement plan, which revealed a small but important achievement gap between economically disadvantaged students and non-economically disadvantaged students. This 1.5% gap prompted further examination, and this closer look at the problem started with Central’s RTI math period, led by Iliana Taylor. After spending weeks in RTI observing and communicating with Mrs. Taylor, it was clear that Algebra II students were struggling with the Unit Circle concept (see appendix B). Once the problem was located, Mr. Prince was consulted because his students were regularly reporting to RTI for remediation on this concept. Mr. Prince then collaborated with the English department to conjure up new ways to approach this strategy. A collaborative, coteaching mindset immediately emerged, and an innovative game that addresses the unit circle in a new way was born. After weeks of teaming, Mr. Prince and I tested the lesson together on his 2nd period Algebra II class (he taught the lesson solo for the other periods). The lesson began with a prequiz warm-up for the unit circle. Students were given four minutes to complete the circle. This was a formative, ungraded assessment. Next, students were broken into bracketed teams to complete against each other in the unit circle game (see pictures below). When the game was finished, students were then sent back to their seats to take the actual unit circle quiz and complete the student survey displayed above. Interdisciplinary planning and co-teaching then lead to deep PLC style discussions and debriefing between an English teacher and two math teachers. Interdisciplinary PLCs 7 Results Qualitative data gleaned from the student survey revealed that students overwhelmingly positive results. Here are sample responses from the student survey: 1. How did you feel about the unit circle concept before and after the game? Before the game, I felt like I hadn't fully mastered the unit circle, afterwards I actually finished the circle in under 4 minutes for the first time. I was doing pretty well on the unit circle before the game, but the game helped me with the sin and cos. I started looking at the "triangles". I did get my best time of 3:10 after the game though. I was completely lost before playing the game. After the game, the idea began to make more sense. After going back and studying and playing a little more, the concept will sink in. 2. Did the game help you see or understand the unit circle in a different way? Briefly explain why or why not. Yes, it helped me understand the sin/cos better using the triangle thingy. It helped with sin and cos because when you're up against someone and you have a limited time, it's more pressure to answer faster. By looking at the triangles you could decide whether it was the smaller or bigger triangle and decide which number to go with based on that. Yes it did. Seeing a picture of the circle flash up and having to imagine all of the degrees and radians on the picture really helped be start to visualize. Interdisciplinary PLCs 8 The positive responses to the survey questions also correlate with the strong unit circle quiz grades from all of Mr. Prince’s classes: Class Period: Class Average Score: 1st 96% 2nd 95% 4th 95% 5th 97% 6th 96% 7th 96% Discussion The results from the student survey and unit circle quiz are encouraging. What this means is that interdisciplinary PLC teams can work at Central, and now the next step is to take this notion to the administration to garner the support needed to make the necessary technical and cultural changes. First, common planning time must be considered; however, this will indeed be a challenge because Central currently dedicates common planning to teachers of the same grade level. The goal is not to supersede that approach but simply add to it. Once regular collaboration time between the disciplines is established, sustained collaboration can occur at Central and hopefully close achievement gaps and ensure high levels of learning for all students. Ideally, this teaming study will extend to various departments and team configurations at Central. Perhaps a mixture of English and science can be the next approach. The key to making interdisciplinary PLCs a reality at Central is achieving wholesale belief in such an idea, one that is undoubtedly worth the time and effort. In the end, if only a handful of students transcend to new levels of learning, this approach will be valuable. Interdisciplinary PLCs 9 Reflection Mr. Prince, Mrs. Taylor, and I have built a wonderful relationship because of this project. A strong pipeline of communication now exists between English and math, something that certainly did not exist before. We now have a bond built on trust, and that coveted bond that countless administrators and teachers seek was forged through vulnerability. I took a risk and decided to direct both of my projects this semester down a completely unfamiliar pathway. The results have left me spellbound. Mr. Prince and I plan on moving forward with the idea of interdisciplinary PLC teams and carving out a new model for other high schools to use. Interdisciplinary PLCs 10 References Cook, C. M., & Faulkner, S.A. (2010). The use of common planning time: A case study of two Kentucky schools to watch. Research in Middle Level Education, 34 (2), 1-12. DuFour, R. [Richard], DuFour R. [Rebecca], & Eaker, R. (2008). Revisiting professional learning communities at work: New insights for improving schools. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press. Graziano, K. J., & Navarrete, L. A. (2012). Co-teaching in a teacher education classroom: Collaboration, compromise, and creativity. Issues in Teacher Education, 21 (1), 109-126. Harris, M. (2010). Interdisciplinary strategy and collaboration: A case study of American research universities. Journal of Research Administration, 41 (1), 22-34. Lezotte, L.W., & Snyder, K.T. (2011). What effective schools do: Re-envisioning the correlates. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press. Magiera, K., Lawrence-Brown, D., Bloomquist, K., Foster, C., Figueroa, A., Glatz, K., Heppeler, D., . . . Rodriguez, P. (2006). On the road to more collaborative teaching: One school’s experience. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 2 (5), 1-12. Muhammad, A. (2009). Transforming school culture. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press. Pella, S. (2011). A situative perspective on developing writing pedagogy in a teacher professional learning community. Teacher Education Quarterly, 4, 107-125. Twadell, E. (2008). Instructional improvement from the inside out: Lesson study at work. The collaborative teacher: Working together as a professional learning community (pp. 97-117). Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press. Interdisciplinary PLCs 11 Appendix A Interdisciplinary PLCs 12 Interdisciplinary PLCs 13 Interdisciplinary PLCs 14 Interdisciplinary PLCs 15 Appendix B