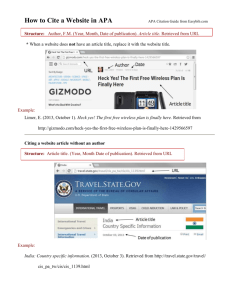

Figure 1 - UNESCO

advertisement

Figure 1. Traylor’s Global Culture of Human Rights Advocacy (Mayring, 2000; Ellington, 1997, Kirk; Fox, 2007). 1. Sharing a sense of Urgency: Implementing Change through Commitment of human rights culture 2. Phase Create a Guiding Vision: Educators and activist leadership builds community awareness in the workplace and through coalition networking. a2. Phase Create a Guiding Coalition: Tied to Vision. Meaningful as a feature of teleological, social-cognition, human resources structural and political leadership. 3. Develop A Visible Mission of with practical solutions for Human rights violations through addressing the politicization and economic of “border” l-cognition, human resources structural and political leadership. ethos 4. Communicate the Change Vision: Dialog through community effort nationally and globally, e.g., Beijing Conference (1995) Vision is realized: Strategic Objective I.1. school culture. 5. Empower Broad-based Action: Promote awareness through education 7. Consolidate Gains and Produce More Change: Organize and delegate. Understand adversary. 6. Promote and protect the human rights of women, through the full implementation of human rights laws. Demand accountability through representation 8. Anchor New Approaches in the Culture: amalgamation of three international women’s organizations as part of a united front: the Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW), the United Nations Development Fund for Women (U.N.IFEM), and the Office of the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Gender Issues (OSAGI). Beckner, W. (2004). Ethics for educational leaders. New York: Allyn & Bacon. Retrieved May 11, 2007, from https://mycampus.phoenix.edu/secure/resource/resource.asp Berg, G. A., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (2003, September-October). Mission possible? Enabling good work in higher education. Change, 35(5), 40. Retrieved May 18, 2007, from http://www.apollolibrary.com/Library/ERR/ElectronicReserveReadings.aspx http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book36.html Fox, J., (2007). Amnesty International honors Mexican advocate for women and children's rights. El Reportero. Vol. 17, Edition 12 May 23 - 31, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2007, from http://www.elreporterosf.com/editions/?q=node Kirk, G., Zoglin, K., Totani, Y, and Cartwright Traylor, J. (2005). Women and War: A Critical Discourse. Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law & Justice, Vol. 20, p321-368, 48p; Retrieved June 6, 2007, from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdf?vid=4&hid=113&sid=a5a9c8c9-4ca2-42baafed-875c0d24e547%40sessionmgr107 Stefkovich. J. A., & O’Brien, M. G. (2004). Best interests of the student: an ethical model. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(2), 197-241.Retrieved May 23, 2007, from http://proquest.umi.com/pqdlink? Traylor, J. C., (Winter 2006/2007). Gender equality and women’s empowerment – Progress at the United Nations. Human Rights Advocates. Vol. 48. Retrieved January 6, 2007, from http://www.humanrightsadvocates.org/images/HRA_Vol48.pdf Stefkovich. and O’Brien outlined the myriad of theories and conflicting attitudes that have sociopolitical and legal implications as a facet of the ethics to ensure basic rights: Table 1. Basic Human Rights (Stefkovich. & O’Brien 2004) Basic Human Rights 1. Natural rights granted to all human beings 2. Universal rights recognized by the United Nations, e.g., Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989); 3. Rights guaranteed by law, specifically those articulated under US Constitution's Bill of Rights. 4. Certain fundamental rights as universal despite the fact that some countries such as the USA have not recognized them (Bitensky, 1992; Levesque, 1996). 5. US Constitution rights including freedom of religion, free speech, privacy, due process, and freedom from unlawful discrimination, i.e. equality. 6. Right to dignity; respect for all individuals and protection from humiliation. 7. Right to an education 8. Right to be free from bodily harm.