Online Resources for Chapter 01 Chapter 1 Word Document

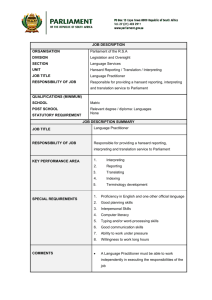

advertisement

CHAPTER 1: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH LEGAL SYSTEM AND ITS SOURCES Accessing Acts of Parliament and Delegated Legislation (page 10). For a detailed description of delegated legislation, see the House of Commons Information Office Factsheet, Legislation Series L7, ‘Statutory Instruments’ at www.parliament.uk/factsheets. Acts of Parliament and statutory instruments are available online at the Statute Law Database run by the Ministry of Justice at www.statutelaw.gov.uk and on the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/acts.htm. Both sites contain legislation from 1988 to the present with an increasing back catalogue of earlier legislation being added. For access to the current version of all legislation in force including all amendments, you will have to use one of the legal databases referred to in the research chapter, such as Westlaw or LexisLibrary. In order to find prospective legislation in the form of Bills currently before Parliament (and Bills from recent sessions), go to www.parliament.uk/business/bills-and-legislation.cfm. Explanation of the Belmarsh Case (page 12). A v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2005] 2 AC 68. This case concerned the detention without charge or trial of nine foreign nationals (the appellants) at Belmarsh high security prison ‘on suspicion of being international terrorists who posed a risk to national security’ (Baroness Hale at paragraph 222). Under Article 5 of the ECHR: ‘Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be deprived of his liberty save in the following cases and in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law…’ The relevant ground in the Belmarsh case was ‘(f) the lawful arrest or detention of a person…against whom action is being taken with a view to deportation or extradition.’ Under the power delegated by section 14(1) and (6) of the HRA 1998 the Home Secretary had made an order in the form of a statutory instrument (the Human Rights Act 1998 (Designated Derogation) Order 2001) derogating from Article 5(1) of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR). The appellants had been lawfully arrested and detained as suspected terrorists but they could not be deported to their home countries because of the risk that they would be tortured or executed; deportation under such circumstances would itself be a violation of Article 3 of the ECHR and other international conventions prohibiting torture. The appellants claimed that their continuing detention, without charge, trial, or deportation, under s.23 of the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, was in breach of their right to personal liberty guaranteed by Article 5 of the ECHR. They argued that the United Kingdom’s derogation from Article 5 was discriminatory, disproportionate and unjustified. Nine Law Lords heard the appeal (normally only five sit, exceptionally seven) A majority of eight (Lord Hoffmann dissenting) agreed that the risks of terrorism were sufficient to constitute a public emergency threatening the life of the nation as required by Article 15 for derogation from an ECHR obligation. However, seven of that majority held that the interference with the appellants’ right to liberty was unjustified because the 2001 Derogation Order and the detention without trial on suspicion of being international terrorists under section 23 of the 2001 Act applied to non-nationals only, not to British nationals equally suspected of posing a risk to the state as terrorists. Under Article 14 of the ECHR: ‘The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property birth or other status.’There had been no derogation from Article 14 and the continuing detention of non-national terrorist suspects without trial when national terrorist suspects were not so detained was a violation of Article 14 in conjunction with Article 5 that was neither justifiable nor proportionate. A majority of eight Law Lords (Lord Walker dissenting) therefore ordered that the Derogation Order should be quashed and declared that section 23 of the 2001 Act (permitting the detention without deportation of suspected international terrorists) was incompatible with Articles 5 and 14 of the ECHR. Explanation of the Literal Rule (page 17). Fisher v Bell [1961] 1 QB 394 Under s 1(1) of the Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959, ‘Any person who manufactures, sells or hires or offers for sale or hire …’ a flick-knife was guilty of an offence and liable to imprisonment and a fine. Bell, the defendant, had a shop in Bristol with a window display that included a flick-knife advertised as ‘Ejector Knife – 4s’. Bell was charged under s 1(1) with offering for sale a flick knife. He was found not guilty at Bristol magistrates’ court. The prosecutor appealed to the Divisional Court of the Queen’s Bench Division but the appeal was unsuccessful. Despite recognising ‘that most lay people … would be inclined to the view that to say that if a knife was displayed in a window like that with a price attached to it was not offering it for sale was just nonsense’ (Lord Parker CJ at page 399), the Divisional Court held unanimously that no offence had been committed. Under contract law such a window display is ‘merely an invitation to treat’ not an ‘offer for sale’ and that ‘is clearly the general law of the country’ (Lord Parker CJ at page 399). The words ‘offer for sale’ must be given their technical legal meaning unless Parliament stipulated otherwise (for example, by extending the offence to include exposing for sale as was the case in other legislation). The failure to use words defining the offence which covered the display of flick-knives may well have been a drafting error. Nevertheless, it would be unconstitutional for the courts to second-guess the legislature and fill in likely gaps in the wording of an Act. To do so, as Lord Simonds had put it in Magor and St Mellons Rural District Council v Newport Corporation [1952] AC 189 at page 191, would be ‘a naked usurpation of the legislative function under the thin guise of interpretation’. Explanation of the Golden Rule (page 17). R v Allen (1872) LR1 CCR 367 In this case the accused, Allen, was charged with offence of bigamy under s57 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 which provides that: ‘whosoever being married shall marry any other person during the life of his former husband or wife shall be guilty’ of bigamy. Allen had married Harriet Crouch in 1871 while still the husband of another woman he had married in 1867. However, Harriet Crouch was the niece of a former wife of Allen who had died in 1866. Even if Allen had been unmarried, his marriage to Crouch would have been void under separate legislation prohibiting marriage between categories of close relations. Allen claimed that he could not have committed bigamy as he had not in fact married Crouch. His argument was unsuccessful. As Cockburn CJ pointed out, to hold that the words ‘shall marry’ require the accused to enter into a legal marriage would be clearly absurd as no bigamous marriage can be legal. This would make the offence of bigamy impossible to commit. The words ‘shall marry another person’ should therefore be read as meaning ‘shall go through the form and ceremony of marriage with another person’. What are Explanatory Notes? (page 18). R (Westminster City Council) v National Asylum Support Services [2002] 1 WLR 2956 Lord Steyn: ‘In so far as the Explanatory Notes cast light on the objective setting or contextual scene of the statute, and the mischief at which it is aimed, such materials are therefore always admissible aids to construction. They may be admitted for what logical value they have. Used for this purpose Explanatory Notes will sometimes be more informative and valuable than reports of the Law Commission or advisory committees, Government green or white papers, and the like. After all, the connection of Explanatory Notes with the shape of the proposed legislation is closer than pre-parliamentary aids which in principle are already treated as admissible: see Cross, Statutory Interpretation, 3rd edn (1995), pp 160–161.’ Explanation of the Mischief Rule (page 19). Royal College of Nursing v Department of Health and Social Security [1981] AC 800 Until the Abortion Act 1967 it was a criminal offence to have, carry out or assist an abortion under ss58 and 59 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861. The only exceptions were if an abortion was necessary to save the life of the pregnant woman or where the continuation of the pregnancy would have extremely severe physical or psychological consequences. Section 1(1) of the Abortion Act 1967 provides that no offence is committed under the law relating to abortion ‘when a pregnancy is terminated by a registered medical practitioner’ (and other requirements of s 1 are satisfied). In the years after the Act came into force surgical abortion became largely obsolete and most abortions were carried out by nurses through medical induction of labour. The nurses would act on a doctor’s instructions but the main procedure was not carried out in the doctor’s presence. Since nurses are not ‘registered medical practitioners’ the Royal College of Nursing disputed the Department of Health and Social Security’s advice to the effect that the new procedure was lawful under the Act. This controversial case about a controversial issue turned on the interpretation of s1(1). Interestingly, of the nine judges who heard the case (through the High Court, Court of Appeal and House of Lords) a majority of five found for the Royal College and concluded that the new procedure was unlawful as nurses, not doctors, were terminating pregnancy by medical induction. Decisively, however, three of the minority of four judges who held that the new procedure was lawful formed a majority of three in the House of Lords. Of that majority Lord Diplock used the mischief rule to support his interpretation of the section. Although unimpressed by the drafting of the Act, Lord Diplock (at pages 825, 827 and 828–9) argues that the Act clearly contemplated a team effort in which abortions, like many other medical procedures, would be carried out by nurses and others acting on the instructions and under the supervision of doctors who had made the abortion decision: ‘Whatever may be the technical imperfections of its draftsmanship, however, its purpose in my view becomes clear if one starts by considering what was the state of the law relating to abortion before the passing of the Act, what was the mischief that required amendment, and in what respect was the existing law unclear … the wording and structure of the section are far from elegant, but the policy of the Act, it seems to me, is clear. There are two aspects to it: the first is to broaden the grounds upon which abortions may be lawfully obtained; the second is to ensure that the abortion is carried out with all proper skill and in hygienic conditions … In my opinion in the context of the Act, what it requires is that a registered medical practitioner, whom I will refer to as a doctor, should accept responsibility for all stages of the treatment for the termination of the pregnancy. The particular method to be used should be decided by the doctor in charge of the treatment for termination of the pregnancy, he should carry out any physical acts, forming part of the treatment, that in accordance with accepted medical practice are done only by qualified medical practitioners, and should give specific instructions as to the carrying out of such parts of the treatment as in accordance with accepted medical practice are carried out by nurses or other members of the hospital staff without medical qualifications. To each of them, the doctor, or his substitute, should be available to be consulted or called on for assistance from beginning to end of the treatment. In other words, the doctor need not do everything with his own hands; the requirements of the subsection are satisfied when the treatment for termination of a pregnancy is one prescribed by a registered medical practitioner carried out in accordance with his directions and of which a registered medical practitioner remains in charge throughout.’ Explanation of Hansard (page 20). Hansard is the name given to the official report of debates and proceedings in both Houses of Parliament. Parliament once prohibited all reporting of its proceedings. By the late 18th century, press attacks from individual MPs and public dissent persuaded Parliament to change its stance and in 1803 the House of Commons passed a resolution giving the press the right to enter the public gallery. William Cobbett immediately began to publish Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register. In 1812 publication was taken over by his assistant Thomas Hansard who, in 1829, changed the title to Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates. The name Hansard continued and was later officially adopted by Parliament as the edited verbatim report of Parliamentary debates. The same did not go for what was said in parliamentary debate and committees during the passage of the legislation. The courts consistently asserted the strict exclusionary rule: Hansard – the official daily report of proceedings in both Houses of Parliament – could not be used as a guide to the meaning of statutory provisions. This was for constitutional reasons and because of the unreliability of statements made in the course of parliamentary debate. The legitimate uses and limits of background material (“travaux préparatoires” or “preparatory works”) in statutory interpretation prior to the decision in Pepper v Hart were considered in the two House of Lords judgments which follow. (i) The use of preparatory materials and the exclusionary rule: before Pepper v Hart [1993] AC 59. Black-Clawson International Ltd v Papierwerke Waldhof-Aschaffenburg Aktiengesellschaft [1975] AC 591 In a legal dispute between an English and a German company, the issue arose as to whether a judgment by a German court in favour of the German company was conclusive and binding on the English courts. The substance of the dispute is unimportant for present purposes. What matters is that it turned on the interpretation of a statute – s 8 of the Foreign Judgments (Reciprocal Enforcement) Act 1933 – and, in deciding on the correct interpretation, the House of Lords’ views on the use of background materials and what was out of bounds. The background material in this case was the report of the Foreign Judgments (Reciprocal Enforcement) Committee 1932 (Cmd 4213). Lord Reid, at pages 614–15, stated clearly that the report could be used to identify the state of the law prior to the Act and the mischief that the Act was intended to remedy and no more. The court cannot look for guidance from the intentions expressed in such a report any more than it can seek the intentions of the legislature by consulting Hansard. Lord Wilberforce agreed (at pages 629–30) as did Lord Diplock (at pages 637-9) providing the following explanation: ‘The acceptance of the rule of law as a constitutional principle requires that a citizen, before committing himself to any course of action, should be able to know in advance what are the legal consequences that will flow from it. Where those consequences are regulated by a statute the source of that knowledge is what the statute says. In construing it the court must give effect to what the words of the statute would be reasonably understood to mean by those whose conduct it regulates. That any or all of the individual members of the two Houses of the Parliament that passed it may have thought the words bore a different meaning cannot affect the matter. Parliament, under our constitution, is sovereign only in respect of what it expresses by the words used in the legislation it has passed. This is not to say that where those words are not clear and unambiguous in themselves but are fairly susceptible of more than one meaning, the court, for the purpose of resolving – though not of inventing – an ambiguity, may not pay regard to authoritative statements that were matters of public knowledge at the time the Act was passed as to what were regarded as deficiencies in that branch of the existing law with which the Act deals. Where such statements are made in official reports commissioned by government, laid before Parliament and published, they clearly fall within this category and may be used to resolve the ambiguity in favour of a meaning which will result in correcting those deficiencies in preference to some alternative meaning that will leave the deficiencies uncorrected. The justification of this use of such reports as an aid to the construction of the words used in the statute is that knowledge of their contents may be taken to be shared by those whose conduct the statute regulates and would influence their understanding of the meaning of ambiguous enacting words.’ The established line against the use of Hansard was taken yet more emphatically by the House of Lords in Davis v Johnson in the face of a challenge by Lord Denning in the Court of Appeal (at 272–83). Lords Diplock and Scarman and Viscount Dilhorne in particular reasserted that official reports could be consulted to identify the mischief which the legislation is intended to remedy. However, such reports do not have the formal interpretative status of travaux préparatoires in the context of European legislation, while under no circumstances should parliamentary debates be referred to; they are simply unreliable guides to the meaning of what is enacted. According to Lord Scarman at pages 349–50: ‘There are two good reasons why the courts should refuse to have regard to what is said in Parliament or by Ministers as aids to the interpretation of a statute. First, such material is an unreliable guide to the meaning of what is enacted. It promotes confusion, not clarity. The cut and thrust of debate and the pressures of executive responsibility, essential features of open and responsible government, are not always conducive to a clear and unbiased explanation of the meaning of statutory language. And the volume of Parliamentary and ministerial utterances can confuse by its very size. Secondly, counsel are not permitted to refer to Hansard in argument. So long as this rule is maintained by Parliament (it is not the creation of the judges), it must be wrong for the judge to make any judicial use of proceedings in Parliament for the purposes of interpreting statutes.’ (ii) Pepper v Hart [1993] AC 59: a new approach to Hansard In Pepper v Hart Lord Browne-Wilkinson reviewed the reasons given for the exclusionary rule in a series of cases and summarised them as follows ([1993] AC 59 at page 633): ‘[T]he reasons put forward for the present rule are first, that it preserves the constitutional proprieties leaving Parliament to legislate in words and the courts (not Parliamentary speakers), to construe the meaning of the words finally enacted; second, the practical difficulty of the expense of researching parliamentary material which would arise if the material could be looked at; third, the need for the citizen to have access to a known defined text which regulates his legal rights; fourth, the improbability of finding helpful guidance from Hansard.’ Because of the constitutional significance of the case, Pepper v Hart was decided by a committee of seven law lords instead of the usual five (more recently the House of Lords has started to sit as a bench of nine judges in cases of major constitutional significance; no doubt the new Supreme Court will follow suit). By a majority of six to one the House of Lords finally held that judges could consult Hansard as an aid to statutory interpretation. This move must be seen as the clearest indication that the courts have moved decisively from a primarily literal, formalist approach to interpretation towards a more realistic purposive approach. According to Lord Browne-Wilkinson (at page 635), with whom Lords Ackner, Bridge, Keith and Oliver expressly agreed: ‘Given the purposive approach to construction now adopted by the courts in order to give effect to the true intentions of the legislature, the fine distinctions between looking for the mischief and looking for the intention in using words to provide the remedy are technical and inappropriate. Clear and unambiguous statements made by Ministers in Parliament are as much the background to the enactment of legislation as white papers and Parliamentary reports.’ The House of Lords was clear that the occasions when a court could turn to Hansard to solve a problem of statutory interpretation would be few and far between. Pepper v Hart itself concerned an ambiguity in the Finance Act 1976 as to the income tax status of certain benefits in kind. There had been a clear statement by the minister responsible for promoting the Bill to the effect that the benefits in question would be treated in a way that favoured the taxpayer. The possibility of using Hansard as an aid to interpretation would be restricted to just such (rare) circumstances: ‘I therefore reach the conclusion, subject to any question of Parliamentary privilege, that the exclusionary rule should be relaxed so as to permit reference to Parliamentary materials where (a) legislation is ambiguous or obscure, or leads to an absurdity; (b) the material relied upon consists of one or more statements by a Minister or other promoter of the Bill together if necessary with such other Parliamentary material as is necessary to understand such statements and their effect; (c) the statements relied upon are clear.’ (Lord Browne-Wilkinson at page 640) (iii) Pepper v Hart: the aftermath In a number cases, including Wilson v First County Trust Ltd (No 2) [2004] 1 AC 816 and Robinson v Secretary of State for Northern Ireland [2002] UKHL 32, the Law Lords have criticised the excessive use of Hansard since Pepper v Hart. The following comments by Lord Hoffmann in Robinson v Secretary of State for Northern Ireland [2002] UKHL 32 demonstrate our highest court’s concern that the strict requirements laid down by the last case had not been observed: ‘40. …. References to Hansard are now fairly frequently included in argument and beneath those references there must lie a large spoil heap of material which has been mined in the course of research without yielding anything worthy even of a submission. In R v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions, Ex p Spath Holme Ltd [2001] 2 AC 349, 391–392, 398–399, 407–408 and 413, and again in R v A (No 2) [2002] 1 AC 45, 79 attempts were made by several of your Lordships to reduce the flow by insisting that the conditions for admissibility must be strictly complied with. I am not sure that it is sufficiently understood that it will very rare indeed for an Act of Parliament to be construed by the courts as meaning something different from what it would be understood to mean by a member of the public who was aware of all the material forming the background to its enactment but who was not privy to what had been said by individual members (including Ministers) during the debates in one or other House of Parliament. And if such a situation should arise, the House may have to consider the conceptual and constitutional difficulties which are discussed by my noble and learned friend Lord Steyn in his Hart Lecture ((2001) 21 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 59) and were not in my view fully answered in Pepper v Hart.’ Hansard should only be referred to where the strict requirements laid down in Pepper v Hart are satisfied. Even then the House of Lords has frequently been sceptical about whether a ministerial statement can be relied on as an indication of what a statute means. Activity: Find a spare piece of paper and jot down a paragraph for each of the following questions: (1) What was the position before Pepper v Hart? (2) What are the conditions set by Pepper v Hart? (3) What was the aftermath of Pepper v Hart? (4) What impact has Pepper v Hart had on English law? ‘Distinguishing’ Precedents (page 28). (a) Distinguishing When a solicitor or barrister presents his or her client’s case, or a judge explains how he has reached his or her decision, they have to consider the relevant precedents and argue that they apply to the present case or that they are distinguishable from one another. Activity: Can you ‘distinguish’? Look at the two sentences below. Can you see why they should be distinguished (i.e. ‘set apart’) from one another? ‘We judge in favour of the respondent. He clearly provided express and lucid notice that he was going to withdraw the offer after three weeks. He was not liable after that period passed. Case dismissed.’ ‘We judge in favour of the respondent. He was not liable after the “offer” time period passed. He wrote to the claimant revoking his offer. It was cancelled, He was not liable after this time.’ Answer: (b) Distinguishing obiter from ratio. Activity: Obiters and ratios are sometimes muddled up by students. Find a spare piece of paper and jot down why the first quote below is a ratio, and the second quote below is obiter. Do you know the formal difference between the two? ‘The defendant believed that he was defending himself against a vicious attack. He saw a knife and assumed the worst. He legally defended himself against the perpetrator.’ ‘When a defendant sees a knife, or any sharp object, flash in the moonlight, and a perpetrator running towards him, fully masked and unidentifiable, it is inevitable that the defendant will wish to defend his own person if the perpetrator should catch up. There is no time to take stock. One acts on instinct.’ Statutory Interpretation (general online materials for Chapter 1). Task 1: Judges interpret statutes in several ways. Answer this question: what is the ‘literal rule’? Task 2: 23(a) A sample of the Road Traffic Act 1988 is placed below. What kind of behaviour is s.192(1) trying to eradicate/criminalise? Section 192(1): In this act…“road” in relation to England and Wales, means any highway and any other road to which the public has access, and includes bridges over which a road passes. Task 3: Read the facts from Cutter v Eagle Star Insurance Co Ltd [1998] 4 All E.R. 417 (below). ‘On 21 July 1991 the plaintiff, Stuart Richard Cutter, was injured by an explosion in a parked car in which he was a passenger in the Great Hall car park, Tunbridge Wells. He brought an action against the driver, Kristian Pennial, for negligence and on 29 October 1992 he obtained judgment in the Tunbridge Wells County Court for personal injury, loss and damage for £8,547.33, together with costs of £4,105.86. The defendants denied that the car was being used on a road at the time of the incident. On 21 September 1995 Mr. William Kee, sitting as a deputy circuit judge in the Tunbridge Wells County Court, dismissed the action holding that the accident had not occurred on a road as defined in section 192 of the Act of 1988.’ The courts applied the wording of the statute literally to the case facts. What did this mean for the defendant? Task 4: What is the ‘golden rule’? Task 5: Below is a sample from s.57 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861. What kind of behaviour does it make illegal? Section 57: Whosoever, being married, shall marry any other person during the life of the former husband or wife, whether the second marriage shall have taken place in England or Ireland or elsewhere, shall be guilty of felony, and being convicted thereof shall be liable [...] to be kept in penal servitude for any term not exceeding seven years Task 6: In R v Allen (1872) LR 1 CCR 367 a man was charged with bigamy. Why could s57 (above) not be applied ‘literally’ to a bigamist using the literal rule? Task 7: What is the ‘mischief rule’? Task 8: Below is a section of the Street Offences Act 1959: S1(1): ‘It shall be an offence for a common prostitute to loiter or solicit in a street or public place for the purpose of prostitution.’ This section was applied in Smith v Hughes (1960). Prostitutes were tapping on windows and standing on balconies. Why would a judge not want to apply the literal rule to this case? Task 9: Lord Parker in Smith v Hughes (1960) said the following: ‘Everybody knows that this was an Act to enable people to walk along without being molested or solicited by common prostitutes… it can matter little whether the prostitute is standing in the doorway or on a balcony…’ What rule is he applying and how does that rule ensure justice? Finding the ratio in a decision (general online materials for Chapter 1). Activity: Tilly has plagiarized her assignment, and the lecturer’s decision is below. Your job is to find the ratio (i.e. the decision) in the lecturer’s judgment. “Tilly plagiarised her entire assignment - everything was copied from the Parliamentary website. I called her and she wasn’t home. Her mother hung up on me! Therefore, as a result of the plagiarism combined with the bad study skills, Tilly will have to re-take her assignment. She has no one to blame but herself. Next year, her study skills should be much better.” Write the ratio in here:

![R (Evans) and another v Attorney General [2015] UKSC 21](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006598240_1-a7706c52e14434f0fee64b71e28c9736-300x300.png)