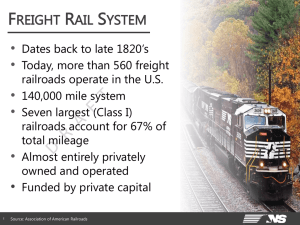

7. Landside Transpor.. - Institute for Research on World

advertisement