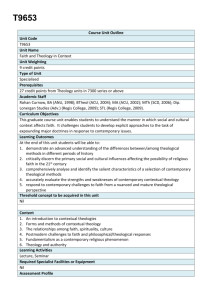

this module

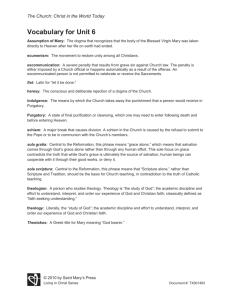

advertisement