Click For Artifact #1

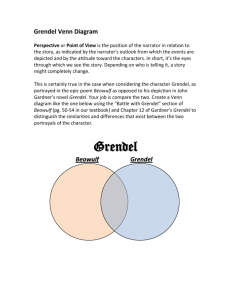

advertisement

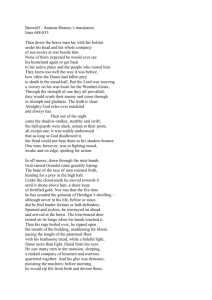

Fatima Chishti English 397 05-02-08 Evolution of Hybridity within the Postcolonial Monster Human fear of the unknown and the displaced is a fear that has been evolving through centuries. The inability to classify and categorize a being stupefies mankind and then forces further misclassification and disunity. In the medieval context, one who could not produce pure identity lost his strongest weapon, a weapon which would safeguard his acceptance into society. Displacement of identity meant displacement within society, but further, the fear of difference caused a heightened level of panic which inspired belief in and creation of the monstrous. According to Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, a prominent scholar on monstrosity, “The monster is difference made flesh, come to dwell among us. In its function as dialectical Other or third-term supplement, the monster is an incorporation of the outside, the Beyond- all of those loci that are rhetorically placed as distant and distinct but originate Within” (Cohen, Monster Culture, 7). Cohen argues that monstrosity’s origins are from our own inability to accept differences. The label of the monstrous comes from a desire to disenfranchise what is unlike us. Cohen continues, “Any kind of alterity can be inscribed across (constructed through) the monstrous body, but for the most part monstrous difference tends to be cultural, political, racial, economic, sexual” (Cohen, Monster Culture, 7). The ideology that monsters are not necessarily inhuman, but instead are a creation of human intolerance towards diversity, becomes a postcolonial matter. Within postcolonialism, the concept of monsters then becomes one of hybridity. Rather than being an “other” which is separate from the “self”, monsters become more of a reflection of difference within a body of sameness. The evolution of monstrosity from one of the oldest introductions to monsters, the epic poem, Beowulf, to present day adaptations of this tale shows a time-lapse of what it meant and what it now means to be classified as a hybrid. In a sense, hybridity makes postcolonial of the medieval. As the definition of hybridity evolves with the evolution of the Beowulf tale, an increased parallel with postcolonialism occurs. By looking at the ways hybridity is defined through a postcolonial lens, the goal of the paper is to trace the ways hybridity functions socially and politically with the evolution of the monsters (Grendel and his mother) from Beowulf through Gardner’s Grendel, McTiernan’s, The Thirteenth Warrior, and Zemeckis’s, Beowulf . This paper questions happens when we are “outside” the medieval audience and the creation of monsters occurs in the social setting of today, one which is fairly disconnected from the medieval world. Who becomes monstrous and how hybridity functions changes along with the evolution of this classic tale. With it remaking in a postcolonial society, the monster evolves to fit our society’s fears. Defining hybridity in the postcolonial sense becomes crucial to our understanding of how monsters have evolved over time. This is because the “other” has come a long way since its 1000 year old release in Beowulf to how identity is classified, formed, and maintained today. Cohen quotes Robert Young’s definition of hybridity in his essay, “Hybrids, Monsters, Borderlands: The Bodies of Gerald of Wales” for a definition of the hybrid, “difference and sameness in apparently impossible simultaneity” (Cohen, Hybrids, 85). He continues, “If the medieval touches the postcolonial exactly at the point of hybridity, this conjunction reveals both a startling consonance and a productive dissonance….medieval hybridity is, to paraphrase Bhabha, ‘the same but not quite.’” (Cohen, Hybrids, 85). For Cohen, hybridity becomes a conflicting convergence of identity. He quotes Young again in saying hybridity is, “contra fusion and disjunction…as well as fusion and assimilation” (Cohen, Hybridity, 1). Hybridity in this sense is not containable within boundaries of a single identity. It is neither combining with nor completely going against a society- almost as if in limbo. Homogeneity is simply not happening through hybridization, there is ‘a joining of differences that cannot simply harmonize’ (Cohen, Hybridity, 2). This definition of hybridity becomes a surface definition. As we delve deeper into the causes and effects of monstrosity, this definition will add on layers of complication, but for now, it is the inability to be wholly one identity. The conflict of becoming part of and removed from the Anglo-Saxon society function simultaneously as an identity for our Grendel family in the original Beowulf. In the epic poem of Beowulf, the monstrosity that immerges from Grendel is that of a beast derived from man: Grendel was the name of this grim demon… in misery among the banished monsters, Cain’s clan, whom the Creator had outlawed ‘ and condemned as outcasts, For the killing of Abel… and out of the curse of his exile there sprang ogres and elves and evil phantoms and the giants too who strove with God. (Beowulf, 102-113) While it is clear that a descendent of Cain would ultimately place Grendel in the lineage of man, it appears that an outcast breeds an outcast. However, it is not simply that Grendel is under a grandfather clause of ostracism; Grendel’s exiled lineage has provoked society into viewing him as one who is inseparable from beasts and creatures that are evil rather than as a part of man whom he is genetically linked to. The jump from man to monster comes instantly. It appears that one must eternally pay the price for his ancestors’ mistakes. This unavoidable classification leads to isolation and demonization of the ‘other’. Though human, Grendel is pushed away from that part of himself and instead he is pushed into something that the people can no longer pretend to identify with: Every nail, claw-scale and spur, every spike and welt on the hand of that heathen brute was like barbed steel. Everybody said there was no honed iron hard enough to pierce him through, no time proofed blade that could cut his brutal blood caked claw. (Beowulf, 983-89) Grendel is no longer identified as being in the same flesh as man; instead, he has become almost machinelike in his impenetrability. Hybridity is then being formed into Grendel’s identity by Anglo-Saxon. They are placing him as a rejected state of man, but closer to inhuman; further, they have morphed him into a being more machine than man, one beyond human penetration. According to Cohen’s Monster Culture: The monster’s body quite literally incorporates fear, desire, anxiety, and fantasy… giving them life and an uncanny independence. The monstrous body is pure culture. A construct and a projection…the monster signifies something other than itself. (Cohen, Monster Culture, 4) With Cohen’s theory in place, we can assume that the Grendel character in Beowulf then becomes a representation of the culture and time period he is in. The signification of religious ‘othering’ branches Grendel away from the goodness of man, but also, the industrialized strength symbolizing the ideal man for war encapsulates the admiration of brute strength. Ruth Waterhouse in her essay, Beowulf as Palimpsest, writes: The mysterious dimension of Grendel is a crucial part of how he is presented in Beowulf. There is no overt close description of him, though his eyes, his hands, and of course his head are fore grounded in the discourse, and though he seems to be huge…his size is left vague. From a twentieth-century stance, an awareness of this lack of specific description is as much as indication of our current expectations as it is a comment on the contemporary society. (Waterhouse, 33) Waterhouse brings the original poem into a modern context, questioning the description of the monster and suggesting that without a clear cut depiction, our imaginations do not believe in his monstrosity. A depiction of Grendel’s crimes gives us the explanation of strength: …Suddenly then The God-cursed brute was creating havoc: Greedy and grim, he grabbed thirty men From their resting places and rushed to his lair, Flushed up and inflamed from the raid, Blundering back with the butchered corpses. (Beowulf, 120-125). Grendel’s monstrosity is seen through his actions, though physical description is scarce. For a medieval text, this depiction of strength, much like the machine-like depiction of his impenetrability, would suffice in drawing attention to horror. However, as Waterhouse suggests, it does not seem brutal enough for today’s readers or audiences. Cohen writes on this phenomenon of being unmoved by monsters, “Aurally received narratives work no differently; no matter how unsettling the description of the giant, no matter how many anabaptized children and hapless knights he devours King Arthur will ultimately destroy him. The audience knows how the genre works” (Cohen, Monster Culture, 17). Cohen and Waterhouse both describe the phenomenon of today’s world where description must be more intricate, and even then, it is unlikely that description of action alone will force us to view something as monstrous. However, for the culture and time period, this idea of being a man-machine, grabbing men like a monster, yet having the sense to bring back the corpses shows a hybrid of mentality. While 20th century audiences may not fear Grendel because of the lack of physical description, the fact remains clear; there is an understanding present within the monster to know how to pursue these people time and again. Grendel’s 12 year reign is evidence to this power. As the story of Beowulf moves to a more modern version, shifts in the ideology of the people and likewise, the representation of monsters, vastly differs from the original text. John Gardner takes the epic ballad and transforms it into a retelling of the story from the perspective of Grendel. Published in 1971, the story is an existential view of monstrosity within society. Grendel going from antagonist to more plausible protagonist shifts his physical representation from his original début. In Gardner’s, Grendel, our monster is not described from an outside perspective. This first-monster perspective leaves the reader at the mercy of Grendel to be self reflective and he does not disappoint, “Pointless, ridiculous monster crouched in the shadows, stinking of dead men, murdered children, martyred cows” (Gardner, 6). Though Grendel at times speaks in the third person, all part of this existential crisis, we see his self-deprecation through description. He is calling himself a monster and he doubts his own worth. Looking back at the epic poem, the narrative has shifted tremendously to arrive at this version of the story. The social aspects between the two are entirely different, but before one delves into the social aspect, the description of monsters is what needs to be compared. Even though Grendel has called himself a monster, he bares more similarities to the humans than could have been said for the Beowulf monster. This Grendel gives up snippets of description which make us aware of how close to human he really is. He makes reference to his humanlike body parts such as arms, legs, eyes, face. These fragments of descriptions come as snippets where he will mention his condition as humanly as possible, “My head aches. Morning nails my eyes” (Gardner, 13). Grendel’s complaints are easily relatable to a reader’s everyday life. Therefore, these commonly heard asides make Grendel connected with the reader. We are given these snippets so we can slowly piece together Grendel as we delve deeper into his psyche. Though the Beowulf Grendel cannot be denied some of his human features, what we get in Gardner’s version is weakness: He shook his horns at me, as if scornfully. I trembled. On the ground, on two good feet, I would have been more than a match for the bull, or if not, I could have outrun him. But I was four or five feet up in the air, trapped and weak…he could gore me to death at his leisure in the grass. (Gardner, 20). Gardner’s Grendel becomes a monster who is self conscious and insecure about himself. Opposing the original tale, this Grendel fits Cohen’s explanation of the identity crisis of hybridity, “Hybridity tends to remain a tumultuous, conflicted state, easily roiled by changes in social context” (Cohen, Hybridity, 145). Grendel in this modern novel becomes a physically weaker link, essentially impossible to correlate with monstrosity. Beyond the physical aspects of the differences between the two tales, the definition of hybridity and how it relates to monstrosity must be brought up again in a social context. Cohen’s cultural, political, racial, economic, and sexual differences between hybrids/monsters and the self is an issue that is being tackled in Gardner’s book. Gardner’s monster does not dwell on the physical aspects of his being; what separates him from the others is the way in which he thinks and communicates. The cultural difference that Cohen writes on is what makes this Grendel monstrous. The linguistic challenge Grendel faces added to a slight physical difference exaggerates the physical difference more, hence, labeling him monstrous: I staggered out into the open and up toward the hall with my burden, groaning out, ‘Mercy! Peace!’ The harper broke off, the people screamed…Drunken men rushed me with battle-axes. I sank to my knees, crying ‘Friend! Friend!’ They hacked at me, yipping like dogs (Gardner, 52). The problem is not that Grendel is incapable of communication. He understands the language of the humans, though he does not always understand their ways, however, both the language and the ways of Grendel are misunderstood. There is only one way communication, in that Grendel can understand the people. His adaptation to their language and culture puts him at a moral high ground for understanding, yet he is ostracized for his differences: The sounds were foreign at first, but when I calmed myself, concentrating, I found I understood them: It was my own language, but spoken in a strange way, as if the sound were made my brittle sticks, dried spindles, flaking bits of shale. (Gardner, 38) The linguistic-cultural challenge that Grendel faces poses him as a monster to the community, but the reader understands his plight and immediate sympathy is gained for the monster. Man must then be wrong in that he is not listening carefully enough to the “other.” Monstrosity does not exist until we call on it to exist. What makes Grendel’s hybridity even more transparent is his inability to communicate with his mother, “She’d forgotten all language long ago, or maybe had never known any. I’d never heard her speak to the “other” shapes. (How I myself learned to speak I can’t remember; it was a long, long time ago.)” (Gardner, 28). Grendel is now caught in a realm between man and between monster. He is in the third-space, failing to communicate properly with anyone and therefore, isolating himself as an “other” among those who collectively came to produce him. Grendel even questions this lack of communication, “‘Why can’t I have someone to talk to?…‘The shaper has people to talk to’… ‘Hrothgar has people to talk to.’” (Gardner, 53). Here Grendel is comparing himself to man assuming he deserves communication and equating himself to their species. Grendel questions his inability to communicate and assumes the language and culture of the people as one he should be a part of. He is not isolating himself; he desires inclusion. One of the biggest challenges Grendel faces becomes not only creating an implicit linguistic association between himself and man, but he becomes confused in if he should relate himself to them, “It was confusing and frightening, not in a way I could untangle…the men who fought were nothing to me, except of course that they talked in something akin to my language, which meant that we were, incredibly, related” (Gardner, 36). This becomes the moment of Grendel’s intense hybridic struggle. He slowly integrates himself into their society, passively taking in all of their culture, but eventually he is caught between two beings, “Thus I fled, ridiculous hairy creature torn apart by poetry crawling, whimpering, seaming tears, across the world like a two-headed beast, like mixed-up lamb and kid at the tail of a baffled, indifferent ewe…” (Gardner, 44). Grendel’s very being is caught between the humane and animalistic. He is emotionally suffering with his desire to be a part of the human society. However, his physical appearance and inability to communicate make him a rejected hybrid. From the epic poem, our version of Grendel became one of a hybrid between man and machine. In Gardner’s version, impenetrability is later bestowed upon him by a dragon. Before this curse was put upon him, Grendel was viewed as more fleshy and human like in his actual physical appearance very much equated with nature. He would bleed and feel pain. The mechanical descriptions, however, are not absent from this text. They are instead used to describe the ‘hero’ of the original epic: Staring at his grotesquely muscled shoulders-stooped, naked despite the cold, sleek as the belly of a shark and as rippled with power as the shoulders of a horse…He was dangerous …He talked on. I found myself not listening, merely looking at his mouth, which moved- or so it seemed to me- independent of the words, as if the body of the stranger were a ruse, a disguise for something infinitely more terrible. (Gardner, 155) Grendel’s description of the hero, unnamed though assumed to be Beowulf, is one that is mechanical and cold, much like the original description of Grendel in the epic poem. Beowulf is described as though a hybrid of machine, man, and animal. A role reversal has occurred in Gardner’s novel. Though Grendel equates himself to a hybrid, the people do not see the human side of him. However, Grendel can see the animalistic and inanimate nature of man as more fitting of the definition of hybrid. Cohen writes: Medieval hybridity is an impudent relentlessly embodied phenomenon that brings together in a conflictual, ‘unnatural’ union races (genera) in the medieval sense: not just different kinds of human bodies, with their competing determinations, but geographic, animal, “inanimate” bodies that incarnate heterogeneous histories of colonization inscription, transformation…medieval hybridity is the admixture of categories, traumas, and temporalities that reconfigure what it means to be human. (Cohen, Hybrids, 89) From this definition, we see that Grendel’s depiction of the hero becomes one that encompasses many of the characteristics of medieval hybridity. Though this definition fits with context of medieval hybridity, the text itself is not in the social context of the medieval and therefore, it is fitting for Grendel to be the one labeling the hero as a hybrid. From this text, we get the sensation that hybridity is inherent within all of us, hero and monster, and we are not that different from one another. Hybridity becomes less of a simply physical aspect of man and beast, but a psychological and social state of mind as well. Readers relate more to this Grendel than the mechanical hero, therefore, when this novel’s protagonist claims, “…no wolf was so vicious to other wolves…Now and then some trivial argument would break out, and one of them would kill another one” (Gardner, 32) it is implied that our brutality is beyond that of animals and one that even this hybrid can pick out as revolting. Now that the story of Beowulf is launched in the modern world, the aspects of hybridity and monstrosity have changed as one can note from Gardner’s novel. Cohen’s argument on hybridity passing up physicality and moving to an “othering” of difference related to culture still stands. It becomes more prevalent as this story continues on the path of modernity. Moving to a more modern Beowulf story, hybridity begins to focus even less on the monstrous claws and talons of medieval monsters. As we bridge past with present in this tale, through adaptations of the story in film, there is a necessity to make the film relatable to the people who will be watching it. The oral tradition was adapted to fit society as it was passed down. The story of Beowulf has not changed in that aspect. The retelling of it constantly changes to fit the audience. Hybridity, and its different meanings, therefore, change as well. Cohen writes about hybridity in a postcolonial medieval sense, “‘postcolonial’” stands for a diverse alliance of work that stresses the uneven structure of power that comes into being when cultures meet. Conquest, domination, and injustice are predictable outcomes of such clashes. Innovation, hybridity, and resistance are, however, never far behind” (Cohen, Hybridity, 5). As we move into the film adaptations of the Beowulf legend, these ideas of conquest and domination are worked into the previous definitions of hybridity to make it more easily tied to the postcolonial. Cohen’s definition of postcolonial stems from the concept of power coupled with the clash of cultures and ethnicities. While race was a concept that was present in the medieval world and was linked to ethnic group (Bartlet, 2001), an issue that becomes morphed from the medieval to the modern is the social and political concepts behind monstrosity. Race and ethnicity in postcolonialism ties into ideas of colonizer/colonized. In the original Beowulf text, race becomes linked with, ‘monster-race’ rather than a bastardization of a whole people who are still seen as human. The modern concept of race/culture becomes a driving factor in how we define postcolonialism and how the definition of hybridity changes with the way society views an “other”. Greta Austin in her essay, Marvelous Peoples or Marvelous Races?, writes on the place of race in Anglo-Saxon culture: Race- although a number of alternative definitions could be proposed- has come to refer very frequently to certain broad divisions among humans, divisions which are made on the basis of physical appearance and place of national origin. But the word race seems to have been coined only in the seventeenth century, when it was taken up as a way of classifying the natural world. (Austin, 26-27). While we see the concept of race as broad, it still dives into the idea of “among humans”. Though Grendel is described as a descendent of Cain in the original text, his actions and physical appearance prove other than human. In Gardner’s version, it is never stated what his origins are at all. What then becomes increasing postcolonial is the depiction of the monsters as directly from within us. In McTiernan’s adaptation of a modernized Beowulf, The Thirteenth Warrior, we see the concepts of race and hybridity as it relates to ethnicity among people. Cohen writes, “An indigenous people are represented as primitive, subhuman incomprehensible in order to render the taking of their lands unproblematic” (Cohen, Hybridity, 87). These aspects of the indigenous and primitive are very present in the depiction of the evil ‘Wendols’ that invade the village. One man’s description is as follows: ‘Teeth like a lion, head like a bear, claws that could tear a plank to kindling. They come in the night in the mist always in the darkest like they could see in the black’ - ‘did they walk on two legs or four?’ ‘It seemed they did both- like a thing that was both man and bear. I saw the glow worm though, saw it clear… Slithering this way and that… Spitting as it came’. (The Thirteenth Warrior) When we see the Wendols actually attack, what is shown on the screen is the exact description the man has given us. What is being feared is a monster that is a hybrid of fierce animals. Ruthlessly barbaric in their fighting, depicted as animalistic, however, they remain very capable of human tasks. The fear lies in the possibility that this cross breed of animal and human could have adapted the skills necessary to be in power. Cohen writes on, “connecting medieval colonialist projects of representation to their mimicry and subversion…” (Cohen, Postcolonial, 89). He continues citing an example of fourteenth century history of France, the Grandes Chroniques, where the Saracen army of Cordova employing tactical mimesis, or imitation, to defeat Charlemagne’s cavalry. Cohen writes: Each one had a horned mask, black and frightening, on his head, that made him look like a devil…In his hands, each held two drums together making a terrible noise, so loud and frightening that the horses of our soldiers were terrified. Without reference to the surrounding text, a medieval observer of the minutely rendered scene might not guess that the Saracens are wearing masks, for their caricatured corporeality is wholly consonant with other textual and pictoral representations of Muslims as a monstrous cultural other. (Cohen, Hybrids, 88-89). This racial “othering” and linking together with ideas of monstrosity are explored with The Thirteenth Warrior. As it turns out, mimicry is being utilized by the Wendols in order to give a similar impression of power and monstrosity. Their heads, teeth, and claws come from animal masks and parts, very similar to the ones the Saracens don. The “fire worm” or “glow worm” that is burning down their village, is actually hundreds of men carrying torches. The idea of evil is inherently tied to the monstrous, something beyond humanity, beyond humans. One of the warriors replies upon hearing the “fire worm” is really men, “I would rather prefer a dragon” (The Thirteenth Warrior). The Wendols were thought to be demons by the villagers and warriors before adequate evidence became available to characterize them as humans. Cohen writes on this phenomenon of relating cultural difference to monstrosity, “The monster can embody the abject, such as when the Welsh or the Jews are transfigured into blood-thirsty foes, bereft of humanity. Yet the monster can also offer a body through which can be dreamed the dangerous contours of an identity that refuses assimilation and purity” (Cohen, Hybridity, 6). In the case of the Wendols, the viewers are receiving this outlook of humanity. The monsters are not an alien life form or something beyond humanity, they become indigenous cultures who refuse to conform to “humanity”. As we get closer and closer to the Wendols through the battles the tone and anxiety shifts as Ahmed realizes “It’s a man…It’s a man…It’s a man” (The Thirteenth Warrior). Once the point of humanity is established, a new anxiety and power is realized and established. Ahmed’s fighting gets more ferocious and shows his rage. This anger and dominance seems to come from the realization that he can dominate these people, but also through a new anxiety that it is people who are being barbaric. This leads to an unsettling realization that it is someone from among them who has become monstrous. Once the connection is made that these Wendols are not “monsters” in the physical sense, the power dynamic shifts and a need to colonize and defeat the “other” develops. For the villagers, there is no choice in the matter of whether to invade or not. Through an invasion of the Wendols’ lair, the new characterization comes that these people are a cannibal tribe. Ahmed’s reaction to the cannibalism is, “I was wrong, these are not men” (The Thirteenth Warrior). The immediate desire to disinherit the Wendols as part of a shared race shows the fear of the monstrosity of people. Ahmed’s comment makes one assume that if the Wendols were actually monsters, their actions would be excusable, but their desire to live in a culture that is different, forces a rejection. His comment legitimizes the colonization, violation, and eventual annihilation of their people. Going deep into their lair it is clear that these people have their own society and ruling system. They are warriors and conquerors. They are the racial “other” that now need to be colonized or destroyed because they put a threat on everything we know to be humane and right. The invasion of the Wendol lair is a continuation of the original Beowulf story. The lair of Grendel’s mother was also invaded with a desire to destroy the beast within. However, the difference of invasion lies in the fact that in both the original epic and Gardner’s version the mother came out of lair to defend her son. The attack from Beowulf in those aspects was more of retaliation as well as an assurance that no more attacks would be underway. In The Thirteenth Warrior, the Wendol warriors are invading the land, and nationalistic pride and civic duty come into play, the invasion and penetration of the lair to kill the woman is due to a desire to stop breeding more cannibals and letting this race continue. The warriors could defeat all the men and exterminate the race, but they choose to go after the queen as a symbolic gesture of cutting their leadership from the top and destroying a civilization. They are not eliminating the Wendols as a whole, they could always get a new queen, they are instead colonizing them and forcing them into their world. As long as the cannibal race is able to lose identity through the killing of their queen, there is no point in exterminating a whole class of people. It is more profitable to assert power as a noble and pure race to survivors than to simply destroy a culture. In this way, without a leader, the Wendols are more likely to assimilate into surrounding cultures. Jeffrey Cohen writes on the aspect of the frontier and borderlands in medieval society that is coupled with hybridity: A frontier is a temporal and geographic edge where an “advanced” culture is imagined to meet a distant, primitive world in order to begin the process of making the “new” land and its people learn both their backwardness (the frontier is by definition “undeveloped”) and their marginality (the center of the world is elsewhere, and so new cartography of signification, a new way “to divide the world,” must be disseminated). (Cohen, Hybrids, 95). When the warriors enter the lair of the Wendols they are in fact crossing this borderland into the world of the primitive. The depiction of the Wendols is one of classic savage. They are seen through Gloria Anzaldua’s depiction of what lies beyond at the borderland: Borderlands foster “shifting and multiple identity and integrity,” since they are home to multiple and “bastard” languages; the borderland is a place of masticate of new and impure hybrids, of los astravesados “the squint-eyes, the perverse, the queer, the troublesome the mongrel, the mulato, the half-breed…those who cross over, pass over, or go through the confines of the ‘normal’. (Cohen, Hybrids, 96). As soon as their lair is penetrated, the Wendols are unmasked and viewed from a perspective that contrasts their dominance on the battlefield. The Wendols are without their masks, without their weapons, and without clothing; the classic image of an indigenous/native tribe. Their language appears barbaric and animal like through chanting and their faces are blackened with paint. The penetration and elaborate description of the lair as well as the people is very different from the overpowering of Grendel and his mother from older representations of this story. The depiction of both the Wendols and the place they inhabit is intricate. Immediately the connection for modern audiences is that indigenous people inhabiting areas of the borderlands are a threat to our safety as well as to humanity. Monstrosity comes from these hybrid people, biologically human, but socially barbaric. The place which they inhabit becomes a symbol for Eastern lands and thought separate from the civilized west. The lesson for today’s audiences becomes that colonization of these hybrids is necessary. It is no longer a matter of killing off one or two monsters that may be attacking; it is a matter of killing off a whole life style of the people The final venue in which to look at hybridity is through the modern lens of Zemeckis's Beowulf. Cohen writes, “Mixed ethnic identity is figured as ontologically different because it arises at that border where cultures meet in a violent, “unnatural” coupling” (Cohen, Hybrids, 92). We have reached a new age of the legend of Beowulf, one which recognizes that monstrosity becomes a problem not from the physical or even from the indigenous. Rather, the fear of mixing becomes the greater shame and horror of breeding a mixed race. Cohen continues in Monster Culture: As a vehicle of prohibition, the monster most often arises to enforce the laws exogamy, both the incest taboo and the decrees against interracial sexual mingling…The monster are here, as elsewhere, expedient representations of other cultures, generalized and demonized to enforce a strict notion of group sameness. The fears of contamination, impurity, and loss of identity…are strong, and they reappear incessantly. (Cohen, Monster Theory, 15). The phenomenon of the mixed race is seen in Zemeckis's adaptation; this phenomenon was not a part of the original epic. This movie brings out the concepts of true origin and creates reasoning for monstrosity that originates literally from within us through desires of power and ethnic curiosity and sexuality. The movie, Beowulf, reveals the combination of the multiple levels of hybridity in order to establish a monster that comes from within our very selves. The first depiction of Grendel in Zemeckis's movie is that of a giant monster. He is enormous, but lacking the more appealing qualities of a human. His deformity lies in his lack of skin, hair, and the overgrowth and deformation of facial attributes. He is an “other”, but he can still be seen as having the physical “body” that is a man, even if it is overgrown. This physical hybridity between man and monster is clear. His actions resemble his physique. Ruthlessly killing and eating people, he stays true to his outer appearance which causes him to be regarded as a “demon.” Beyond the physical attributes, the linguistic differences that were present in Gardner’s adaptation are present in Zemeckis’s production as well. Through the point of view of the monster, it is clear that the language barrier is a factor in his frustration towards the people. Human language and noise is hurting his ear. The ear drum itself protrudes outside of the ear and causes him pain in hearing sounds, but specifically language. The mixing of languages and the pain it causes him parallels Grendel’s outward mixing of man and monster. His language is in a constant state of code-switching between an Old English and modern English dialect. When Grendel speaks with his mother the hybridity of languages is clear, he also catches Beowulf and Hrothgar off guard when he addresses them. It requires more attention and concentration to understand Grendel, though it is clear his hearing is hyper sensitive and in tune with the humans as well as his mother. Grendel’s portrayal in the movie coincides with his hybridity of races. The audience quickly learns the origins of Grendel. His features are the result of the mixing of a water demon and a human. Grendel the monster is half of the race of man. He goes through a physical change from his alive state to his death- a reversal and degeneration of form. Grendel appears as a giant underdeveloped human, but once he is nearing death he shrinks to the size of a man, and then finally his physical size matches his characteristics; he appears in his final position as a fetus- large head with an underdeveloped body. This degeneration links to his abortion by the society as a whole. Grendel’s half breed leave him a bastard to the society, unable to produce, communicate, or integrate. Grendel’s swift end leads the audience away from focusing on the hybrid creature that was lost, but the focus on the cause of the monstrous hybridity to begin with. Grendel’s mother is revealed to the audience within her lair. Beowulf once again must penetrate the lair in order to defeat the lineage of monsters. Though the motive is to stop the monster from attacking, much like it was in the original poem, our hero runs into the problem that what he is dealing with is a more human-like eroticized “other”. Cohen writes on women as monsters using aspects of postcolonial discourse: Women, like monsters, are a point of ambivalence…where “ambivalence” is that which (in Homi Bhabha’s formulation) conjoins colonialist attraction to repulsion;… As Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has observed, the subaltern woman tends to exist in the colonialist imaginary as a muted subject, as a body that produces only through an act of violation. (Cohen, Hybrids, 93). Up until this movie, Grendel’s mother was, in Spivak’s words “a muted subject”. Only she possesses the key to lineage through her powers as a woman. Without going too much into postcolonial feminism, it is still important to study the role of female monsters as they play a larger role in Zemeckis’s adaptation than they have before. In the epic poem, Grendel’s mother was a violent fighter, equivalent to any man, yet silent. In Gardner’s novel, the mother is disenfranchised from her son and society. Her language is completely absent and she holds no knowledge of it. In The Thirteenth Warrior, the Wendol queen fights Buliwyf, however, her language (if one could call it that) was more equated with wild screams. Women are equated with monsters, and in this sense, looking at a monster who transforms herself into an almost precise human is worthwhile. Spivak’s explanation of the postcolonial muted woman fits in that she becomes an object of both desire and disgust for our hero. Beowulf penetrates her lair in hopes to find another physically deformed creature, however, he is intrigued by her sexuality as well as what she offers him; political power. Grendel’s mother is equated with more power and language that does not come as a challenge as it was for her son, or the monsters in the other versions of the story. There is an important distinction between female and male monsters that should be made in that their female powers of maternity should not be denied or overlooked. In this case, the female moves from an absent character, to being a lead player in the cause of hybridity and monstrous creation. She is at the forefront of political and social upheaval. Through convincing the hero, Beowulf, to produce a son with her in exchange for a glorious and powerful kingship, she is bargaining Beowulf’s purebred lineage for political power. This exchange is highly costly in that desire for political power nearly sacrifices the survival of a kingdom. Grendel’s mother, however, cannot be left undefeated; her death becomes necessary to the destruction of the hybrid lineage that has been created. While in early texts, the need to kill the mother could have been seen as a destruction of just another monstrous attacker upon society, or a way to destroy an empire, we are now convinced through the movie that the reasoning behind her destruction is to prevent the lineage from continuing. Though one could look at the mother’s role from the point of view of the seducing female, it can also be seen more importantly, as a postcolonial fear of hybridity and the intermixing of races. If the female is gone, the fear of producing hybrid offspring has vanished. The idea of invasion and penetration into the female lair becomes a reverse penetration from the colonized/colonizer perspective and is moved to that of a trap to ensure the mixing and interbreeding can continue. Though it can be read as female maternity seeping through monstrous veins with a simultaneous urge to procreate and destroy (a mommy-monster syndrome), in the case of postcolonial hybridity, it can be read as a racial “other” attempting to infiltrate the society through mimicry, thus, reestablishing ideas of the evil and invasive “other” intruding into the civilized domain. The end result of this exchange of races and intermixing was first Grendel, then a dragon-man, both wreaking havoc and destruction within the society. Though both are half “other”, they still bear the marks of the dominant society, yet they are a burden upon society, living in the borderlands and unaccepted- both seen as a hybrid of shame and mistake that betrays the purity of a kingdom. The message of this new movie becomes clear, intermixing of races is what will produce the monstrous; we, through a failure to remain true to our origins produce the monstrous from greed for power and the deceit of our people. For today’s society, one that is seen as nearly done exploring and colonizing the world, the new fear of the “other” comes not from a need to overpower, but a need to sexually exploit or explore it. A different dominance arises from the colonizer’s standpoint; the land has been conquered, but what to do with the colonized is still in question. With the scope of the world becoming smaller as lands are nearly finished being inhabited and occupied, the fear that arises from the occupation is the need to populate and assimilate cultures through the process of reproduction. If one overlooks the consequences of commingling with a racial “other”, the result becomes dishonor in society. The true victim becomes the hybrid of the cultures; a racial, linguistic, and ethnic mix who no one desires to identify with or claim. Following the evolution of the tale, it is clear that the monster is altered and grossly exaggerated by society in order to represent a disapproval of accepting the “other” in any form. Beowulf’s enchantment towards the attractiveness and power of this indigenous woman results in a failure to understand dthe necessity of racial purity. While the hybrid produced is a dysfunctional and monstrous adversary of society, the message to take away is that he is not the only one suffering. Nor is it simply that the procreators of this hybrid are not the only ones who must deal with the consequences of parenting such a beast. As Waterhouse states, “the damage that a self-created monster wreaks [is not] confined to its creator, but…shows how individuals and society constantly interact” (Waterhouse, 29). In this aspect we see that hybridity in today’s age is one that humans are responsible for bringing onto the whole human race, not just on themselves. The hybridity is one that springs from within us, a physical representation of ourselves once we cross into the realm of the ethnic/cultural/racial “other” and this is what we should fear. As the legend of Beowulf is traced through its multiple interpretations starting from the original epic to the most recent remake into film, one can note that the desire to have an enemy be labeled as monstrous is a constant feature within each retelling. Our fascination with the “other” is not created through a complete contrast from ourselves. As the stories have shown, we desire hybridity as a means for enforcing the morals of domination and colonization. The “other” is labeled as a way to show difference from ideal society. As the story of Beowulf has evolved over the centuries, the meaning of hybridity has evolved along with it. Though physical difference is always seen as means of discrimination, the fetish of taking possession over other cultures and societies that do not compare to ours proves a more modern reason to make monster out of a people. The change in fear that has occurred over time comes more and more from within us rather than from an alien or subhuman life form. As the story of Beowulf is retold, each adaptation leaves the monster as less of an otherworldly creature and more of a product of ourselves. The fears of today’s age become that of commingling with those we attempt to colonize and overpower. The desires of humanity to conquer and dominate a people do not only stop at land and culture, they run deeper to a point where we are sexually assimilating and losing our identity to our colonized. This heavily stereotyped mixing of races results in a fear that the identities we worked centuries to create will be dissolved into an eerie creation of an unrecognizable and undistinguishable race. Thus, we portray all intermingling among people so separated culturally, linguistically, socially, and politically as monstrous in order to remind ourselves that hybridity, in all forms, will always be inherently evil. Works Cited Austin, Greta. "Marvelous Peoples or Marvelous Races." Marvels, Monsters, and Miracles. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publication, 2002. 27-55. Bartlett, Robert. "Medieval and Modern Concepts of Race and Ethnicity." Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 2001. University of St. Andrews. 30 Apr. 2008 <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/journal_of_medieval_and_early_modern_studies/v031/31.1 bartlett.html>. Beowulf. Dir. Robert Zemeckis. Perf. Ray Winstone, Anthony Hopkins, Angelina Jolie, Crispin Glover, Robin Wright Penn,John Malkovich, Brendan Gleeson, Alison Lohman. DVD. Paramount Pictures, 2007. Cohen, Jeffrey J. Hybridity, Identity, and Monstrosity in Medieval Britain on Difficult Middles. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. Cohen, Jeffrey J. "Hybrids, Monsters, Borderlands: the Bodies of Gerald of Wales." The Postcolonial Middle Ages. New York: St. Martin Cohen, Jeffrey J. "Monster Culture (Seven Theses)." Monster Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota P, 1996. 3-25. Gardner, John. Grendel. New York: Vintage Books, 1971. Heaney, Seamus, trans. Beowulf a Verse Translation. Ed. Daniel Donoghue. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002. The Thirtheeth Warrior. Dir. John McTiernan. Perf. Antonio Banderas, Vladimir Kulich, Dennis StorhøI, Clive Russell, Richard Bremmer. DVD. Touchstone Pictures, 1999. Waterhouse, Ruth. "Beowulf as Palimpsest." Monster Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota P, 1996. 26-40.