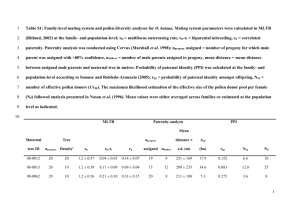

a new paternity law for the twenty-first century: of biology, social

advertisement