MLA Documentation

advertisement

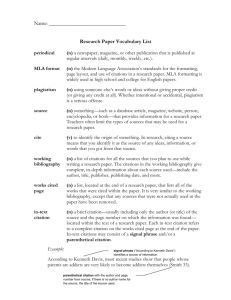

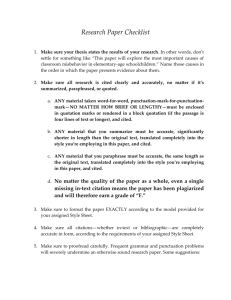

Mason Boyer English 100, 101 MLA Documentation– the Essentials This is a very brief guide to the essentials (what everyone should know, what every teacher expects) of MLA documentation. Documentation is endlessly detailed and complicated– the official MLA guide is over 300 hundred pages long! It is impossible and unimportant to memorize every single detail; I don’t have it all memorized, neither do your other teachers, nor should you. Rather, it is useful to be familiar with the basic principles, the names of the different parts, and what most instructors will expect of you, which is the purpose of this guide. For the more detailed information, do what all professionals do: have a resource handy that you can quickly and easily consult when necessary. For example, I have the OWL’s MLA format guide bookmarked on my browser, so any time I need to know how to do something that I do not have memorized, I look it up! MLA format can be broken down into three main parts: page layout, in-text citation, and the Works Cited page. Since we have discussed page layout elsewhere, this guide focuses on in-text citation and the Works Cited page. In-text citations and the Works Cited page are designed to work together to effectively achieve two important obligations without interfering with the readability of your writing: 1) you must tell your reader where you are getting your information from, and 2) you must give credit to the intellectual property of others. 1) where is your information coming from? Remember, research is for the writer, but sources are for the reader. The primary purpose of sources is to enhance the ethos (ethical appeal) of your writing. You want the reader to trust your information, to get the impression that your thoughts and opinions are derived from credible facts and examples, to see that what you are trying to say is the result of thorough consideration of multiple viewpoints. We borrow the credibility and authority of our sources in order to enhance our own credibility and authority as writers. 2) give credit where credit is due: Common knowledge does not need to be documented, but anything that you did not already know, that you would not have known without consulting the source, is someone else’s intellectual property and must be documented. Failure to do so is plagiarism. Such intellectual property even extends to word choice. In-Text Citations Simply, this refers to the parenthesis that need to be placed after every direct quote or at the end of any sentence that contains paraphrased source information. The basic in-text citation looks like this (Boyer 25). Its primary purpose is to tell the reader where to look on the Works Cited page in order to find the entire bibliographical entry. The only other thing that should ever appear in an MLA in-text citation is the page number that the quote or paraphrase appears on in the original source. Obviously, this can not be done for most online and other electronic sources, in which case the in-text citation will look more like this (Boyer). *The reason it is done this way is to avoid cluttering up the writing itself with long, messy, ugly, and distracting bibliographical references. Therefore, as a general principle, in-text citations should be as clean, short, simple, and clutter-free as possible. *In-text citations are considered a part of the sentence in which they appear; therefore, the period always, without exception, belongs after the citation, as you see in both examples above. Never place a period before an in-text citation. If a direct quote you use ends with a period, do not include the period in the quote; rather, end the quote, close quotation mark, then the citation, and then the period, like this: “blah blah blah” (Boyer 57). However, if a quote ends with a question or exclamation mark, then you must include it in the quote as it affects the meaning of the quote, and you still place a period after the citation, like this: “blah blah?” (Boyer 674). *If you are not sure what to put in an in-text citation, keep in mind that its primary objective is to tell the reader where to find the full entry on the Works Cited page; therefore, when in doubt, the first word of the full Works Cited entry should appear inside the in-text citation. Most Works Cited entries begin with the author’s last name, which is why the standard in-text citation looks like this (Boyer 31). In short: whatever a reader sees in an in-text citation, the reader expects to see a full bibliographical entry on the Works Cited page that begins with that word/words. For example, some sources do not have identified authors, and in many cases the bibliographical entries for such sources begin instead with the title, in which case the citation would look something like this (“Title” 54) or (“Title”). In the case of long titles, you may shorten the title in the in-text citation so long as it is easy to identify the source on the Works Cited page. The Works Cited Page The Works Cited page is where readers can find the complete bibliographical information for every source referenced in your essay. If there is no citation for a source in the actual essay, then it should not be listed on the Works Cited page. There are literally hundreds of types of sources, and variations of those types of sources, so it is impossible to memorize the rules for every entry. Sure, you may memorize several of the more common entries over time, but for the most part, you should keep a reference handy (I have the OWL bookmarked on my browser, for example) so you can look up the correct entry format on a case-by-case basis. Following are a few basic rules for the Works Cited page that are easy to memorize, that every teacher knows and expects to see: –The Works Cited page should begin on a separate page at the end of your essay, but it should have the same one-inch margins and header as the rest of your paper. Although the Works Cited page will have a header and page number, it does not count towards page length requirements. –center the title, Works Cited, on the first line of the first page (only the first page, if your Works Cited is longer than one page). Do not use quotation marks or underline the title. –the Works Cited page, like every other page in MLA format, should be evenly double-spaced. Do not skip extra lines or single space anywhere on the Works Cited page. –arrange entries alphabetically. Do not use numbers, bullets, dashes, etc. –the first line of each entry should be against the left 1" margin. If an entry is more than one line long, all subsequent lines should be indented ½" (one tab space, or five space bar spaces), sort of the opposite of a paragraph. For example: Thompson, Sarah and Peter Tournikov. “Mason Boyer: Bestest Teacher in the History of the Universe.” Wall Street Journal 15 December 2008: B2.