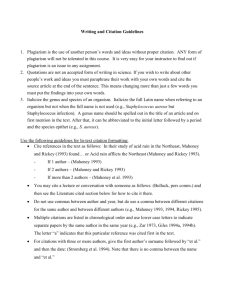

“A QUICK AND DIRTY GUIDE TO MLA DOCUMENTATION

advertisement

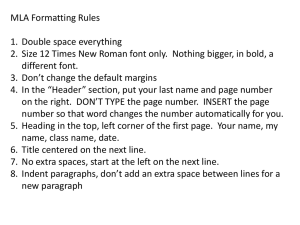

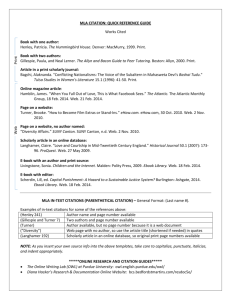

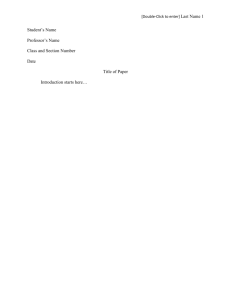

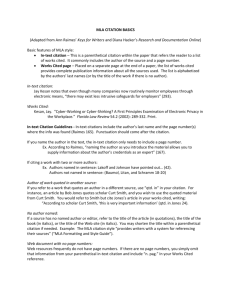

“A QUICK AND DIRTY GUIDE TO MLA DOCUMENTATION” BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE WRITING CENTER AT BURLINGTON COLLEGE (Stay tuned for “Everything You Wanted to Know About APA but Were Afraid to Ask”) Documentation is not fun or exciting. It is also not a “police action” designed to bust you for plagiarism. Instead… • It allows you to participate in a conversation about your topic. • It is an unavoidable part of writing a paper. • Everyone who incorporates research has to use documentation. • We’re a team, and we all wear the same jerseys. Luckily, you don’t have to memorize a thing! You can turn to many sources to see how to document your research. One of the best sources is the OWL: Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab. Google it! Their website shows you how to create “in-text citations” and a “Works Cited” page. Both of these are needed in every research paper. Why, you may ask? Because… • Your reader wants to know who you have invited into your paper! • In-text citations tell the reader when someone else besides you is “speaking.” Put the writer’s last name and the page number in parentheses, followed by a period. (Hirsh 25). This in-text citation is a flag. When the reader sees this, he or she knows that more information about your “guest” is on the Works Cited page at the end of the paper. The Works Cited page shows your sources in alphabetical order and gives publishing details. Interested readers can find the sources you used and learn more about your topic. The following info is required for a book with one author: Author. Title of Book. City of Publication: Publisher, Date of Publication. Mode of Publication. For example: Hirsch, Edward. Responsive Reading. Ann Arbor, Michigan: U of Michigan Press, 1999. Print. Writers must use both in-text citations and Works Cited entries. Having one without the other is like wearing only one shoe! The OWL gives examples of almost any kind of source you could find: books with editors, collections in an anthology, newspapers, films, scholarly journals, even YouTube videos and other electronic sources now commonly used in research. This is how you write an in-text citation for an online article called “How to Read a Poem” which does not give the author’s name and does not have a page number: (“How to Read a Poem”). The corresponding Works Cited entry looks like this: “How to Read a Poem.” Poetry Foundation. Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute. 2012. Web. 10 Jan 2013. This citation includes all the information available about the source, and it gives the mode of publication and the date accessed. Now there is a quiz! Let’s say you quote an online article that does have an author but no page numbers. What goes in the parentheses for your in-text citation – the author’s name or the title of the article? “Emerson was an avid, creative, and intoxicated reader, and he was an assiduous journal keeper” (???) Here’s the correct in-text citation: “Emerson was an avid, creative, and intoxicated reader, and he was an assiduous journal keeper” (Hirsch). Here’s the correct Works Cited entry: Hirsch, Edward. “Ralph Waldo Emerson: Life is an Ecstasy.” Poets on Poetry. The Academy of American Poets. 1997. Web. 10 Jan 2013. REMEMBER: You don’t have to remember this! Just consult the OWL or your MLA handbook every time you write a research paper – you can’t get it wrong! Visit the Burlington College Writing Center if you need help!