MS Word Format-print friendly 635 KB

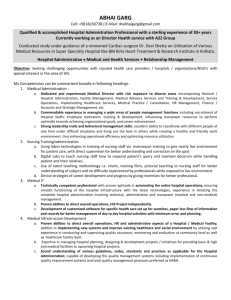

advertisement