Interactive Shoulder Part 1

Bones Structure

By Primal Pictures

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is a small sample of the Interactive

Shoulder CD in the ground breaking Primal Pictures 3-D Anatomy CD ROM

series

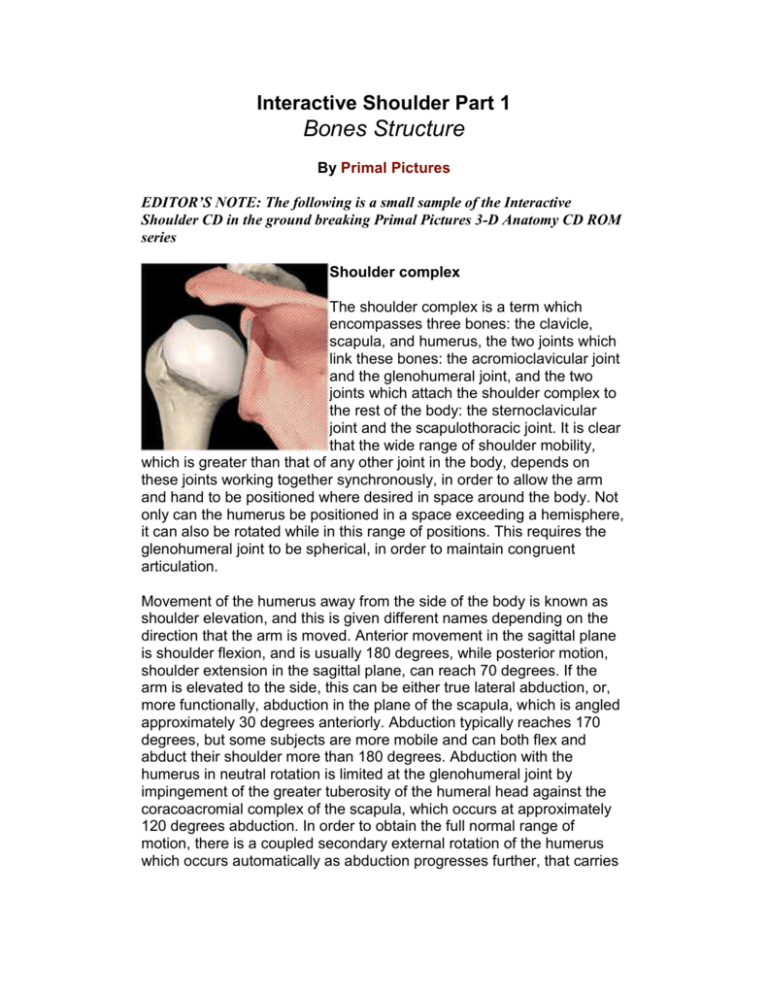

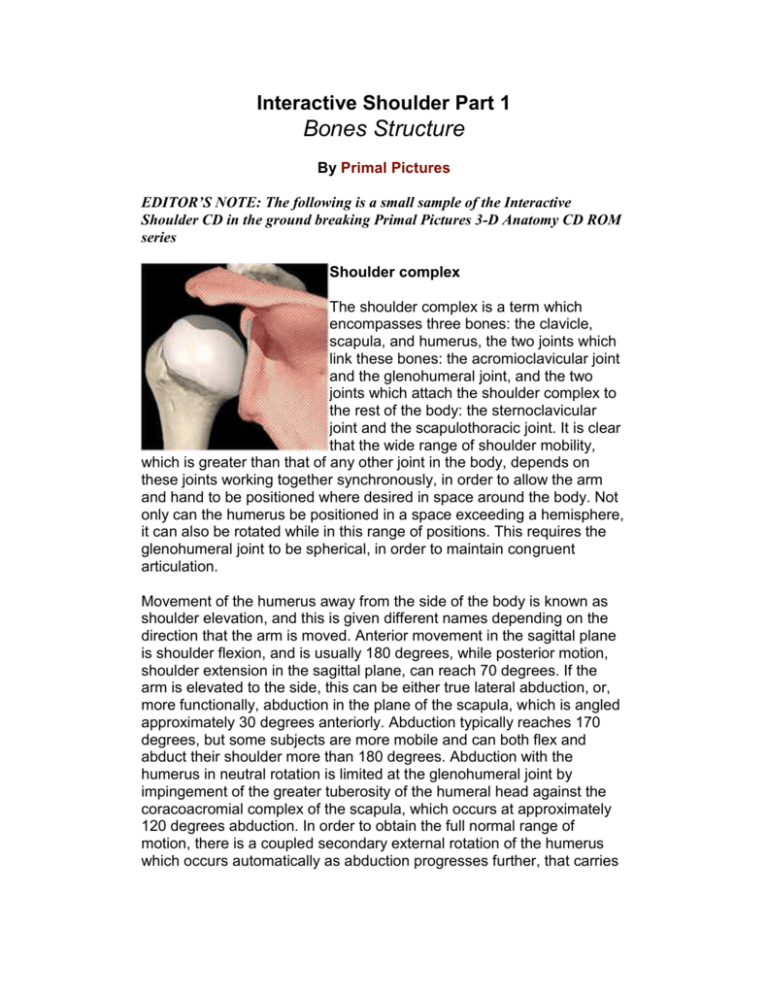

Shoulder complex

The shoulder complex is a term which

encompasses three bones: the clavicle,

scapula, and humerus, the two joints which

link these bones: the acromioclavicular joint

and the glenohumeral joint, and the two

joints which attach the shoulder complex to

the rest of the body: the sternoclavicular

joint and the scapulothoracic joint. It is clear

that the wide range of shoulder mobility,

which is greater than that of any other joint in the body, depends on

these joints working together synchronously, in order to allow the arm

and hand to be positioned where desired in space around the body. Not

only can the humerus be positioned in a space exceeding a hemisphere,

it can also be rotated while in this range of positions. This requires the

glenohumeral joint to be spherical, in order to maintain congruent

articulation.

Movement of the humerus away from the side of the body is known as

shoulder elevation, and this is given different names depending on the

direction that the arm is moved. Anterior movement in the sagittal plane

is shoulder flexion, and is usually 180 degrees, while posterior motion,

shoulder extension in the sagittal plane, can reach 70 degrees. If the

arm is elevated to the side, this can be either true lateral abduction, or,

more functionally, abduction in the plane of the scapula, which is angled

approximately 30 degrees anteriorly. Abduction typically reaches 170

degrees, but some subjects are more mobile and can both flex and

abduct their shoulder more than 180 degrees. Abduction with the

humerus in neutral rotation is limited at the glenohumeral joint by

impingement of the greater tuberosity of the humeral head against the

coracoacromial complex of the scapula, which occurs at approximately

120 degrees abduction. In order to obtain the full normal range of

motion, there is a coupled secondary external rotation of the humerus

which occurs automatically as abduction progresses further, that carries

the greater tuberosity posteriorly to avoid impingement. Ranges of

motion tend to decrease with advancing age.

If the shoulder is slightly flexed, so that the humerus is brought anterior

to the thorax, the shoulder can be adducted, bringing the arm towards

the centerline of the body, by approximately 60 degrees. The arm can

also be moved in a horizontal plane after abducting the shoulder 90

degrees, and this allows the arm to move across the front of the body to

approximately 140 degrees range of motion, and 45 degrees posteriorly

from the lateral direction. Thus, the shoulder complex allows an overall

range of motion of 180 degrees in almost all directions. This range of

motion of the humerus in space is accomplished by motion of the

scapula relative to the thorax, in addition to the dominant glenohumeral

motion. This sharing of mobility has been studied most extensively for

humeral abduction in the plane of the scapula. Different researchers

have found variations in motion, but overall it seems that 60% of this

motion arises at the glenohumeral joint and 40% at the scapulothoracic

joint. Similarly, shoulder motion with the humerus in a horizontal plane

includes scapular protraction and retraction movement. This scapular

mobility is essential for maintaining some reduced shoulder function if

arthritis with loss of bone requires an arthrodesis of the glenohumeral

joint. Scapular motion is linked to the clavicle, which controls the position

of the acromioclavicular joint in relation to the thorax at the

sternoclavicular joint.

Rotation of the humerus can also compound the mobility of the shoulder

complex. When the arm is alongside the thorax with the elbow flexed 90

degrees, internal rotation is limited by the hand reaching the body, while

external rotation is limited to 90 degrees by tightening of the soft tissues

crossing the anterior aspect of the shoulder, such as the anterior

glenohumeral ligaments and subscapularis muscle. Similar ranges of

humeral rotation are found when the humerus is rotated with the

shoulder abducted 90 degrees. If the elbow is extended when rotation

occurs, the hand rotates further than the humerus, due to the additional

mobility of the radioulnar joints in the forearm.

The great mobility of the shoulder complex allows the hand to be

positioned in space; it also allows the hand to reach to a particular point

via different paths of motion. This adaptability has led to some

apparently paradoxical observations on complex shoulder motion, most

notably that known as Codmans paradox. This paradox poses the

question of whether the humerus is in a position of internal or external

rotation when the forearm is held horizontally above the head. If the

humerus is returned to the side of the body by flexion of the

glenohumeral joint in the sagittal plane, the forearm ends up across the

front of the body, so the humerus is in internal rotation . Conversely, if

the humerus is lowered by rotating in an arc of adduction in the coronal

plane, the forearm ends up pointing away from the body the humerus

clearly in external rotation. This paradox arises because the path taken

through space, and the final destination, are affected by the sequence in

which rotations occur about perpendicular axes. This phenomenon is

well known among engineers, who refer to the three mutually

perpendicular rotations as pitch, yaw and roll, and conventions are used

to ensure uniformity of the sequence of application of the rotations and,

therefore, of the motion described.

Scapula

This bone acts primarily to provide extensive attachment areas for

muscles that contribute to the rotator cuff: supraspinatus, infraspinatus

and subscapularis. They focus their tensions across the glenohumeral

joint, pulling the head of the humerus medially, thus causing the

compressive joint force component that stabilizes the head of the

humerus into the relatively shallow articulation of the glenoid. The blade

of the scapula can be transparently thin, and it is protected from buckling

failure, under the actions of the muscles which attach across it, by the

spine of the scapula, that separates the attachments of the

supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. The scapula depends on the

clavicle to control its position, as the link to the thorax is somewhat

tenuous. The scapula is effectively suspended below the lateral end of

the clavicle by the coracoclavicular ligaments, and is also joined to it at

the acromioclavicular joint, which is surrounded by acromioclavicular

ligaments.

Glenohumeral joint

This joint has the largest range of motion in the body. It is essentially

part-spherical. In order to allow the wide range of motion, the concavity

of the glenoid has a shallow rim, to delay impingement by the humerus

as it approaches the limits of motion, that is augmented by a soft labrum.

The shallow articulation means that the joint has little inherent stability,

and so it depends on the coordinated actions of the muscles to maintain

stability, particularly those which constitute the rotator cuff. The

ligaments of the glenohumeral joint capsule only act to stabilize the joint

when tightened, which only occurs at the limits of the ranges of motion.

The lack of restraint in the glenohumeral joint means that although it has

a spherical geometry, there is usually some inherent laxity. The concave

surface of the glenoid often has a greater radius of curvature (i.e. it is

relatively flat) than does the articular surface of the head of the humerus.

This leads to a relatively small area of contact between them. This has

two side effects: firstly, it causes the joint contact pressure to rise;

secondly, it allows some joint mobility. This is seen as a linear translation

movement, that is a slight subluxation, of the humeral head relative to

the glenoid as the head rotates. If the head were located in a glenoid

with matching radius of curvature, then it would not be free to translate,

and so it would be forced to spin in one place as the humerus rotates,

and this causes a relative sliding motion between the articular surfaces.

This is the case for the hip joint. The glenohumeral joint has some rolling

motion mixed in with the sliding: as the humerus starts a movement of

external rotation , for example, the humeral head will initially roll

posteriorly over the surface of the glenoid, perhaps for 3 mm. As it

encounters increasing restraint from the slope of the labrum, so it tends

to stop rolling and start sliding in one place . Noting this arrangement for

natural joints, some joint replacements have been made with their metal

humeral head with a smaller radius than the polyethylene glenoid

surface, in order to allow these small natural secondary movements. The

downside to this, however, is the possibility of increased wear due to the

raised contact pressure. The glenoid is somewhat egg shaped, with the

narrower part superiorly, and it is typically 35 mm in superior-inferior and

25 mm in anterior-posterior directions. Sometimes, the face of the

glenoid is angled away from the normal orientation, and this can be

exaggerated by arthritic erosions, and leads to a tendency to instability,

as the head of the humerus tends to slip off.

The articular surface of the humeral head is nearly hemispherical and is

angled superiorly approximately 45 degrees and posteriorly

approximately 30 degrees. This allows greater ranges of abduction and

external rotation before impingement occurs. When transverse sections

of the proximal humerus are viewed, the articular surface is seen not to

be centered on the long axis of the shaft: it is offset posteriorly. The

combination of offset and angulation is variable, and this is allowed for

by some shoulder prosthesis designs.

There is little data available about forces acting across the glenohumeral

joint, but a relatively simple analysis can show that it will reach three

times body weight, and perhaps higher, during abduction to 90 degrees

while supporting a load of 12% body weight in the hand. The force

analysis shown in the diagram has been simplified greatly by assuming

that all of the shoulder elevation moment comes from the deltoid tension.

In reality, this moment is shared with other muscles which act to elevate

the humerus and also to stabilize the head of the humerus into the

glenoid, especially the supraspinatus. It is possible to apportion muscle

forces using schemes which allow for the number of muscle fibers (the

physiological cross-sectional area) and the degree of muscle activation,

that can be assessed by electromyography. However, all other muscles

have a humeral elevation moment arm which is smaller than that of the

deltoid, and this means that the simplification leads to a lower bound for

the muscle force acting across the glenohumeral joint. The force vector

diagram shows the relative magnitudes of the muscle and joint forces,

and also their directions in the plane of the scapula. It is clear that the

majority of the joint force is caused by the muscle action. The resultant

joint force shown will cause the head of the humerus to press against the

central superior rim of the glenoid. Activities such as shoulder flexion or

abduction while holding a weight of 2kg in the hand lead to joint forces of

approximately 1.5 body weight. These forces act centrally and superiorly

or superiorly and anteriorly onto the glenoid, giving a tendency for the

head of the humerus to sublux superiorly. When this occurs, the

subluxation is limited by the head of the humerus impinging against the

coracoacromial ligament, which passes in an anterior-posterior direction

above the head of the humerus.

Scapulothoracic joint

The scapulothoracic joint is not a true articular joint, but simply a plane of

separation of the scapula and the subscapularis muscle from the thorax,

that allows relative motion. The thoracic surface here is the superficial

aspect of the serratus anterior overlying the ribs. It allows the scapula to

slide anteriorly/posteriorly around the rib cage with shoulder

protraction/retraction. As it does so, the scapula rotates about a vertical

axis, since the ribs are curved, and so shoulder protraction causes the

glenoid to face more anteriorly, and more posteriorly with retraction. The

scapula also rotates in its own plane as the humerus is

abducted/adducted . In shoulder abduction, approximately 40% of the

humeral abduction motion occurs at the scapulothoracic articulation.

There is typically some 75 degrees motion here in 180 degrees

abduction. By rotating the scapula, the glenoid is angled superiorly as

the humerus is abducted, and so superior impingement is delayed.

Further, the superior angulation of the glenoid allows the compressive

joint force to remain within the articular concavity, which is stable. If the

scapula did not abduct with the humerus, then the muscles would pull

the head of the humerus into inferior (caudal) subluxation. Rotation of

the scapula in its own plane is caused by coordinated actions of the

serratus anterior and the upper and lower parts of the trapezius muscles:

their actions can create a rotation moment acting onto the scapula

without a resultant force tending to move it linearly. Scapular protraction

and retraction are due to actions of serratus anterior, and rhomboid plus

trapezius actions, respectively.

Movement at the scapulothoracic joint is essential to patients who have

their glenohumeral joint arthrodesed, as some upper limb mobility still

remains.

Acromioclavicular joint

This joint is loaded primarily in compression by the actions of the

muscles which pull the shoulder towards the centerline of the body, such

as the anterior pectoral muscles. There is also a superior-inferior

shearing load, due to muscles which tend to elevate the clavicle, but this

is counteracted by the inferior component of the tensions in pectoralis

major and anterior deltoid, which pass to the humerus from the clavicle.

Since the acromioclavicular joint surfaces are oblique, the loads applied

tend to cause the lateral end of the clavicle to sublux superiorly if the

joint is disrupted: the lateral end of the clavicle tends to slide uphill

across the slope of the joint surface on the acromion. This tendency is

resisted by the coracoclavicular ligaments, damage to which allows the

characteristic superior prominence of the end of the clavicle. The

acromioclavicular ligaments which surround the lateral end of the

clavicle are slack enough to allow motion between the clavicle and the

scapula, with a relative scapular rotation of approximately 20 degrees

during humeral abduction, and shearing actions at the joint during

shoulder protration/retraction, when the motion is centered at the conoid

part of the coracoclavicular ligaments. Similarly, shoulder abductionadduction motion causes the scapula to rotate about a horizontal

anterior-posterior axis relative to the clavicle (which is itself rotating

similarly about the sternoclavicular joint), that is centered amidst the

coracoclavicular ligaments. Since these attach away from the end of the

clavicle, this motion also causes the end of the clavicle to slide across

the surface of the acromion as the scapula rotates.

Clinical Pathology Text

The suprascapular nerve is located in the supraspinous or spinoglenoid

notch, at the superior border of the supraspinous fossa. In this location

the suprascapular nerve may be compressed by a ganglion or

entrapped, secondary to thickening of the suprascapular ligament.

The origin of the coracoid is superior and medial to the glenoid on the

scapular neck, and the tip of the coracoid projects anterior and lateral to

the glenoid. The coracoid is an important surgical landmark because

neurovascular structures travel along its inferomedial surface.

The acromion is classified as one of three types, depending on its

morphology. A type 1 acromion has a flat or straight undersurface with a

high angle of inclination. A type 2 acromion has a curved arc and

decreased angle of inclination. A type 3 acromion is hooked anteriorly,

with a decreased angle of inclination. The angle of inclination is formed

by the intersection of a line drawn from the posteroinferior aspect of the

acromion to the anterior margin of the acromion with a line formed by the

posteroinferior aspect of the acromion and the inferior tip of the coracoid

process.

At the lateral angle of the scapula is the glenoid cavity (glenoid fossa)

with its supra- and infraglenoid tuberosities. The glenoid version angle

varies, and may contribute to instability patterns of the shoulder.

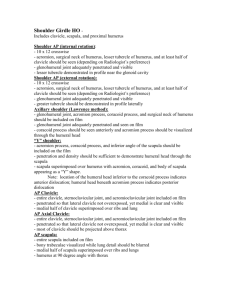

Acromioclavicular Separations

There are three types of AC separations: type 1is a sprain or incomplete

tear of the AC joint capsule, type 2 is a complete tear of the AC joint

capsule with intact coracoclavicular ligaments, and type 3 involves

disruption of both the AC joint capsule and the coracoclavicular

ligaments. Widening of the AC joint space to 1.0 to 1.5 cm and a 25% to

50% increase in coracoclavicular distance is associated with tearing of

the AC joint capsule and sprain of the coracoclavicular ligament.

Widening of the AC joint to 1.5 cm or a 50% increase in the

coracoclavicular distance correlates with coracoclavicular ligament

disruption.

Arthritis

Degenerative osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint is relatively

common. It is characterized by cartilage-space narrowing, hypertrophic

bone formation, subchondral cysts, and associated soft-tissue

abnormalities of the rotator cuff. In rheumatoid disease, unlike

osteoarthritis, joint space narrowing is more uniform and symmetric,

without osteophytosis. Rheumatoid erosions occur at the margins of the

articular cartilage, including the greater tuberosity.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the humeral head ( Slide 1 , Slide 2 ) can

usually be differentiated from osteoarthritis on MR scans by the

restriction of subchondral low signal intensity ischemia to the humerus,

without associated glenoid involvement (i.e., sclerosis). Avascular

necrosis of the humeral head is associated with trauma, steroid use,

sickle-cell disease, and alcoholism

CLICK HERE for more information on the Primal Pictures 3-D Anatomy

series and for details on exclusive PTontheNET.com member discounts

Disclaimer

No warranty is given as to the accuracy of the information on any of the pages in this website. No responsibility is accepted for

any loss or damage suffered as a result of the use of that information or reliance on it. It is a matter for users to satisfy themselves

as to their or their client’s medical and physical condition to adopt the information or recommendations made. Notwithstanding a

users medical or physical condition, no responsibility or liability is accepted for any loss or damage suffered by any person as a

result of adopting the information or recommendations.

© Copyright Personal Training on the Net 1998 2003 All rights reserved