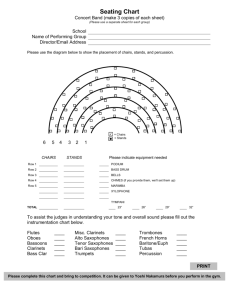

Whitwell on Seating Plan Theory - Whitwell

advertisement

Whitwell on Seating Plan Theory Many years ago I was rehearsing the Ernst Toch, Spiel for 44 winds with some very fine players. There was no problem playing the composition, but for some reason it did not sound good. One day, on the spur of the moment, I changed the seating plan and suddenly -- to my very great surprise -- the performance sounded great, with no further rehearsal. This was the moment I fully realized that there are acoustic principles at work which greatly affect performance. I then spent some years in experimentation and in addition was on a scientific committee hosted by the instrument maker, Conn, which studied the individual characteristics of wind instrument tone as the tone travels from stage to audience, etc. What follows are some principles I arrived at, and which I believe in completely. I offer them for contemplation and suggest one might want to experiment with these principles. One can pass out a drawing to the band and they can easily find their new positions. Play something familiar in your normal seating position. Then have the players quickly move to the new position and play the same thing again so you can listen [from the front] to the difference. You may not like the change, of course. But what you will hear with my plan is a more organ-like sound, a clear focused bottom of the sound and clearer, cleaner internal voices. First Basic Principle Wind instruments in ensemble sound better if there is more space between players than you would find in an orchestra. This is because string instruments, all being wood boxes, cross-resonate. Strings sound good even if they sit closely together. Winds do not. Wind instruments require a certain "envelope of space" for the individual tone to develop on stage before it travels out to the audience. If they are sitting close together, the clothes of the nearby players absorb critical overtones before they have a chance to travel off stage to the audience. Try using your present seating plan but have the players move more closely together. Perform some hymn-like music. Have them quickly move, keeping the same plan but moving apart until there is nearly one chair distance between players. Play the same passage again. You will be astonished. 1 Second Basic Principle I am sure every conductor has heard of the pyramid principle. This has been discussed by conductors for centuries, as for example by Michael Praetorius in book III of his Syntagma Musicum of 1619. The problem is that the ear tends to hear upper partials more than lower partials. Today we know the reason. The human brain actually "turns up the volume" for sounds in the octave above third space C, treble clef. The brain has learned to do this over thousands of years in order to help the hearing of language (probably beginning with hearing the tiger outside the cave). As a result, the listener in a concert actually hears something the ensemble did not perform. In order to counteract this, the conductor must artificially balance the ensemble = more bottom, less top. The conductor's goal is to create an illusion under which the listener thinks he heard what the composer wrote. This is critical with a wind band, for if the conductor does not do this, two things happen: [1] the band sound is top heavy and strident, not organ like (organ-like meaning like the overtone series) and [2] the audience does not enjoy being bombarded by high partials for two hours. It is unpleasant. I employ this principle in other ways. When you have a melody which is doubled in octaves, no matter how many players on either line, my rule is to make the bottom octave 2/3 of the sound and the top octave 1/3 of the sound. If you do this, the listener hears them as 50 - 50%. If they actually play 50 - 50%, the listener thinks he hears 2/3 top and 1/3 bottom. I also use this principle for the endings of long tones, as in a composition that ends in a whole-note. Instead of giving a gesture that makes everyone stop immediately together, I give a long gesture with the arm and tell the players to stop according to the tessatura. That is, the flutes and first clarinet stop as soon as the arm begins to move, horns and sax half way along, and the last person to stop is the tuba (with a little "tail" to the sound). What the listener hears is a beautiful, resonant cut-off and the listener hears the full chord. If everyone stops together, what the listener hears is a chord with no bottom (the ear tries to hang on to the upper partials). You 2 will hear this especially in the short note at the end of a march. Michael Praetorius goes so far as to recommend that it sounds great if the bass continues for 4 beats after everyone else stops! But, of course, he was thinking of the sound in a great cathedral. There, it would be a great effect. Another problem: Because the brain hangs on to the upper partials the listener will also hear a little acoustic “tag” that appears to go up (say "mamma" with the last syllable being a higher pitch). This is something created by the brain and is not actually there. That is, you will hear it but you will not see it on an oscilloscope. But it is an important principle. My rule with a wind band on any kind of last note the band plays together: Let us never end together. Ironic! Third Basic Principle Wind bands sound better if the seating plan is deeper, and not wider. Many bands use only four rows. I use 6 rows, even with an ensemble of 50 players. This only means the percussion must go on one or both sides and not in back. They look good in back, but placing them there prevents the band from having a seating plan that sounds good. Also very important is that by having a seating plan that has depth, rather than width, it makes possible more space between the individual players. Fourth Basic Principle If the tubas (and euphonium) are centered in the last row, with the trombones centered in front of them, then a combination effect takes place which makes the bass notes of chords centered, more beautiful and more clear. This never happens if the tubas are on the same row as trombones. Then one only hears the individual instruments, never a unity of the sound. The same principal applies to the tenor and baritone range instruments: bassoons, tenor and baritone sax, bass clarinets. They can go anywhere, but they must be in a 3 block together if they serve to clarify the tenor-baritone sound of the chordal structure. Fifth Basic Principle Rows of flutes and clarinets must not face each other. Angle the rows so that the rows point slightly toward the audience, as if aiming just behind the conductor, and not at each other. If they face each other, their upper partials clash above the band, before traveling to the audience, giving a brittle sound to the entire band. My personal seating plan recognizes the above principles and at the same time is a personification of the overtone series). The central core is in straight rows. These are, counting from the back row, moving toward the conductor: last row: tubas and euphoniums next row: trombones next row: horns next row: saxes next row: bassoons, low clarinets, etc front row: oboes podium I put clarinets on my left, flutes on my right. Each in straight rows branching away from the central core, above. These rows are angled not towards each other, but as if they were pointing at a point behind the conductor. I put trumpets on my right, behind the flutes. This is so they can blow across the ensemble. The trumpets are the most directional of all wind instruments. By filtering their sounds through the players’ bodies (rather than pointing at the audience) it allows them to fill the instruments and play with a full sound -- not hold back because they see audience members going cross-eyed. 4 Because of this plan, based on depth instead of width, there is plenty of room for the percussion on the left and right sides (behind clarinets and trumpets). In fact, this brings them closer to the ensemble (for hearing purposes) and closer to the audience (for eye purposes). 5