RADICAL CHRISTIANITY IN THE HOLY LAND: A COMPARATIVE

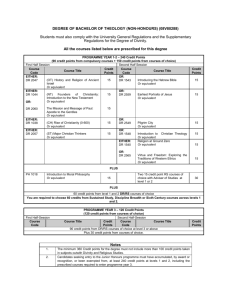

advertisement

RADICAL CHRISTIANITY IN THE HOLY LAND: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF LIBERATION AND CONTEXTUAL THEOLOGY IN PALESTINE-ISRAEL By Samuel Jacob Kuruvilla Theology Department University of Exeter Exeter UK April 2009 RADICAL CHRISTIANITY IN THE HOLY LAND: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF LIBERATION AND CONTEXTUAL THEOLOGY IN PALESTINE-ISRAEL Submitted by Samuel Jacob Kuruvilla, to the University of Exeter as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology, April 2009. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signature) ......................................................................................... ii Thesis Abstract Palestine is known as the birthplace of Christianity. However the Christian population of this land is relatively insignificant today, despite the continuing institutional legacy that the 19th century Western missionary focus on the region created. Palestinian Christians are often forced to employ politically astute as well as theologically radical means in their efforts to appear relevant within an increasingly Islamist-oriented society. My thesis focuses on two ecumenical Christian organisations within Palestine, the Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Centre in Jerusalem (headed by the Anglican cleric Naim Stifan Ateek) and Dar Annadwa Addawliyya (the International Centre of Bethlehem-ICB, directed by the Lutheran theologian Mitri Raheb). Based on my field work (consisting of an in-depth familiarisation with the two organisations in Palestine and interviews with their directors, office-staff and supporters worldwide, as well as data analyses based on an extensive literature review), I argue that the grassroots-oriented educational, humanitarian, cultural and contextual theological approach favoured by the ICB in Bethlehem is more relevant to the Palestinian situation, than the more sectarian and Western-oriented approach of the Sabeel Centre. These two groups are analysed primarily according to their theological-political approaches. One, (Sabeel), has sought to develop a critical Christian response to the Palestine-Israel conflict using the politicotheological tool of liberation theology, albeit with a strongly ecumenical Westernoriented focus, while the other (ICB), insists that its theological orientation draws primarily from the Levantine Christian (and in their particular case, the Palestinian Lutheran) context in which Christians in Israel-Palestine are placed. Raheb of the ICB has tried to develop a contextual theology that seeks to root the political and cultural development of the Palestinian people within their own Eastern Christian context and in light of their peculiarly restricted life under an Israeli occupation regime of over 40 years. In the process, I argue that the ICB has sought to be much more situationally relevant to the needs of the Palestinian people in the West Bank, given the employment, sociocultural and humanitarian-health opportunities opened up by the practical-institution building efforts of this organisation in Bethlehem. iii Acknowledgements I would like to state that all credit for the successful completion of this doctoral dissertation goes to God alone. The Divine Presence helped me to finish this work, and it must always remain a tribute to the kindness, glory and honour of God Almighty. In addition, this Ph. D would never have been completed without the selfless help and financial support of my family, both in India and Oman, as well as in this country. My heartfelt thanks goes to my dear father, dearest mother, beloved sisters, brother-in-law and my one and only wife for all the sacrifices they have made to make this work possible. Indeed, this Doctor of Philosophy in Theology will always be a lifelong tribute to the love, care and concern of my family for my personal welfare in the midst of the most trying of circumstances, both in this country as well as in my native land of Kerala (in South India). On the academic side, I must always remain exceedingly grateful to my supervisors, both present as well as past, for their perseverance in guiding me into hoping for a positive outcome to my work. I would like to express my gratitude to my first supervisor in the Politics department in Exeter, Dr. Larbi Sadiki for his agreeing to guide me as a newcomer to the United Kingdom from New Delhi, India. Much of the initial spadework for this thesis was done under the supervision of Professor Michael Dumper, again of the Politics department, to whom I must always be grateful. Professor Nur Masalha, Director of the Centre for Religion and History and Holy Land Research Project, School of Theology, Philosophy and History-St Mary's University College (University of Surrey), also played an important role in guiding and encouraging me during the crucial fieldwork periods in Israel-Palestine as well as during my transition from a purely politics-driven approach to that of a historical, theological and politically-oriented approach within the University of Exeter. I remain grateful to him for all his help and support as well as the crucial links he provided to suitable resource persons and academics within the IsraelPalestine and UK spectrum. I also remain very grateful to him for his continuing encouragement of my academic-publishing development through the medium of the Holy Land Studies Journal of which he remains the editor. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Daphne Tsimhoni of the Department of Humanities and Arts Technion at the Israel Institute of Technology (IIT)-Haifa for her hospitality and patience in granting me an interview at her residence in Zikhron Ya’aqov, Israel in 2007. Finally, all credit is due to my present supervisor, Professor Timothy J. Gorringe of the Theology department in iv Exeter, for his kind help and sound academic critique that guided me through the somewhat perilous shoals of liberation/contextual theological debate, initially about which I had little awareness. Thanks to him alone that I have been able to finish this work in a creditable fashion. I would, in particular, like to thank him for his encouragement of my own critical faculties and ability to think independently, qualities that had somewhat rusted during my years in the wilderness, both in this country as well as in my native India. The staff at Exeter University libraries helped me considerably during the course of this work, and special mention must be made of the help rendered by Paul Auchterlonie of the Arabic (Middle Eastern Studies) collection in the Old Library. Extensive reference work was conducted at the Orchard Learning Resources Centre at the Selly Oaks Campus of Birmingham University and many thanks are due to the very helpful staff at this institution. Mention cannot but be made here of the hospitality and generosity shown me by the directors, staff and associates of my two main research topical centres in IsraelPalestine: The Sabeel Centre for Ecumenical Liberation Theology in East Jerusalem and Dar Annadwa Addawliyya (The International Centre of Bethlehem) in BethlehemPalestine. I remain very grateful to both my internal examiner Professor Esther Reed as well as my external examiner Professor Mary Grey for their agreeing to examine this Ph.D thesis jointly and for their faith in my abilities as a researcher, which was justified in their passing me for the recommendation of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology. Many people, who for reasons of space will remain unnamed, helped me to survive in Exeter until I got married to Saira, who then went on to become the love of my life and my boon companion. Her coming into my life helped me in my weakest moments and ultimately contributed in a remarkable measure towards my finishing this Ph. D. Finally, I cannot end this short acknowledgement without mentioning the financial, moral, emotional and spiritual help that fellow Christian believers gave me during the course of my doctoral research work in Exeter. Special mention must be made of Simon, Mary, Eugene, Emily, Kel, Nerys, Nandu, Reena, Yesudas, Brother Justus and Sister Lyla of Bethel Church as well as Pastor Ayo and Sister Margaret of MFM Ministries International in Exeter for their immensurable spiritual, moral and financial support to me. The last two individuals and their respective spouses contributed a lot towards the spiritual and material well-being of our family for which my wife and I are exceedingly grateful. To God alone, through Jesus Christ, is the glory, for ever and ever. Amen. v 21 Be not afraid, O land; be glad and rejoice. Surely the LORD has done great things. 22 Be not afraid, O wild animals, for the open pastures are becoming green. The trees are bearing their fruit; the fig tree and the vine yield their riches. Joel 2:21-22 ‘The Bible shows how the world progresses. It begins with a garden, but ends with a Holy City.’ -- Phillips Brooks. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Thesis Abstract Acknowledget iii iv CHAPTER 1-Introduction...................................................................................................1 1.1 Aims of this Thesis…………………………………………………………………. ...1 1.2 Research Questions and Methodology………………………………………………...2 1.3 Historical Introduction……………………………………………………………… ...4 1.3.1 Introduction: The religious importance of Jerusalem…………………………. ..4 1.3.2 Muslim and Turkish rule in Palestine: Impact on the Christians of the Holy Land…………………………………………………………………………………...8 1.3.3 The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem………………………………..11 1.3.3.1 Greek-Palestinian clergy-laity issues………......................................... .14 1.3.4 The British Mandate Period…………………………………………………… 16 1.3.5 The Jordanian Period…………………………………………………………. .22 1.3.5.1 The Church and the Israeli State……………………………………… .23 1.3.5.2 The Church and the Palestinian National Struggle…………………… .24 1.3.5.3 The Christian interest in Jerusalem…………………………………… .26 1.3.6 Palestinian Protestant Church History since 1948: The Anglicans and Lutheran Protestants of Jerusalem…………………………………………………………….. .27 1.4. Land and the Question of the ‘Holy’ Land………………………………………… .34 1.4.1 The land of Palestine………………………………………………………… .34 1.4.2 The Land and Justice………………………………………………………… .35 1.4.3 Impact of the 1967 war on Palestinian Christians: Christian demographic decline……………………………………………………………………………… .37 1.4.4 Post-1967 Changes in the Land of Palestine: The Impact of Islamism.............38 1.5 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….. .44 CHAPTER 2 - Political and liberation Theologies: Implications for Palestine-Israel (The Intellectual Context of Ateek and Raheb’s work)..............................................................46 2.1 Political and Liberation Theologies in Latin America and Asia……………………..47 2.1.1 The Rise of Liberation Theology……………………………………………… 47 2.1.2 The main emphases of liberation theology…………………………………… .49 2.1.3 Liberation theology in Palestine………………………………………………. 53 2.2 Contextual Theology: A Definition………………………………………………… .54 2.3 Early influences in contextualisation of theology in Palestine……………………… 57 2.3.1 Fountainhead of contextualisation: The Al-Liqa Centre in Bethlehem………. .57 2.3.2 Patriarch Michel Sabbah……………………………………………………… .63 2.3.4 Bishop Riah Abu El-Assal (former Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem)…………. .67 2.4 The concerns of Palestinian theology………………………………………………. .69 2.5 Western theological thought and the question of Palestine………………………….69 2.5.1 Jewish Theology of Liberation: Rabbi Marc Ellis……………………………. .70 2.5.2 Rosemary Radford Ruether and the theology of Christian anti-Semitism in the West………………………………………………………………………………… .72 2.6 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….. .77 vii CHAPTER 3 - The ‘Sabeel’ Ecumenical Liberation Theology Centre in Jerusalem: A study of the theology, praxis and politics of Naim Stifan Ateek.......................................79 3.1 The Origins and Praxis of Sabeel…………………………………………………….80 3.2 Use of the Exodus narrative in Palestinian liberation/contextual theology…………. 98 3.3 Palestinian Liberation Hermeneutics……………………………………………….102 3.4 Peace and Justice……………………………………………………………………109 3.4.1 The prophetic appeal to Justice……………………………………………….109 3.4.2 The adoption of Utilitarian ideals…………………………………………….111 3.5 Election and Universalism………………………………………………………….113 3.6 The Problem of Land……………………………………………………….............116 3.7 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………119 CHAPTER 4 - The Politics and Praxis of Naim Ateek and Sabeel.................................120 4.1 Sabeel and Jerusalem……………………………………………………………… 120 4.2 Sabeel and the Peace Process…………………………………………………....... 130 4.3 The One-State solution…………………………………………………………......137 4.4 Sabeel and Human Rights…………………………………………………………. 138 4.5 Sabeel and Women’s Rights………………………………………………………..141 4.6 Sabeel and a Christian theology of Islam………………………………………… 142 4.7 Sabeel’s theology of engagement with the State of Israel………………………… 145 4.8 The Palestinian Jesus: using crucifixion imagery amidst accusations of deicide… 146 4.9 Use of ‘liberation theology’ in the politics of the Palestine-Israel struggle……… 152 4.10 Sabeel and the question of Divestment……………………………………………155 4.10.1 Sabeel’s Divestment Strategy……………………………………...............158 4.10.2 Responses to Sabeel’s call for Divestment………………………………...161 4.11 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………...165 CHAPTER 5 - Contextual Theology in Palestine: The Theological and Political Practise of Dr. Mitri Raheb...........................................................................................................166 5.1 Palestinian Contextual Theology: The Roots……………………………………....168 5.1.1 ‘Palestinianism’ as an integral part of Biblical Interpretation………………..170 5.1.2 Raheb’s Contextual Theology………………………………………………...171 5.1.3 Raheb’s Cultural Theology and Praxis……………………………………….174 5.1.4 Raheb and Holocaust (post-Auschwitz) Theology in the West………………176 5.1.5 Raheb and the ‘fragmentation’ of the worldwide Christian community…… 178 5.1.6 Raheb’s conception of ‘minority status’ in the Biblical context……………..179 5.1.7 Raheb’s definition of ‘Christian Mission’…………………………………....179 5.2 Raheb s Critical Theological Concepts…………………………………………… 180 5.2.1 The Bible and Palestinian Christians…………………………………………180 5.2.3 Raheb’s reading of the Prophet Jonah……………………………………… 186 5.2.4 Raheb’s hermeneutic use of ‘Law and the Gospel’…………………………..186 5.2.5 Raheb’s interpretation of the concept of ‘Election’…………………………..189 5.2.6 Raheb and Israeli ‘Election’…………………………………………………..191 5.2.7 Raheb and ‘Land’ in the Bible…………………………………………..........193 5.3 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….197 CHAPTER 6 - Conclusions.............................................................................................200 6.1 Relevance to Palestinian Christians…………………………………………………201 6.2 The value to Muslims……………………………………………………………… 205 viii 6.3 Dependence on the West…………………………………………………………… 206 6.4 The difference between liberation and contextual theologies………………………208 6.5 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..216 Appendix A: Religious composition of the Middle Eastern region.................................217 Appendix B: Palestinian loss of land 1946 to 2000.........................................................218 Appendix C: The Allon Plan, July 1967..........................................................................219 Appendix D: The Old City of Jerusalem.........................................................................220 Appendix E: Palestinian West Bank cities and Israeli settlement policies......................221 Bibliography....................................................................................................................222 ix