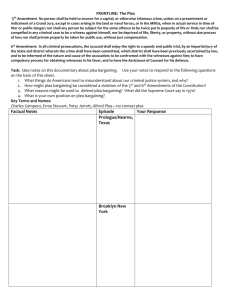

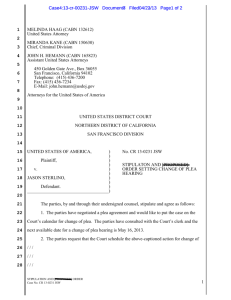

Plea Bargain

advertisement