Global Integration versus Local Flexibility

advertisement

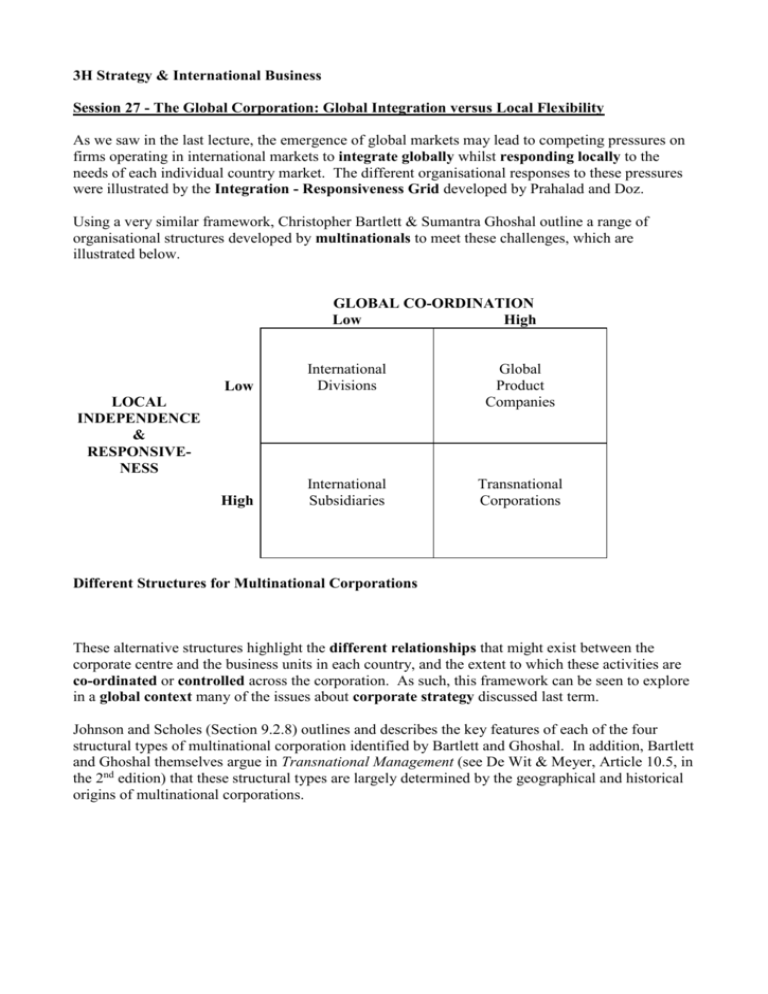

3H Strategy & International Business Session 27 - The Global Corporation: Global Integration versus Local Flexibility As we saw in the last lecture, the emergence of global markets may lead to competing pressures on firms operating in international markets to integrate globally whilst responding locally to the needs of each individual country market. The different organisational responses to these pressures were illustrated by the Integration - Responsiveness Grid developed by Prahalad and Doz. Using a very similar framework, Christopher Bartlett & Sumantra Ghoshal outline a range of organisational structures developed by multinationals to meet these challenges, which are illustrated below. GLOBAL CO-ORDINATION Low High Low International Divisions Global Product Companies High International Subsidiaries Transnational Corporations LOCAL INDEPENDENCE & RESPONSIVENESS Different Structures for Multinational Corporations These alternative structures highlight the different relationships that might exist between the corporate centre and the business units in each country, and the extent to which these activities are co-ordinated or controlled across the corporation. As such, this framework can be seen to explore in a global context many of the issues about corporate strategy discussed last term. Johnson and Scholes (Section 9.2.8) outlines and describes the key features of each of the four structural types of multinational corporation identified by Bartlett and Ghoshal. In addition, Bartlett and Ghoshal themselves argue in Transnational Management (see De Wit & Meyer, Article 10.5, in the 2nd edition) that these structural types are largely determined by the geographical and historical origins of multinational corporations. International Divisions This form of multinational structure has existed for many years, with many American corporations having adopted this approach in the past, often in their growth period of the 1940s and 1950s, reflecting the relatively large size of their domestic market. The structure is appropriate were there is little requirement for global co-ordination and little need to tailor products to local requirements. International Subsidiaries Many organisations are structured around international subsidiaries that respond more closely to the needs of the local market, often at the expense of control from the centre and a uniform organisational structure. Many European companies adopted such structures early in their development in the 1920s and 1930s, due to the relatively small size of their home markets, and the problems of communication and control across far-flung markets. However, whilst this structure has been appropriate in the past, as global competition becomes more intense, there may now be a need to look to greater global integration. Global Product Companies The need for greater global integration has seen many multinationals moving towards global product structures, with product divisions integrating activities on a world-wide basis from component supply, through manufacturing, to research and development. This has been a typical evolution for Japanese companies who have developed from direct exporting to the location of production activities in key local markets, frequently during the 1970s and 1980s. This structure creates many opportunities to achieve cost efficiencies and transfer resources that are dependent upon sophisticated planning and control systems. However, the pressures to respond to local needs seem to be increasing in many global markets. Transnational Corporations For Bartlett and Ghoshal, the increasing pressures of global competition upon companies to both globally co-ordinate activities and respond to local needs has led to the emergence of the transnational organisation. In one sense, the traditional multinational structures of the USA, Europe and Japan are seen to be converging upon a new organisational structure that depends upon an integrated network of interdependent resources. This is also a theme explored by Samuel Humes in his book, Managing the Multinational. The way in which such transnational organisations are structured and operate are discussed below. As an illustration of how multinationals might also move between these different organisational types, it is worth reading 3M’s Structures for Europe in Johnson and Scholes (Illustration 9.3, pp. 418-419). In broad terms, 3M moved from an international divisions structure to international subsidiaries in the 1950s. By the late 1970s, the company sought greater co-ordination of activities across Europe, starting with research and development. Through the 1980s further change was considered, with the company eventually moving to a global product company structure in the early 1990s. The Burmah Castrol Chemicals Group case study from last term (J & S pp 935-958) also shows how the grid can be used in practice to plot how the global/local pressures might raise questions about the need to change organisational structure. Creating the Transnational Corporation According to Bartlett and Ghoshal’s article, Managing Across Borders (De Wit & Meyer, 1st edition), the increasing interdependence of national markets is leading many multinational organisations to adopt transnational structures, as outlined above. They identify several key dimensions of these emerging structures and the challenges that they face, stressing the need for firms to structure along three dimensions as they face increasing global pressures: global functional management - to encourage the transfer of learning and core competencies across the organisation, allowing managers to accumulate knowledge and skills and be able to apply them on a world-wide basis; global business management - with managers with global product responsibilities championing the search for world-wide efficiency and integration; geographic management - within each country, responsive to local market requirements, sensing these needs and feeding them into the corporation as a whole. This leads to a much more complex, multidimensional structure than in traditional multinationals. Bartlett and Ghoshal argue that this places particular demands upon the managers within the organisation to be able to develop new capabilities to meet these challenges. In particular, they argue that these challenges require managers to tackle oversimplifications, with the new transnational structures exhibiting significant differences with the past: with uniform/symmetrical organisational structures being replaced by differentiation - with different structures and managerial control arrangements in different parts of the organisation; with a move away from the dependence of business units on a strong centre or the alternative of independence of subsidiaries - instead the corporation moves towards interdependence, with collaboration and co-operation encouraged between business units and with the centre; with traditional control arrangements moving towards co-ordination and co-option, stressing the “people” aspects and creating differing approaches depending upon the strategic significance of the particular business unit. Above all, Bartlett and Ghoshal stress that the achievement of this different approach is less about the structure of the organisation, but more about a “mind matrix” of the managers who make up the organisation. This is similar to the argument raised by Kenichi Ohmae about the thinking of global managers - “think global - act local” and the need for “insiderisation”. Johnson and Scholes discuss some of the practical issues that might be involved (see Section 9.2.8, point 4 pp. 420-422). Finally, Bartlett and Ghoshal’s article on Transnational Management outlines the changing organisational structure patterns implied by the wider discussion, particularly the problems of matrix structures. Whilst not being specific, they also build on the features outlined above to argue for multidimensional perspectives; distributed, interdependent capabilities; and a flexible, integrative process. Together these argue for an integrated network model for the transnational.