Lecture Notes - Durham University Community

advertisement

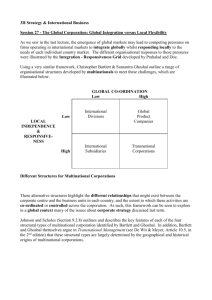

4 M Eng Strategic & Change Management Sessions 6: The Global Corporation: The Emergence of the Global Firm Many of you will have had the opportunity to travel across the globe, what products seem to be ubiquitous? The list is likely to include many well-known consumer brands like Coca-Cola, Sony, Nike, Levi’s etc. In many cases similar types of customers buy these products, why? Perhaps because they are exposed to similar influences - many people can now travel across the world and experiences become diffused; communications from the TV to the Internet; common cultural experiences like music and bands- T.V. etc. Some authors argue that these are the factors that underpin the emergence of a global market: Global Markets - Standardisation of Products (Levitt) “A powerful force drives the world towards a converging commonality… technology” Customers needs and interests are becoming increasingly homogenous People are willing to sacrifice preferences in product features, functions, design etc. for lower prices at high, but standardised quality Substantial economies of scale in production and marketing can be achieved through supplying global markets In such circumstances, argues Levitt, companies need to operate globally by delivering standardised products, to gain a low cost position through economies of scale. Others disagree, pointing to a more complex picture, with divergence apparent in some markets, as well as convergence in others. The European brewing industry still exhibits differences in brands and distribution systems between countries. Global Markets - The Myth of Standardisation (Douglas & Wind) Homogenisation of customer needs and interests? Evidence of homogenisation is not universal Growth of intra-country segmentation Universal preference for low price at an acceptable quality? Lack of evidence of increased price sensitivity (but may be changing in late 1990s) Vulnerability of low price positioning strategy Standardisation means under price/quality in one market but over price/quality in another Economies of scale in production and marketing? Flexible manufacturing can mean lower minimum efficient scale Production costs are often a minor part of total cost Douglas & Wind, amongst others, argue that differing strategies are needed - low price/standardised products may not be what customers want. Standard product for a small segment across a number of countries may mean that larger segments within each market are ignored. Seeking economies of scale to achieve low cost may not be the right or only response, indeed technology can remove as well as create economies of scale e.g. flexible manufacturing: “The trend towards global products and services is not all in one direction and the implications for organisations are therefore not just about achieving global product standardisation. There is still room for national differences in tastes and the products and services we buy and consume.” The picture may be more complex than Levitt painted in his article. The emerging world of the global market place may not be one consisting only of consumers exhibiting homogenised tastes, willing to buy globally standardised products. There are clearly still markets which exhibit heterogeneity in conditions and tastes from country to country, which require a variety of strategic responses. Further, it might not just be an issue of homogeneous versus heterogeneous markets. The nature of the competition itself might also be important. Mapping the Complexity of Global Pressures and Competition Consequently, the picture may be more complex than Levitt would have us believe. Further, it might not just be an issue of homogeneous versus heterogeneous markets. The nature of competition may also be important. Prahalad & Doz identify conflicting pressures on firms within industries, some pushing the firm towards global integration, others towards local responsiveness. Pressures for Global Integration Importance of multinational customers Importance of multinational competitors Investment intensity Technology intensity Pressure for cost reduction Universal needs Access to raw materials versus Need for Local Responsiveness Differences in customer needs Differences in distribution Need for substitutes & product adaptation Market structure Government demands These pressures will have different implications for the strategy of firms, depending on their relative importance. In assessing the competing pressures on organisations, the industries/markets in which they operate can be displayed graphically, and movement indicated over time: The Integration - Responsiveness Grid High Global Businesses Global Integration Pressures Multifocal Businesses Locally Responsive Businesses Low Low Local Responsiveness Pressures High Where there are strong pressures to be locally responsive and the pressures to integrate globally are low, then businesses need to have different strategies to meet the needs of each country market - the corporation consisting of a series of locally responsive businesses. Alternatively, where the pressures to integrate globally are high and there are few pressures to be locally responsive, a global business approach, similar to that outlined by Levitt, is possible. Where the pressures to be both globally integrated and locally responsive are important, then a multi-focal business approach is needed. As well as plotting the current position of the business, the Integration - Responsiveness Grid can be used to plot how the pressures change over time, so moving the business around the grid. Prahalad and Doz go on to stress that it is not just the characteristics of the industry/market that matter. Even if the industry structure indicates a requirement for local responsiveness, the ability of international competitors to use global cash flows to underpin their strategies may force others to respond on a more global basis. Consequently, they conclude that the strategic intentions of competitors are important. Becoming Global The central question for organisations facing the potential pressures of globalisation is: “If competition is, or may become more global, but the patterns are not simplistic, what are the implications for a firm's strategy and organisation?” Kenichi Ohmae’s view of how organisations can respond to these challenges lies at the heart of the video The Borderless World. He outlines an organisational response that proposes five stages of globalisation. This is illustrated by examining how the business system needs to change as the organisation becomes increasingly global. The business system approach adopted by Ohmae is a variant of the value chain concept (a la Porter - though this is not really a surprise because Porter pinched it from McKinsey!). Ohmae describes his stages approach in terms of the reconfiguration of the business system: Ohmae argues that as the organisation seeks to internationalise, it increasingly transfers key activities into its main foreign markets. Thus the stages can be outlined: Stage 1 - here the firm commences to sell outside its home market through direct export activities, often relying on the services of a local agent within its new markets; Stage 2 - increasing involvement in its main foreign markets leads the firm to establish local sales and marketing operations in order to more closely understand the needs of its customers in these markets; Stage 3 - sees the firm adding local manufacturing and service operations to its main foreign activities, with the ability to tailor products and services more closely to local market requirements; Stage 4 - this complete insiderisation stage sees the multinational firm replicating all the main activities of its home base business system within its major foreign markets, allowing these operations to fully tailor their strategies to the needs of local customers; Stage 5 - in this final stage, the global firm integrates some activities on a global basis to prevent fragmentation of the business as a whole, whilst still meeting the needs of local customers. Ohmae sees the emerging global corporation as more than just a company increasing the value of its export to sales ratio. It is about growing organisational sophistication; increasing operational involvement in target markets through transfer of activities; the ability to deliver and support more sophisticated products to these markets and a desire to operate across all areas of the globe. For Ohmae, the creation of a global firm is about more than just increasing the proportion of the company’s exports. It is about a growing organisational sophistication, increasing operational involvement in target markets through transfer of activities, the ability to deliver and support more sophisticated products within these markets, and a desire to operate across all areas of the globe. In his article, “Managing in a Borderless World” he outlines some of the challenges facing managers who wish to create a global firm. Ohmae sees the world’s markets becoming increasingly interdependent, with barriers falling between them. His response to these emerging global markets is not to suggest global standardisation, which he argues will average away important customer requirements. For Ohmae, becoming a global firm involves insiderisation - being able to understand and respond to local customer needs by tailoring the business system in each country to meet these requirements. The structure of the organisation or the activities that it performs are not the end of the story. The critical issue for managers is the ability to think globally - valuing the customer on the other side of the globe equally with the customer in the next street. This has led him to describe globalisation in terms of the “globalisation of the mind” - being able to think globally, but act locally in order to meet the requirements of your customers, wherever they are located. Interestingly, when examining globalisation, Porter (in The Competitive Advantage of Nations, 1990, Chapter 2) also returns to the value chain to explain the implications for strategy. In particular, he stresses that the pressures for global integration/local responsiveness might affect different activities in the value chain in different ways. Upstream activities may face pressures for global integration to gain cost advantages, where downstream activities, closer to the customer, may need to respond more to local market pressures. This will lead to a series of issues relating to the configuration and co-ordination of value activities: Configuration - Geographically concentrated or dispersed Co-ordination - Highly co-ordinated or independent However, whilst there are similarities of approach here, we shall see in the next session that Porter disagrees with Ohmae and others on other aspects of globalisation. The Emergence of the Transnational Corporation Earlier, we saw that the emergence of global markets may lead to competing pressures on firms operating in international markets to integrate globally whilst responding locally to the needs of each individual country market. The different organisational responses to these pressures were illustrated by the Integration - Responsiveness Grid developed by Prahalad and Doz. Using a very similar framework, Christopher Bartlett & Sumantra Ghoshal outline a range of organisational structures developed by multinationals to meet these challenges, which are illustrated below. GLOBAL CO-ORDINATION Low High Low International Divisions Global Product Companies High International Subsidiaries Transnational Corporations LOCAL INDEPENDENCE & RESPONSIVENESS Different Structures for Multinational Corporations These alternative structures highlight the different relationships that might exist between the corporate centre and the business units in each country, and the extent to which these activities are co-ordinated or controlled across the corporation. As such, this framework can be seen to explore in a global context many of the issues about corporate strategy discussed last term. Johnson and Scholes (Section 9.2.8) outlines and describes the key features of each of the four structural types of multinational corporation identified by Bartlett and Ghoshal. In addition, Bartlett and Ghoshal themselves argue in Transnational Management that these structural types are largely determined by the geographical and historical origins of multinational corporations. International Divisions This form of multinational structure has existed for many years, with many American corporations having adopted this approach in the past, often in their growth period of the 1940s and 1950s, reflecting the relatively large size of their domestic market. The structure is appropriate were there is little requirement for global co-ordination and little need to tailor products to local requirements. International Subsidiaries Many organisations are structured around international subsidiaries that respond more closely to the needs of the local market, often at the expense of control from the centre and a uniform organisational structure. Many European companies adopted such structures early in their development in the 1920s and 1930s, due to the relatively small size of their home markets, and the problems of communication and control across far-flung markets. However, whilst this structure has been appropriate in the past, as global competition becomes more intense, there may now be a need to look to greater global integration. Global Product Companies The need for greater global integration has seen many multinationals moving towards global product structures, with product divisions integrating activities on a world-wide basis from component supply, through manufacturing, to research and development. This has been a typical evolution for Japanese companies who have developed from direct exporting to the location of production activities in key local markets, frequently during the 1970s and 1980s. This structure creates many opportunities to achieve cost efficiencies and transfer resources that are dependent upon sophisticated planning and control systems. However, the pressures to respond to local needs seem to be increasing in many global markets. Transnational Corporations For Bartlett and Ghoshal, the increasing pressures of global competition upon companies to both globally co-ordinate activities and respond to local needs has led to the emergence of the transnational organisation. In one sense, the traditional multinational structures of the USA, Europe and Japan are seen to be converging upon a new organisational structure that depends upon an integrated network of interdependent resources. This is also a theme explored by Samuel Humes in his book, Managing the Multinational. The way in which such transnational organisations are structured and operate are discussed below. As an illustration of how multinationals might also move between these different organisational types, it is worth reading 3M’s Structures for Europe in Johnson and Scholes (Illustration 9.3, pp. 418-419). In broad terms, 3M moved from an international divisions structure to international subsidiaries in the 1950s. By the late 1970s, the company sought greater co-ordination of activities across Europe, starting with research and development. Through the 1980s further change was considered, with the company eventually moving to a global product company structure in the early 1990s. The Burmah Castrol Chemicals Group case study from last term (J & S pp 935-958) also shows how the grid can be used in practice to plot how the global/local pressures might raise questions about the need to change organisational structure. Bartlett and Ghoshal argue that the increasing interdependence of national markets is leading many multinational organisations to adopt transnational structures, as outlined above. They identify several key dimensions of these emerging structures and the challenges that they face, stressing the need for firms to structure along three dimensions as they face increasing global pressures: global functional management - to encourage the transfer of learning and core competencies across the organisation, allowing managers to accumulate knowledge and skills and be able to apply them on a world-wide basis; global business management - with managers with global product responsibilities championing the search for world-wide efficiency and integration; geographic management - within each country, responsive to local market requirements, sensing these needs and feeding them into the corporation as a whole. This leads to a much more complex, multidimensional structure than in traditional multinationals. Bartlett and Ghoshal go on to argue that this places particular demands upon the managers within the organisation to be able to develop new capabilities to meet these challenges. In particular, they argue that these challenges require managers to tackle oversimplifications, with the new transnational structures exhibiting significant differences with the past: with uniform/symmetrical organisational structures being replaced by differentiation - with different structures and managerial control arrangements in different parts of the organisation; with a move away from the dependence of business units on a strong centre or the alternative of independence of subsidiaries - instead the corporation moves towards interdependence, with collaboration and co-operation encouraged between business units and with the centre; with traditional control arrangements moving towards co-ordination and co-option, stressing the “people” aspects and creating differing approaches depending upon the strategic significance of the particular business unit. Above all, Bartlett and Ghoshal stress that the achievement of this different approach is less about the structure of the organisation, but more about a “mind matrix” of the managers who make up the organisation. This is similar to the argument raised by Kenichi Ohmae about the thinking of global managers - “think global - act local” and the need for “insiderisation”. Johnson and Scholes discuss some of the practical issues that might be involved (see Section 9.2.8, point 4 pp. 420-422). Finally, Bartlett and Ghoshal outline the changing organisational structure patterns implied by the wider discussion, particularly the problems of matrix structures. Whilst not being specific, they also build on the features outlined above to argue for multidimensional perspectives; distributed, interdependent capabilities; and a flexible, integrative process. Together these argue for an integrated network model for the transnational.