Basic Reproductive Biology

advertisement

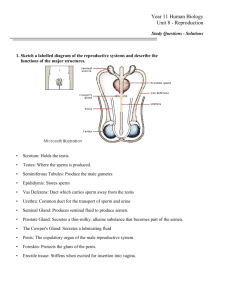

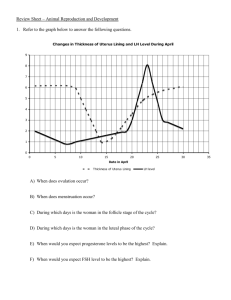

The Reproductive System A Quick Review of the Reproductive Anatomy Our overview of the reproductive system begins at the external genital area— or vulva— which runs from the pubic area downward to the rectum. Two folds of fatty, fleshy tissue surround the entrance to the vagina and the urinary opening: the labia majora, or outer folds, and the labia minora, or inner folds, located under the labia majora. The clitoris, is a relatively short organ (less than one inch long), shielded by a hood of flesh. When stimulated sexually, the clitoris can become erect like a man's penis. The hymen, a thin membrane protecting the entrance of the vagina, stretches when you insert a tampon or have intercourse. From this point onward, the reproductive system leads deeper and deeper into the body. The Vagina The vagina is a muscular, ridged sheath connecting the external genitals to the uterus, where the embryo grows into a fetus during pregnancy. In the reproductive process, the vagina functions as a two-way street, accepting the penis and sperm during intercourse and roughly nine months later, serving as the avenue of birth through which the new baby enters the world . The Cervix The vagina ends at the cervix, the lower portion or neck of the uterus. Like the vagina, the cervix has dual reproductive functions. After intercourse, sperm ejaculated in the vagina pass through the cervix, then proceed through the uterus to the fallopian tubes where, if a sperm encounters an ovum (egg), conception occurs. The cervix is lined with mucus, the quality and quantity of which is governed by monthly fluctuations in the levels of the two principle sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone. When estrogen levels are low, the mucus tends to be thick and sparse, which makes it difficult for sperm to reach the fallopian tubes. But when an egg is ready for fertilization and estrogen levels are high the mucus then becomes thin and slippery, offering a much more friendly environment to sperm as they struggle towards their goal. (This phenomenon is employed by birth control pills, shots and implants. One of the ways they prevent conception is to render the cervical mucus thick, sparse, and hostile to sperm.) HOW THE SYSTEM FITS TOGETHER Deep within the pelvic region lie the specialized female organs that make conception and pregnancy possible. In this cutaway view, you can see how the cervix acts as the gateway between the vagina and the uterus, where an egg, if fertilized, will be nurtured and, over the course of nine months, grow to be a newborn child. Riding atop the uterus are the two ovaries, storehouse of all a woman's eggs. The fallopian tubes, where fertilization by a sperm will occur, are narrow conduits connecting each ovary to the uterus. Later, at the end of pregnancy, the cervix acts as the passage through which the baby exits the uterus into the vagina. The cervical canal expands to roughly 50 times its normal width in order to accommodate the passage of the baby during birth. The Uterus The uterus is the muscular organ which holds the developing baby during the nine months after conception. Like the cervical canal, the uterus expands considerably during the reproductive process. In fact, the organ grows to from 10 to 20 times its normal size during pregnancy. A CLOSER LOOK AT THE UTERUS Note the thick muscular walls—crucial when the baby is ready for delivery—and the lush inner lining, or endometrium, which nurtures the developing egg. From this angle, you can also see how the fallopian tubes cradle the ovaries in their feathery fimbria, ready to conduct a mature egg away from the ovary and on into the uterus. Each month the uterus goes through a cyclical change, first building up its endometrium or inner lining to receive a fertilized egg, then, if conception does not occur, shedding the unused tissue through the vagina in the monthly process called menstruation. The monthly development of the endometrium is initiated by estrogen from the ovary. Following ovulation the endometrium is supported by both estrogen and progesterone. When estrogen and progesterone levels decline near the end of the cycle, menstrual bleeding begins. The Fallopian Tubes Beyond the uterus, the fallopian tubes connect the rest of the system to the ultimate source of the eggs, the two ovaries. Each of these tubes is roughly five inches long and ranges in width from about one inch at the end next to the ovary, to the diameter of a strand of thin spaghetti. The trumpet-shaped part near the ovary has about 20 to 25 feathery projections called fimbria, one of which is attached to the ovary. It is the fimbria that each month urge an egg to exit the ovary and begin its trip towards the uterus. The Ovaries The ovaries are a woman's storehouse of egg cells. They are among the first organs to be formed as a female baby develops in the uterus. At the 20-week mark, the structures that will become the ovaries house roughly 6 to 7 million potential egg cells. From that point on, the number begins to decrease rapidly. A newborn infant has between 1 million to 2 million egg cells. By puberty the number has plummeted to 300,000. For every egg that matures and undergoes ovulation, roughly a thousand will fail, so that by menopause, only a few thousand remain. During the course of an average reproductive lifespan, roughly 300 mature eggs are produced for potential conception. FROM FOLLICLE TO “YELLOW BODY” Host to a lifetime supply of eggs, the ovaries each month launch about 20 contenders towards potential conception. Each ripens in a supporting follicle, growth of which is triggered by the aptly named “follicle-stimulating hormone.” In turn, the winning follicle gives off increasing amounts of the hormone estrogen, which prepares the lining of the uterus for pregnancy. Once a mature egg has begun its trip through the fallopian tube, remnants of the winning follicle form the corpus luteum, or “yellow body.” Progesterone from the corpus luteum halts development of the remaining follicles and brings the lining of the uterus to peak preparedness. The egg cells remain inactive until puberty, when the reproductive system is activated by the secretion of Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing Hormone (LH) from the pituitary. Then, each month several egg cells, each encased in a sac called a follicle, begin to ripen. Responding selectively to the FSH, one follicle becomes dominant while the others shrink away. The egg within the dominant follicle continues ripening to maturity; and as it grows the cells in the surrounding follicle produce more and more estrogen each day. Then, at mid-cycle, the follicle ruptures and the egg is released (ovulation). It exits the ovary and enters the adjacent fallopian tube to be either fertilized or, if conception fails to occur, expelled from the body during menstruation. If fertilization is to occur, it usually happens when the egg's journey is about one-third complete. Once a sperm unites with the egg, specific changes occur at the egg cell membrane to block a second fertilization. The Corpus Luteum The fertilized egg (zygote) then continues on its journey through the fallopian tube. Along the way the embryo begins to develop; first into a solid ball of cells called a morula, and then into a hollow mass of perhaps 100 cells called a blastocyst. About four or five days after fertilization, the blastocyst enters the uterus and implants itself on the endometrium, which has been primed by the sex hormones to accept and nurture it. Meanwhile, the follicle that held the egg still has a critical role to play. First it shrinks markedly, then begins to accumulate fatty substances, or lipids, that give it a yellowish tinge. The resulting structure, now called the corpus luteum (yellow body), produces progesterone and estradiol, two of the hormones critical to reproduction. In a non-pregnant woman, the corpus luteum lasts for about 14 days, after which it shrinks and dries up, eventually becoming a speck of fibrous scar tissue. If conception occurs, however, a hormone from the developing placenta (chorionic gonadotropin), which surrounds the baby in the uterus, stimulates the corpus luteum to maintain its production of progesterone during the first trimester of pregnancy. Early Embryology The diagram given below illustrates the first 5-6 days of pregnancy in humans. The fertilized egg is called a zygote. This zygote divides to form a morula (ball of cells) by day three. As cell division continues, the resulting cells become smaller and smaller. The early cell divisions, which are more or less equal, are called cleavage divisions. Eventually, the morula forms a hollow ball of cells called a blastocyst. The blastocyst has two parts; the inner cell mass (which becomes the actual embryo), and the trophoblast (which becomes the fetal contribution to the placenta). The blastocyst implants in the endometrium of the uterus to establish the pregnancy. Label the diagram given below with all of the terms written in bold in this paragraph. Male Reproduction In simple terms, reproduction is the process by which organisms create descendants. This miracle is a characteristic that all living things have in common and sets them apart from nonliving things. But even though the reproductive system is essential to keeping a species alive, it is not essential to keeping an individual alive. In human reproduction, two kinds of sex cells or gametes are involved. Sperm, the male gamete, and an egg or ovum, the female gamete must meet in the female reproductive system to create a new individual. For reproduction to occur, both the female and male reproductive systems are essential. While both the female and male reproductive systems are involved with producing, nourishing and transporting either the egg or sperm, they are different in shape and structure. The male has reproductive organs, or genitals, that are both inside and outside the pelvis, while the female has reproductive organs entirely within the pelvis. The male reproductive system consists of the testes and a series of ducts and glands. Sperm are produced in the testes and are transported through the reproductive ducts. These ducts include the epididymis, ductus deferens, ejaculatory duct and urethra. The reproductive glands produce secretions that become part of semen, the fluid that is ejaculated from the urethra. These glands include the seminal vesicles, prostate gland, and bulbourethral glands. MALE REPRODUCTIVE ANATOMY Testes The testes (singular, testis) are located in the scrotum (a sac of skin between the upper thighs). In the male fetus, the testes develop near the kidneys, then descend into the scrotum just before birth. Each testis is about 1 1/2 inches long by 1 inch wide. The testes contain long coiled tubes called the seminiferous tubules where spermatogenesis occurs utilizing the process of meiosis. Testosterone is produced in the testes by endocrine tissue called “Leydig cells.” Testosterone stimulates spermatogenesis, growth of the male reproductive tract and the development of secondary sex characteristics beginning at puberty. Scrotum The two testicles are each held in a fleshy sac called the scrotum. The major function of the scrotal sac is to keep the testes cooler than thirty-seven degrees Celsius (ninety-eight point six degrees Fahrenheit). The external appearance of the scrotum varies at different times in the same individual depending upon temperature and the subsequent contraction or relaxation of two muscles. These two muscles contract involuntarily when it is cold to move the testes closer to the heat of the body in the pelvic region. This causes the scrotum to appear tightly wrinkled. On the contrary, they relax in warm temperatures causing the testes to lower and the scrotum to become flaccid. The temperature of the testes is maintained at about thirty-five degrees Celsius (ninety-five degrees Fahrenheit), which is below normal body temperature. Temperature has to be lower than normal in order for spermatogenesis (sperm production) to take place. Seminiferous Tubules Each testis contains over 100 yards of tightly packed seminiferous tubules. Around 90% of the weight of each testes consists of seminiferous tubules. The seminiferous tubules are the functional units of the testis, where spermatogenisis takes place. Once the sperm are produced, they are moved from the seminiferous tubules into the rete testis for further maturation. Interstitial Cells (Cells of Leydig) In between the seminiferous tubules within the testes, are instititial cells, or, Cells of Leydig. Interstitial cells are stimulated by LH from the anterior pituitary. In response they secrete male hormones – most importantly testosterone. Sertoli Cells Sertoli cells are found at the innermost lining of the seminiferous tubules. Their main function is to nurture the developing sperm cells through the stages of spermatogenesis. These cells surround the immature sperm cells (spermatids) and support the process of maturation. While the Sertoli cells are wrapped around the spermatids, the spermatids shed cytoplasm and develop a flagellum. Because of this function, Sertoli cells are also called "nurse cells.” Sertoli cells are activated by FSH from the anterior pituitary. Efferent ductules The sperm are transported out of the testis and into the epididymis through a series of efferent ductules. Blood Supply The testes receive blood through the testicular arteries (gonadal artery). Venous blood is drained by the testicular veins. The right testicular vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava. The left testicular vein drains into the left renal vein. Epididymis The seminiferous tubules join together to become the epididymis. The epididymis is a tube that is about 20 feet long that is coiled on the posterior surface of each testis. Within the epididymis the sperm complete their maturation and their flagella become functional. This is also a site to store sperm until the next ejaculation. Smooth muscle in the wall of the epididymis propels the sperm into the ductus deferens.. Vas Deferens (Ductus Deferens) The ductus (vas) deferens, also called sperm duct, or, spermatic deferens, extends from the epididymis in the scrotum on its own side into the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal. The inguinal canal is an opening in the abdominal wall for the spermatic cord (a connective tissue sheath that contains the ductus deferens, testicular blood vessels, and nerves. The smooth muscle layer of the ductus deferens contracts in waves of peristalsis during ejaculation. Seminal Vesicles The pair of seminal vesicles are posterior to the urinary bladder. They secrete a slightly alkaline fluid which helps regulate the pH of tubular contents as sperm cells travel to the outside. Seminal vesicle secretions also contain fructose that provides energy to sperm cells, and prostaglandins which stimulate muscular contractions within the female reproductive tract. Ejaculatory Ducts There are two ejaculatory ducts. Each receives sperm from the ductus deferens and the secretions of the seminal vesicle on its own side. Both ejaculatory ducts empty into the single urethra. Prostate Gland The prostate gland is a chestnut shaped organ that surrounds the proximal portion of the urethra. It is composed of many branched tubular glands , whose ducts open into the urethra. The prostate secretes a thin, milky fluid with an alkaline pH which helps to stabilize pH and to counteract the acidic environment of the vagina. Bulbourethral Glands The bulbourethral glands also called Cowper's glands are located below the prostate gland and empty into the urethra. The glands secrete a mucous-like fluid during sexual stimulation. It is thought to lubricate the head of the penis. However, most lubrication is provided by females during sexual intercourse. Penis The penis is an external genital organ. The distal end of the penis is called the glans penis and is covered with a fold of skin called the prepuce or foreskin. Within the penis are three masses of erectile tissue (corpus spongiosum (1) and corpus cavernosa (2). Each consists of a framework of smooth muscle and connective tissue that contains blood sinuses, which are large, irregular vascular channels. During an erection, arteries entering the penis dilate and the erectile tissue fills with blood. Insufficient dilation or low blood pressure will not sustain a normal erection. Urethra The urethra, which is the last part of the urinary tract, lies within the corpus spongiosum and its opening, known as the meatus, lies on the tip of the glans penis. It is both a passage for urine and for the ejaculation of semen.