Entrepreneurial role expectations in farming

advertisement

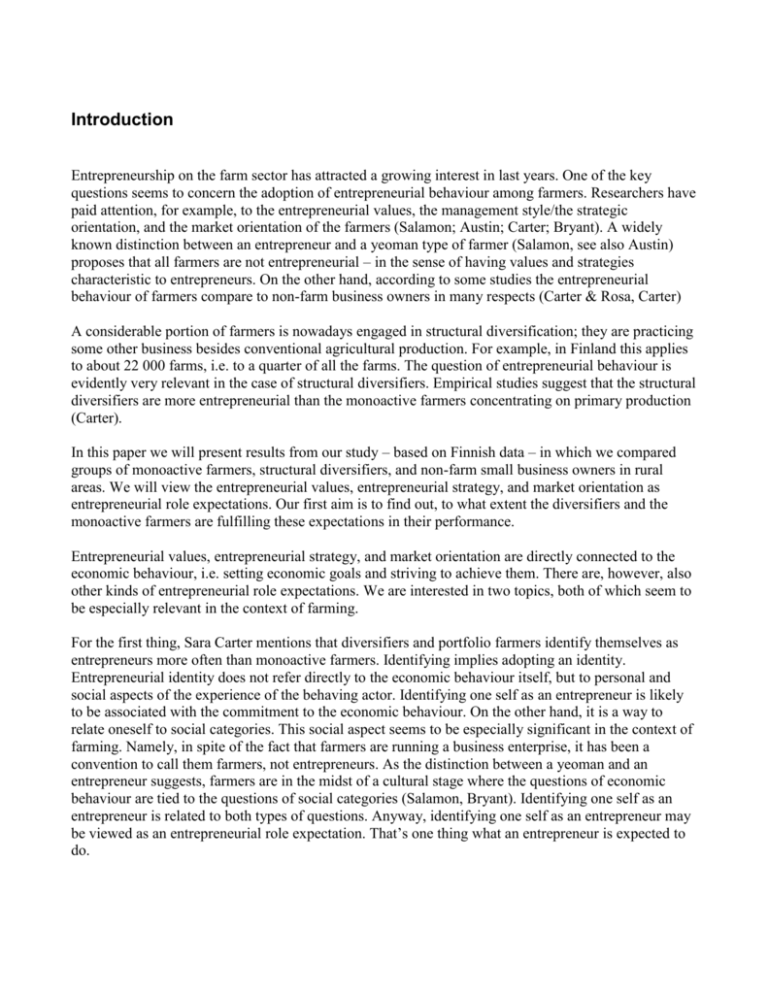

Introduction Entrepreneurship on the farm sector has attracted a growing interest in last years. One of the key questions seems to concern the adoption of entrepreneurial behaviour among farmers. Researchers have paid attention, for example, to the entrepreneurial values, the management style/the strategic orientation, and the market orientation of the farmers (Salamon; Austin; Carter; Bryant). A widely known distinction between an entrepreneur and a yeoman type of farmer (Salamon, see also Austin) proposes that all farmers are not entrepreneurial – in the sense of having values and strategies characteristic to entrepreneurs. On the other hand, according to some studies the entrepreneurial behaviour of farmers compare to non-farm business owners in many respects (Carter & Rosa, Carter) A considerable portion of farmers is nowadays engaged in structural diversification; they are practicing some other business besides conventional agricultural production. For example, in Finland this applies to about 22 000 farms, i.e. to a quarter of all the farms. The question of entrepreneurial behaviour is evidently very relevant in the case of structural diversifiers. Empirical studies suggest that the structural diversifiers are more entrepreneurial than the monoactive farmers concentrating on primary production (Carter). In this paper we will present results from our study – based on Finnish data – in which we compared groups of monoactive farmers, structural diversifiers, and non-farm small business owners in rural areas. We will view the entrepreneurial values, entrepreneurial strategy, and market orientation as entrepreneurial role expectations. Our first aim is to find out, to what extent the diversifiers and the monoactive farmers are fulfilling these expectations in their performance. Entrepreneurial values, entrepreneurial strategy, and market orientation are directly connected to the economic behaviour, i.e. setting economic goals and striving to achieve them. There are, however, also other kinds of entrepreneurial role expectations. We are interested in two topics, both of which seem to be especially relevant in the context of farming. For the first thing, Sara Carter mentions that diversifiers and portfolio farmers identify themselves as entrepreneurs more often than monoactive farmers. Identifying implies adopting an identity. Entrepreneurial identity does not refer directly to the economic behaviour itself, but to personal and social aspects of the experience of the behaving actor. Identifying one self as an entrepreneur is likely to be associated with the commitment to the economic behaviour. On the other hand, it is a way to relate oneself to social categories. This social aspect seems to be especially significant in the context of farming. Namely, in spite of the fact that farmers are running a business enterprise, it has been a convention to call them farmers, not entrepreneurs. As the distinction between a yeoman and an entrepreneur suggests, farmers are in the midst of a cultural stage where the questions of economic behaviour are tied to the questions of social categories (Salamon, Bryant). Identifying one self as an entrepreneur is related to both types of questions. Anyway, identifying one self as an entrepreneur may be viewed as an entrepreneurial role expectation. That’s one thing what an entrepreneur is expected to do. So we will also try to find out whether there are differences in entrepreneurial identification between the sample groups. Further, we will try to answer the question: What is the relation between entrepreneurial identification and the other role expectations that are associated with entrepreneurship more directly on the level of economic behaviour. In addition to entrepreneurial identification, we are interested in how the diversifiers and the monoactive farmers perceive and experience the success of their businesses. Entrepreneurship has been associated – not least in farming context (Salamon, Austin) – with the aim of maximizing the economic success. An economic aim is, like economic values, closely tied to the economic pursuit on the level of entrepreneurial behaviour. However, like entrepreneurial identification, the experience of success has also important psychological and social implications. It belongs not only to the practical order of economic striving, but also to the expressive order (Harre) of social beings, where pride, shame, guilt and other emotions of self-esteem are essential. Anyway, feelings of failure and pessimism are not in line with the ideal entrepreneurial performance, even if failure may be claimed to have also positive functions (Storey 1994, 78-79). Again, we will try to find out whether there are differences in the experience of success between the sample groups. Further, we will try to answer the question: What is the relation between the experience of success and the other role expectations that are associated with entrepreneurship more directly on the level of economic behaviour. In the following, we will first outline our general approach to studying entrepreneurial aspects of small business. After that we will present the operational concepts used in the empirical part of our study, and proceed to the methods and results. A social psychological perspective to the `entrepreneurial` in small business At least three types of definitions have been used for the term `entrepreneurship`. (See for example Cunningham & Lischeron 1991) Firstly, entrepreneurship has been understood to refer to starting and/or running a business enterprise. For example, in the small business research (Storey 1994), where on the focus of the study is the firm this kind of definition has been conventional. An entrepreneur is viewed simply as a founder or an owner-manager of a small firm. On the other hand, in the study of entrepreneurship (Kilby 1971; Casson 1982; Stevenson & Jarillo 1991) the focus has been more on the behaviour of the individual actor. Special attention has been directed to the search for such behaviour that would maximally utilise the opportunities for successful business. Consequently, the term entrepreneurship has been understood to refer to only certain kinds of behaviour, not to the founding or running a firm (as such) in general. Entrepreneurship has been defined, for example, as innovating, risk-taking, growth oriented, new opportunities searching behaviour. This kind of view, emphasising individual and his/her dynamic behaviour is applied also in the third type of definition, which suggests that entrepreneurship is not restricted to business ownership but refers also to other contexts. According to this type of definition, for example, employees or paid managers can be said to be entrepreneurs. Often, however, a distinguishing term like `corporate entrepreneurship` or `intrapreneurship` is used. In this paper we are interested in the context of small business ownership, therefore the third type of definition is not relevant for our purposes. In the context of small business, the first type of definition is a wide one, while the second is a narrow definition. Our understanding of entrepreneurship falls somewhere in the middle, representing a kind of synthesis of these to types. Definition of entrepreneurship is a controversial matter (Kilby 1971; Cunningham & Lischeron 1991). Not all scholars – and certainly not all small business owners – accept the claim that only some of the small business owners are entrepreneurs properly speaking. However, the distinction between a small business owner who manage a firm in a conservative way, with the aim of getting a living for him/herself and his/her family, and a proper entrepreneur with a dynamic, innovative, growth-oriented style (Carland et al 1984) is well established in the study of entrepreneurship. For our present purposes this distinction is significant because it implies the possibility of using a term `entrepreneurial` - in a sense of indicating the degree or “strength” of entrepreneurship in some connection. For example, the more innovative behaviour is more entrepreneurial than the less innovative behaviour. It is, of course, possible to think that the behaviour of some small business owners is “truly entrepreneurial” while some others do not behave entrepreneurial at all. But as well one might interpret the criteria which are used to distinguish entrepreneurs from other small business owners as aspects of the behaviour of small business owners, so that some of them may be thought to behave more entrepreneurial than the others, and also that the one and the same owner may behave more entrepreneurial in one aspect than in the other. In the study of entrepreneurship, the focus on the behaviour or action of the entrepreneur is motivated by theories concerned with the effects that successful entrepreneurship has on the wider economic system. Innovative and dynamic behaviour is associated with the growth of employment and general economics (Stevenson & Jarillo 1991). Behaviour on the level of starting and running firms is markedly the behaviour of individuals. Considering this, it is of no surprise that also psychological theories have been very prominent in the study of entrepreneurship (Brockhaus & Horwitz 1986; Wärneryd 1988; Cunningham & Lischeron 1991; Cromie 2000) The emphasis in the psychological theories has been on such individual attributes or dispositions that would explain the entrepreneurial behaviour. Typically these theories suggest that some relatively enduring and stable factor – personality trait, unconscious need, etc – inside the individual causes the behaviour needed for successful business (Hull et al 1980) This suggestion conforms to the popular idea that entrepreneurs have different kind of personality than other people. Psychological theories are intuitively (or culturally) appealing, but results from empirical research have been ambiguous (Hisrich 2000). According to the critical arguments one of the main weaknesses in psychological theories has been the assumption that entrepreneurial behaviour could be explained by individual dispositions without taking into account the situation in which the behaviour takes place. The situation consists of the economic and social environment and the interaction between the environment and the individual. Behaviour ought to be viewed as a function of all these elements. (Shaver 1995; Hisrich 2000; Chell 2000; Carsrud & Johnson 1989; Jenks 1965; Starr & McMillan 1991; Aldrich & Zimmer 1986; Greenfield et al 1979) In this paper we adopt a social psychological perspective emphasising the relation between the individual and the environment, and the significance of the situation or social context in which this relation is embedded. (compare Shaver 1995; Carsrud & Johnson 1989; Jenks 1965; Starr & McMillan 1991). We apply this general perspective with the help of the concept of role. As Leland Jenks (1965, 88-89) has pointed out, the concept of role emphasises an entrepreneur’s relation to other actors and to his/here situation, and further helps to designate such psychological aspects that are relevant to entrepreneurial activities. The idea of viewing entrepreneur’s behaviour from the viewpoint of role expectations is not a new one. Various sources for such expectations have been pointed out, including the very nature of the competitive business, other social actors in immediate environment, wider social networks, culture and society. (Jenks 1965; Kilby 1971, 27; Barth 1963, 6; Cochran 1965; Greenfield et al 1979; Aldrich & Zimmer 1986; Carsrud & Johnson 1989; Lerner et al 1997). Because of the multiplicity of sources, there are potentially many kinds of expectations. The problem for the research seems to be, after all, in deciding which kinds of expectations – psychological or other – are most relevant in the case of the entrepreneurship. As we already mentioned, entrepreneurship can be understood as an aspect of the behaviour of small business owners. From this perspective it is apt to say that small business ownership is a role, and entrepreneurship is – following Frederick Barth (1963) – an aspect of this role. It is difficult to solve the problem of relevance empirically, because one has to decide first what is meant with the entrepreneurial aspects, in order to identify those cases where the expectations are relevant. The decision must be based on theoretical arguments. Our solution to the problem of relevance is simple. We interpret those aspects of the role performance of a small business owner that in the research literature are associated with entrepreneurship as entrepreneurial role expectations. There are slightly differing views about the most relevant aspects in different fields of research and theoretical discourses. For example, the aspects emphasised as entrepreneurial are not necessary the same in the study of farming (Bryant, Salamon) and in the study of entrepreneurship. Research literature in itself is, perhaps, not a very literal or influential source of role expectations for small business owners. Anyway, one might assume that the theoretical generalizations reflect some essential features in the situations and wider contexts of small business owners, even though our solution leaves open the questions about exact or concrete sources of these expectations. Entrepreneurial role expectations concern the performance of a small business owner. They represent demands arising from the situation, demands that may be more or less compelling. The individual acting as a small business owner may not approve all of these expectations and consequently may not even try to fulfil them. But then he/she would not be called entrepreneurial. In western cultures, at least, small business owners mostly likely are aware of the existence of these kinds of expectations. We understand the role expectations to represent an external, generalized viewpoint to the performance of a small business owner. The internal, subjective viewpoint of the actor is represented in the perceptions and experiences of the individual. Instead of searching for supposedly enduring, crosssituational psychological attributes of the individual we concentrate on cognitions concerning the situation of running the business and the actors own performance in it (Baron 1998; Gatewood e al 1995). Further, since the focus of our study is on the performance associated with entrepreneurship, we are interested in the cognitions and experiences concerning particularly such performance. In this way the perceptions and experiences of the actor may be viewed as psychological counterparts for the entrepreneurial role expectations on the level of performing, telling how well – or to what extent – the actor is fulfilling these expectations. For example: if innovative behaviour is the expectation, so the individuals perception of the innovativeness of his/her own behaviour is a psychological counter-part for this performance, telling how well the expectation is being fulfilled judging from the subjective perspective of the actor. This interpretation does not necessarily imply that the individual would consciously be viewing him/herself as an actor attempting to fulfil some expectations, and certainly not that the individual would be mechanically following a given script in doing this. Individuals often do their own deliberations on such things (Billig 1987). The crucial point is that by viewing the psychological counterparts for the performance indicated in the entrepreneurial role expectations, as if they were responses to these expectations, we hope to be able to be sensitive to the situational relation between individual and his environment. It must be remembered that the role expectations typically include not only certain kinds of behaviours but also certain kinds of outcomes, and ways for the actor to relate him/herself to the behaviour. For example, in idealized cultural representations one can recognize an expectation that an innovatively behaving entrepreneur is committed to his/her work, believes optimistically in his/her success, and actually ends up to be successful. Especially in the psychological theories certain kinds of attitudes, values and beliefs are associated with the role of an entrepreneur. Often these values or beliefs are interpreted as attributes of the individual, not as aspects of a role that relates individual to the situation. Anyway, holding certain kind of attitudes, values and beliefs may be viewed as part of the entrepreneurial role performance and, like behavioural performance, may be approached through the subjective perspective of the actor. As a matter of fact, in the case of values and beliefs, subjective perspective seems especially valid. Entrepreneurial role expectations in farming In the following we will introduce a set of entrepreneurial role expectations we used in our study. Some of these points are emphasised in the entrepreneurial studies, some in the study of farming. The list is, by no means, meant to be comprehensive; other alternatives might be justified as well. As we already told in the introduction, at least three kinds of entrepreneurial role expectations concerning the economic striving has been paid attention to in the study of farming: entrepreneurial values, entrepreneurial strategy and market orientation. First we will shortly introduce these. We will also introduce a fourth expectations concerning personal control. Personal control is a factor perhaps most often associated with entrepreneurial behaviour in psychological study of entrepreneurship. After that we will shortly introduce the expectations of entrepreneurial identification and experiences success, which we mentioned, in the introduction, as special topics of our interests. Entrepreneurial values By entrepreneurial values we mean, in this connection, simply the basic values of economic individualism: financial gain and independence. Profit is a common sense aim in business, and the autonomy associated with managing a firm is a common sense condition for pursuing this aim. To value these things is entrepreneurial, especially when the economic aim is understood as maximizing the profit. In the psychological study of entrepreneurship several kinds of values have been thought to be important for entrepreneurs (Brockhaus 1982). For example, David McClelland (1961) in his widely known theory suggests that entrepreneurs value personal achievement more than else. How ever, the basic indicator of achievement is the profit, the financial gain. An entrepreneur may have different kinds of personal values, but in his/her business he/she is expected to prefer the economic values. Entrepreneurial strategy An entrepreneur has been portrayed as an agent of change (Casson 1982, 24) or a person in pursuit of opportunity (Stevenson & Jarillo 1991). These expressions emphasise a view that dynamic, innovative striving is essential in entrepreneurial behaviour. Risk-taking, aiming to the growth of the business, and innovating, are often associated with entrepreneurial behaviour (Kilby 1971; Stanworth & Curran; Carland et al 1984; Storey 1994; Schumpeter; Drucker 1985; Stevenson & Jarillo 1991). Also in the study of farming the entrepreneurial behaviour has been associated with initiative, risk-taking and growth-oriented strategic orientation (Salamon 1992; Austin et al 1996) Risk taking, innovation, and growth-orientation can be viewed as separate dimensions, but still they all represent a more general orientation, which we call entrepreneurial strategy. In many studies these behavioural expectations have been approached as personality traits (Mueller & Thomas 2000; Brockhaus & Horwitz 1986; Cromie 2000). In this study we are interested in how an actor perceives his/her own behaviour in terms of these expectations. Customer orientation In the study of entrepreneurship, the questions related to market and customers have typically been understood as dealing with the entrepreneur’s tasks (Kilby; Chen et al;) or social networks (Curran Vesala 1996). Since the focus has been on the individual, these questions have not received any special attention. How ever, the market and the customers form an essential part of the situation of an entrepreneur, and many basic activities in business relate to the market and the customers. As mentioned in the introduction, in the context of farming market orientation has been strongly associated with entrepreneurship. Market orientation in itself is a complex concept, often defined on the level of strategic aims and positions (Matsuno et al 2002) . For our purposes we use more simple concept `customer activeness`, which includes customer related behaviours like selling, marketing, and having conversations with the customers. Our proposition is that activeness in relation to customers is an important entrepreneurial role expectation, especially in the context of farming. Personal control -in farming research rare, even when measuring personality etc (skotit), ei noteerata, sen sijaan Vesala & Rantanen, osoitti kval. Tutk. Asian keskeisyyttä juuri manviljelijoille, vieläpä että yhteydessä nimenoman asiakassuhteseen ja markkin-areenaan, sen sijaan psykologisessa yrittäjystutkimuksessa nykyään suosituinpia, elei suosituin, Often an implicit but still fundamental assumption the study of entrepreneurship is that an entrepreneur controls the success of his/her business through his/her own decisions and actions. Numerous conceptualisations in psychology refer to this kind of personal control, many of them as perceived personal control (Greenberger et al 1988; Skinner 1996). In the study of entrepreneurship, lots of research has been done with the locus of control –concept introduced by Julian Rotter (1966), but also other conceptualisations has been used (for example Chen et al 1988). The main point is the assumption – widely shared in psychological literature (Skinner 1996) – that the belief in ones chances to control the way things go has beneficial consequences on the well being and motivation of the individual. In entrepreneurial studies personal control has been associated, for example, with success, persistence, and innovativeness of behaviour (Brockhaus & Horwitz 1986; Cromie 2000; Mueller & Thomas 2000; Mueller & Thomas ). In psychological theorizing the belief in personal control is typically viewed as generalized, cross-situational belief, which is first of all an attribute of the individual. However, it is possible to think that the most relevant for entrepreneurship is the belief in personal control particularly in the situation of ones own business (Gatewood e al 1995). In the research done on farming the concept of personal control has been rare. How ever, according to a qualitative study Kari Mikko Vesala and Teemu Rantanen (1999) the belief in personal control is one of the key factors in the construction of entrepreneurial identity among farmers. The reason why it should be included: täydentää behavioraalisia rooliodotuksia: ellei usko personal kontrolliin, ei ehkä ole sinnikäs jne. Entrepreneurial identification and success Special interests: they were introduced in the introduction already; -main point : both represent the social value of being an entrepreneur: in positive and negative aspects; success: positive: good success: self-esteem, admiration, all that, if failure: threeat to self-esteem, halveksuntaa, this is the psychological and social risk in enterprise, ; if strong identification, both em are intensified, if weak identification, might be either a hinder for pursuit (motivation etc selfconfidence,) or as well a avoidance of psychological and social risk in other words: the expressive order is most clearly involved in the role xpectances, that why we are interested in them -to call onself as one -also: to express willingness to do so, -to think of onself as a good, fitting member of the category, Success may seem a trivial notion in the context of business but it is still fundamental. Success may mean different things for different entrepreneurs (Ray & Trupin 1989) but at least some level of economic success is a premise. Failure is not hoped for,. The possibility of failure inbuilt in business ownership underlines the importance of success. The expectation of success in itself may not differentiate entrepreneurs from small business owners, but much of the theorizing in the study of entrepreneurship seem to imply that the more successful a small business owner is, the more entrepreneurial he/she is. The subjective perception of success can be based on different sources of information; the feedback for ones own behaviour, comparisons with other actors etc. On the other hand, optimism – or belief in ones owns success – is a psychological expectation, supposedly motivating the behaviour and persistence in it. . The risk in entrepreneurship is also psychological and social are also Entreprenruial risk different thing. Even economic success means different things for different entrepreneurs (Ray & Trupin). There are many ways to make inferences concerning the success, and the experience of success includes also anticipation of future events, for example, believing in success Research setting -johdannoissa esitetty tutkimuskysymys roolikäsitteillä muotoiltuna (subjektive perspective to the performance, how fits with the ecpectation – how entrepreneurial their performance is vertaamme kolmea ryhmää, yrittäjät toimivat kontrolliryhmänä, jolla arvioidaan mittareiden käsitteellistä validisuutta (discriminant validity) : assumption that farmers ought to be on the average less entrepreneurial, we don’t think that the scales are absolute in the sense that the higher points the more entrepreneurial, -we aim at a description, not explanation , the point is on the comparison -we describe the differences between groups and the try to construct an interpretation how to understand these differences in the context of farm sector, with the help of correlation analysis Data The subjects of the study1 were monoactive farmers, diversified farmers and non-farm small business owners in rural areas. Three nationwide random samples were generated, each representing a broad cross-section of industries. The total number of questionnaires mailed was 3390, with a total of 1238 valid responses received, for a 37% response rate. The response rate for the monoactive farmers was 41% (n=243), for the diversifiers 36% (n=799), and for the small business owners 33% (n=196). The sample of monoactive farmers included grain, milk, and meat producers functioning merely in primary production. The sample of the diversifiers was constructed from 11 different industries: tourism, food processing, handicraft, wood processing, energy production, machine contracting, fur farming, production of metal ware, health services, transportation, and retail trade in farm products. The sample of the small business owners was delimited to small-scale enterprises from trade, industry and service sectors with maximum of 20 personnel and sales more than FIM 49,000 (8240€). The enterprises included had been started at least two years before sampling. The rural area was defined by population density less than 50 persons/km² within a certain zip code. The data were collected on March-June 2001. Measures In the following we will present the measures corresponding to the entrepreneurial role-expectations introduced in the previous chapter. The individual items used in the questionnaire were combined to form the measures. The combinations are based on the evaluation of the conceptual validity as well as the statistical analyses of reliability. The internal consistency was assessed with the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient. Removing items did not enhance the reliability of any of these measures. The questions related to the items and the response scales are presented as well. Entrepreneurial strategy (12 items, alpha .81) “How do the following statements characterize You as an entrepreneur?” (Strongly disagree / partly disagree / not for or against / partly agree / strongly agree) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. I am more cautious with risk-taking compared to other entrepreneurs that I know. I do not avoid taking risks. I take risks only when compelled to do so. I do not believe in success without risk-taking. Increasing the turnover of my firm is a self-evident goal for me. Compared to other entrepreneurs whom I know, I am more reluctant in expanding my business. I prefer not to hire employees in my firm. I am trying to expand my business activities. I aim at constant renewal in my business activities. I enjoy developing new products and marketing ideas. If needed I will make even major changes in my business. I prefer to keep doing things the way I am familiar with. Note! Voidaan jakaa myös innovatiivisuuteen ja kasvuorientaatioon, saadaan samat tulokset niin ryhmien välisten keskiarvojen kuin muiden analyysien osalta. Success (10 items, alpha .78) 1 The survey data was generated in co-operation with Mikkeli Institute of Rural Research and Training/University of Helsinki, the Department of Social Psychology/University of Helsinki, and Agrifood Research Finland. The study was funded by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. “How do the following statements characterize you as an entrepreneur?” (Strongly disagree / partly disagree / not for or against / partly agree / strongly agree) 1. I will succeed as an entrepreneur 2. Not even major setbacks can make me give up my entrepreneurship 3. I believe that my success in the future will outrun entrepreneurs on average 4. My success as an entrepreneur is uncertain Are You or would You be able to compete5. with prices? 6. with quality? 7. with expanding the business? (not at all / to some extent / well / very well) 8. What would you think would be your net profit in the forthcoming year 2003? (Profitable and satisfying / positive but not satisfying / +/-0 / more or less unprofitable / remarkably unprofitable) 9. How has the profitability of your business developed during the years 1997-2000? (increased remarkably / increased to some extent / stayed the same / decreased to some extent / decreased remarkably) 10. How is the profitability of your business going to develop in the years 2001-2003? (will increase remarkably / will increase to some extent / will stay the same / will decrease to some extent / will decrease remarkably) Customer activeness (5 items, alpha .67) 1. Do you engage in active marketing (advertising, making offers etc.) (very much / a lot / to some extent / not much / not at all) 2. Do you discuss or negotiate with your customers? (very much / a lot / somewhat / not little / no at all) 3. To what extent does your working time consist of: - Sales, marketing and other customer work (as one option). In what ways are you going to develop your business in the years 2001-2003? 4. Search for new customers (yes/no) 5. Develop new products or services (yes/no) (as part of other options) Entrepreneurial identification (7 items, alpha .74) 1. “How apt is it in your case to think at the moment: I am an entrepreneur?” (not likely at all / not very likely / cant say / partly likely / very likely) 2. “How did it feel in the beginning of your career to think: I will be an entrepreneur?” (not desirable at all / not very desirable / cant say / somewhat desirable / very desirable) 3. “How desirable would it be for you to think in the future: I am an entrepreneur?” (not desirable at all / not very desirable / cant say / somewhat desirable / very desirable) “How do the following statements characterize you as an entrepreneur?” (Strongly disagree / partly disagree / not for or against / partly agree / strongly agree) 4. My skills are quite sufficient for working as an entrepreneur. 5. I am more competent than an average entrepreneur. 6. My character is not of entrepreneurial type. 7. My personal characteristics suit well for entrepreneurship. Personal control (6 items, alpha .80) “How do the following statements characterize you as an entrepreneur?” (Strongly disagree / partly disagree / not for or against / partly agree / strongly agree) 1. I am able to affect the success of my firm through decisions concerning products and through production. 2. My personal chances to influence the successfulness of my business are practically rather low. 3. I am able to affect the success of my firm through marketing and customer connections. 4. To a great extent I can personally control the success of my firm. 5. Success of my business depends on me. 6. Success of my business depends on the relationships and interaction between me and other people. Entrepreneurial values (5 items, alpha .72) How important do you think the following principles are in your business activity? (cant say / not meaningful / somewhat meaningful / very meaningful / extremely meaningful) 1. Autonomy in one’s work. 2. One’s own economical independency. 3. Maximization of profit. 4. Earning better standard of living for one’s family and oneself. 5. The profitability of one’s business. Results Description of the sample groups The questionnaire covered biographical data on age, sex, marital status and education. The enterpriserelated questions covered firm’s turnover, number of non-family employees and number of customers and products. The descriptive statistics in the sample groups are shown in table 1. The group comparisons were conducted with χ²-tests, which are reported in the fifth and sixth column on table 1. On average, the small business owners were older and had more business-related education than the other groups. The proportion of women was highest (31%) within the small business owners Table 1. Biographical variables within small business owners, diversifiers and monoactives. 1 small business owners (n=196) 2 diversifiers 3 monoactives variable (n=799) Age 20-39 years 16 29 40-49 years 41 38 50-74 years 43 33 Sex woman 31 15 man 69 84 Business-related education yes 79 66 * p<.05 ** p<.01 *** p<.001 ns.=non-significant (n=243) 24 35 41 1-2 χ² 2-3 χ² 15,2*** ns. 26,0*** ns. 11,2** ns. 13 87 64 Instead, the differences in the enterprise-related variables (Table 2) were clear-cut between the diversifiers and monoactive farmers. Measured whether with the sales turnover or with the number of non-family employees, the diversifiers’ businesses were larger than the monoactive farmers’. The number of customers as well as the number of products was also significantly higher within the diversifiers. Nevertheless, compared to the small business owners the diversifiers were still smallscaled and they had fewer customers and co-operative partners than the small business owners. In the number of products there were no statistically significant difference between the diversifiers and small business owners. Taken together, the group differences were substantial in the enterprise-related factors, the diversifiers being in the middle of the other groups. Table 2. Enterprise-related variables within small business owners, diversifiers and monoactives. 1 ownersmanagers (n=196) 2 diversifiers (n=799) variable Revenue year 2001 (€) 41 23 < 42 000 40 22 42 000 - 168 000 19 54 > 168 000 Number of non-family employees 45 33 none 37 20 1-2 18 47 >2 Number of products 25 26 1 31 28 2 20 17 3 23 29 >3 Number of customers 23 9 one or few 11 12 4-9 25 20 10-50 41 59 > 50 Number of co-operative partners 46 35 none 33 27 1-2 22 38 >2 * p<.05 ** p<.01 *** p<.001 ns.=non-significant 3 conventional farmers (n=243) 1-2 χ² 92,0*** 2-3 χ² 19,1*** 66,6*** 40,8*** ns. 43,4*** 26,5*** 251,9*** 19,5*** ns. 41 51 8 69 26 5 37 43 15 6 82 7 5 5 53 28 19 The differences between the groups seem to be quite understandable. Diversifier are farmers who have started also other business. The background of the diversifiers is similar to farmers, but the difference is on the enterprise. ?? Differences indicate that there are rather concrete differences between the groups in the situation of the actor. ?? Differences in the role performance Our main research question was whether the entrepreneurial role-expectations are fulfilled in the same extent within the different sample groups? Are there differences between monoactive farmers and diversifiers? Are the diversifiers as entrepreneurial as the small business owners? First of all, we did find clear-cut differences between the sample groups, non-farm small business owners being most entrepreneurial and monoactive farmers least entrepreneurial. This general finding is in line with the earlier studies and thus supports the discriminant validity of the measures. The diversifiers were more entrepreneurial than the monoactive farmers. Their role performance compares to small business owners in some aspects, even though they have their weaknesses. We explored the group differences by comparing the diversifiers and monoactives to the group of small business owners. In order to test the statistical significance of the differences we conducted a series of t-tests for independent samples and confirmed them with non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-tests. The mean scores are presented in figure 1, where a circle indicates a statistically significant difference compared to small business owners. As Figure 1 reveals, the mean scores for the monoactive farmers were lowest in each measure. Respectively, the small business owners scored the highest scores on every measure, even though the differences to other groups were not statistically significant in all dimensions. For example, in entrepreneurial values there were no significant differences between the groups – each group value greatly independence and economic profit. Regarding the entrepreneurial strategy, the monoactive farmers scored lower than the other groups. In other words, they did not view themselves as growth-oriented, risk-taking and innovative as the others. Correspondingly, the monoactive farmers had clearly the lowest score in entrepreneurial identification. There was a minor difference between the diversifiers and the small business owners as well, even though no statistically significant difference in mean scores (t=xx, p=.xx), but in median (Z=xx, p=.xx). Further, there were three dimensions, in which the results differed in all of the three groups. The monoactives had the lowest scores also in personal control, success and customer activeness. The group differences were most substantial in the customer activeness. Taken together, the results indicate that the diversifiers are quite entrepreneurial: they value independence and profit, they view themselves as innovative, risk-taking and growth-oriented as the small business owners and they identify themselves as entrepreneurs. Still, they have their weaknesses in personal control, success and customer orientation, compared to small business owners. Figure 1. Small business owners, diversifiers and monoactive farmers in comparison. Mean scores for the measures of entrepreneurial role expectations. 4,50 4,00 3,50 3,00 2,50 2,00 1,50 1,00 entrepreneurial values entrepreneurial strategy entrepreneurial identification small business owners personal control diversifiers success customer activeness monoactives Note. A circle indicates a statistically significant difference (p<.01) compared to the small business owners -all in all, ei eroja arvoissa, eli the performance is as entrepreneurial in all groups. (vrt yeoman, voisi olettaa eroja,m mutta toisaalta on esitetty, että ovat eri ulottuuvuksia, as a matter fact, we measured also tehse and the result support the that they are a different dimension -kaikki ryhmät eroavat toisistaan kolmella ulottuuudella, lisäksi monoactiiivt eroavat muista kahdella. ovatko nämä erot yhteydessä toisiinsa ja miten -of perform entrpreneurial selkeimmät/kautta vahvmmat erot ovat asiakasaktiivsuudessa, -ovatko nämä erot itsenäisiä tai erillisiä asioita, yhteydessä toisiinsa, ja jos niin miten, -kun katsotaan rooliodotusten näkökulmasta, voisi olettaa, että menestys on seurausta -voivatko nämä roolisuoritusten erot riippua toisistaan, jos niin miten The relations between different aspects of the role performance So far, we have reached a description of the group differences, but we were as well interested in the associations between those measures. Are the other aspects of role performance associated with success and identification? Table 3. Correlation coefficients between entrepreneurial role expectations. 1. entrepreneurial orientation 2. self-categorization 3. personal control 4. subjective success 5. customer activeness 1 2 3 4 .47*** .40*** .54*** .39*** .40*** .56*** .26*** .59*** .45*** .38*** According to correlation analysis, all the measures presented in figure 1 had a positive correlation with success. All correlations were statistically significant, the strongest correlation was the relation between success and personal control (.59) and the lowest was the relation between success and customer activeness (.38). To examine the relationships between the measures in more detail a series of partial correlations were calculated. The partial correlation coefficient is a measure of the strength of the linear relationship between two variables after controlling for the effects of other variables. Specifically, with partial correlations we examined whether the measures had an independent effect on success and identification. For example, estimating the partial correlation coefficient between personal control and success, we controlled the other factors (i.e. customer activeness and entrepreneurial strategy). Table 4. Partial correlation coefficients between customer activeness, personal control, entrepreneurial strategy and success / entrepreneurial identification. entrepreneurial orientation personal control customer activeness Success Zero-order Partial a .54*** .37*** b .59*** .45*** .38*** .07*c Entrepreneurial identification Zero-order Partial a .47*** .36*** b .40*** .27*** .26*** .00c a. Controlling for personal control and customer activeness. b. Controlling for entrepreneurial strategy and customer activeness. c. Controlling for entrepreneurial strategy and personal control. *** p<.001 ** p<.01 * p<.05 Table 4 shows that both personal control and entrepreneurial strategy had significant partial correlations with the measures of success and entrepreneurial identification, although the magnitude of the correlations was attenuated to some extent (partial correlation compared to the zero-order correlation shown in table 4). Nevertheless, the partial correlations indicate that both factors are useful in accounting for variance in success and their contribution does not depend on the other factors. On the contrary, after adjusting the other factors, the magnitude of the correlation between customer activeness and success was attenuated substantially (rpartial=.07), although it still was statistically significant (p=.0xx). These results indicate, that personal control and entrepreneurial strategy explain in part the association between customer orientation and success. In other words, the relation between customer activeness and success is mediated by personal control and entrepreneurial strategy. Likewise, partial correlations were performed for entrepreneurial identification. The results conform to those got with success. The measures of personal control and entrepreneurial strategy seem to have an independent effect on entrepreneurial identification, as shown in the last column of table 4 (controlling for the other factors, the correlations are still present). Noteworthy, the relation between customer orientation and success disappeared when adjusted for personal control and entrepreneurial strategy. The results suggest, that personal control and entrepreneurial strategy function as mediators also in the relation between customer orientation and entrepreneurial identification. Individual background and enterprise characteristics as determinants of the customer activeness Further, what is the relation of respondent background and enterprise characteristics with the examined measures? Given the mediating role of personal control and entrepreneurial strategy, our focus is on customer activeness, which could be assumed to be associated with the enterprise characteristics. We examined the associations with linear regression analysis. The independent variables were dichotomised for the analyses. The results are presented in table 5. The best regression model was achieved with number of customers, number of products, the turnover of the enterprise, number of cooperative partners and respondent’s sex. All variables were positively associated with customer activity. The model, in which the number of customers was the best individual predictor (beta .35), explained 27% of the variance in customer activeness. Table 5. Predicting customer activeness with biographical and enterprise-related variables. Linear regression analysis. Dependent variable Predictors Customer activeness Number of customers >4 Number of products >2 Revenue >170 000€ N. of co-operative partners >2 sex(male=0, female=1) Model R²=.28; adjusted R²=.27 Discussion and conclusions std. Beta t-value .35 .24 .13 .09 .07 10.80*** 7.29*** 3.83*** 2.73** 2.23* -tulos I: eroja löytyi ryhmien välillä, arvoissa ei muilla ulottuvuuksilla kyllä farmers vähiten entrepreneurial , diversifiers enemmän, (vrt Carter, ym) mutta näilläkin vaikeuksia toteuttaa yrittäjän rooliodotuksia kolmella ulottuvuudella (kolmen tekijän kommentointi: personal control -tulos II: identifiointi, on eroja, on yhteydessä muihin tekijöihin, mutta asiakasaktiivisuuteen välillisesti, -tulos III: success, on eroja, on yhteydessä muihin tekijöihin, mutta asiakasaktiivisuuteen välillisesti, -figure -lisäpointteja: kysymys ei ole vain taloudelliseen tavoitteluun suoraan liittyvästä roolisuorituksesta, vaan myös vahvoja sosiaalisia imlikaatioita sisältävät identiteetti ja menestyskokemus pelissä mukana -nämä tekijät kyllä määrittyvät tavoittelusta: strategia ja personal kontrolli suoraan kytkennässä näihin, mutta asiakasaktiivisuus välillisesti; asiakasaktiivisuudella taas vahva kytkentä as.lukumäärään ja kokoon, -> siis tilanne, toiminta ja sos. kokemus kaikki liittyvät rooliesitykseen -huom: ei siis yksisuunt. selitys vaan kuvaus näiden tilanteesta yrittäjänä, minkälaisia prosesseja mukana -mv ja monialaisten ero: farmers; useita vajeita, monialaisilla vielä ongelmana: personal control, success, Figure 2. References Figure 2. The group differences in entrepreneurial role expectations, statistically significant differences. entrepreneurial values entrepreneurial strategy entrepreneurial identification personal control success customer activeness small business owners vs. diversifiers diversifiers vs. monoactives small business owners vs. monoactives ns. ns. ns. *** ** *** ns. *** *** *** *** *** ns. *** *** *** *** *** Figure 3. Partial correlations between customer activeness, personal control, entrepreneurial strategy and entrepreneurial identification.