MOBY Biography 2011 Creative history is littered with insomniac

advertisement

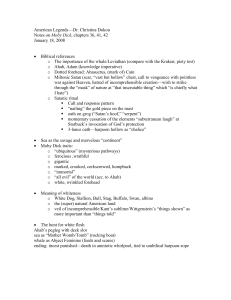

MOBY Biography 2011 Creative history is littered with insomniac icons – Vincent van Gogh, Marcel Proust, Charles Dickens, Groucho Marx, Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe and David Bowie to name but seven, all of whom were regularly kept from the tender embraces of Morpheus by over-stimulated brains and artistic appetites that just wouldn’t quit. Vegan, teetotal and habitually brimming with rude health though he is, Moby is another major artist to add to the role-call of the illustrious but slumber-free, even if, for him, sleep deprivation is as much about the modern international music star’s peripatetic lifestyle as it is an unquenchable creative dynamo. Moby, it transpires, is a martyr to his circadian rhythms. “The last thing I should be is a travelling musician,” he admits. “Some friends of mine, if they go from Los Angeles to London they’re immediately on British time; or they go from Singapore to San Francisco and they’re immediately on San Francisco time. I, unfortunately, go from New York to London and sit in my hotel room not sleeping for hour after hour.” Rather than twiddling his thumbs during such protracted periods of wired somnambulance, however, Moby has come to embrace enforced wakefulness and turn it to his advantage – a process he calls “repurposing insomnia.” Aside from learning to relish “some amazing sunrises you wouldn’t normally see … stuff that’s hidden from the sleeping world”, during his last world tour he carried with him a laptop Pro Tools setup, a microphone and keyboard and for the first time began to write and record music on the road. The bleary, after-hours statelessness of the touring regimen, and the awed solitude inherent in gazing out upon silent urban nightscapes, pervade his new compositions, imbuing them with an ambiguous, liminal quality, seemingly oscillating between ennui, consolation and epiphany. It’s a fuzzier, woozier strain of the ‘elegant melancholy’ which has characterised much of Moby’s best-loved music; a rare quality in a musician still affiliated, however nominally, with the extrovert escapism of dance music. “You’re in Cologne, in a hotel, room, you have insomnia, you’re exhausted but you can’t sleep; you look out of your window and everything as far as you can see is quiet and asleep, except for the occasional changing street light”, Moby says, outlining Destroyed’s quintessential mise-en-scène. “You’re hardly going to make jump up and down, feel-good music… I certainly tend to make music [in that environment] that’s quieter, more atmospheric, a little disconcerting but hopefully a little warm, enveloping and beautiful at the same time.” With a hard drive full of these evocative, wee small hours recordings, Moby returned to his studio in downtown Manhattan (New York being ‘the city that never sleeps’ after all – which is perhaps why Moby has recently relocated to Los Angeles, although he maintains his NYC facility) where he set about fleshing out the sketches into full-blown songs. The result is Destroyed, Moby’s ninth studio album, a 15-track collection that, sure enough, conflates the atmospheric and the disconcerting with the enveloping and beautiful. Rich in the kind of melodies that are lodged in the brain by stealth rather than with a bludgeon, it is nonetheless a record whose hook-line quotient is arguably unrivalled in the Moby canon since his 1999 international breakthrough album, Play. Like its predecessor, 2009’s post-punk-indebted Wait For Me, the new album eschews deluxe studio gloss in favour of warts-and-all charm, inspired particularly by proto-electronic pioneers such as Suicide, DAF and early Heaven 17 – artists whose flawed but fearless attempts to capture electronic instruments resulted in music of immense character, filled with the kind of raw, sonic grain which a rueful Moby doesn’t hear in too much contemporary music. “I don’t really like too many big, well-produced records. I tend to like old records, whether it’s a Billie Holiday or John Lee Hooker recording … even a record like Cream’s Disraeli Gears: you listen to the [technical quality of the] recording, and it’s disastrous – but it sounds and feels amazing. What I love about John Lee Hooker’s first single, ‘Boogie Chillen’’, is that it’s just a guitar, a vocal and a guy hitting a box, and it leaves room for me, the listener, to enter the recording; whereas I listen to a new pop record and its so big, so bombastic and over the top and so perfectly produced, I feel like I’m at an incredibly loud, dynamic party that I’m not invited to.” While it’s undoubtedly a record with a generosity of sonic space and some of the dirt left in, Destroyed is also a thing of liquid texture and multidimensional allure, featuring a cabal of seductively-toned female guest singers (Moby, who admits to not favouring his own singing voice, restricts himself to a handful of, nonetheless impressive, vocals, typically processing them through a half-broken Korg vocoder). With often dissonant, minimalist introductions inexorably ceding to, sometimes epic, crescendo choruses, it’s an album which, for all its musical smarts and sonic flourishes, allows its disconnected provenance to show through. “The trajectory of a lot of the songs is sort of like the trajectory of hotel insomnia”, Moby elucidates. “It starts out disconcerting and then you sort of make peace with it. The more time goes, the more you realise that it’s not disconcerting, it’s actually quite interesting. [Likewise] the songs begin minimal and fractured and then build and fill in a little bit.” Ranging discreetly across styles, from the Kraftwerkian vocoders and pointillist electronica of ‘The Broken Places’ and the soaring, hymnal ‘Be The One’, to the soulful funk of ‘The Right Thing’ via the Bowie/Eno-indebted ‘The Day’, the unadulterated synth-pop of ‘Blue Moon’ and the symphonic melancholy of ‘Lie Down In Darkness’, Destroyed offers a nonetheless homogenous listening experience – one designed to be consumed, Moby insists, as an album. “This might sound bad, but when I was growing up, albums were some of my best friends. Heaven Up Here by Echo and the Bunnymen and Closer by Joy Division: I was closer to these records than I was to my family and friends. I love the [idea of the] album as a cohesive body of work; it’s still really precious to me. Published simultaneously with the album is a deluxe art tome of Moby photographs, also titled Destroyed. The book offers a by turns stark, poignant, amusing and beautiful cavalcade of surreally deserted cityscapes and urban ‘non-places’, airport buildings with endless corridors that seem to lead nowhere, and semi-abstract compositions of cloud forms and landscapes shot from airplane windows. There are also several contrasting images of luminous but lonely hotel room vistas (“…where the streetlights are all on but are only illuminating emptiness”) set alongside vast, swaying, ‘single organism’ audience shots, as snapped from the stage; their juxtaposition seemingly saying everything about the bizarre psychological dislocation, the dramatic yin and yang, that is the international musician’s life. As Moby puts it, “Touring is all contrasts and strangeness, and that's what I'm trying to convey in these pictures.” The title and front cover of Destroyed, both album and book, are products of Moby’s keen photographer’s eye. The eyecatching image depicts the final part of an LED security warning: Unattended luggage will be destroyed, which Moby snapped as it flashed up, one word at time, in a deserted hallway at New York’s La Guardia airport. The word ‘destroyed’ had an immediate resonance. What might be an elliptical nod to Pablo Picasso’s infamous aphorism, "Every act of creation is first an act of destruction", for Moby is principally an expression of the psychological state bought about by life in almost perpetual motion. “Anyone who’s travelled a lot, or even a little, will have experienced being in an airport, in a hotel, when everything around you is vaguely familiar but disconcerting in its familiarity. You’re in an airport in Singapore and all looks normal, except your circadian rhythms are all screwed up; you haven’t eaten well; you haven’t slept; it’s unnecessarily bright, you’re covered in that weird, synthetic travel grime … and there’s that feeling of just being ‘destroyed’. Sometimes you get past the level of exhaustion and it starts to feel good … the narcotic quality of feeling ‘destroyed’” Moby had to be cajoled into publishing his photographic work by trusted friends from the New York and LA artistic communities, so reluctant was he not to be tarred with the brush of pop star dilettantism. In fact, he is far from being a flashin-the-pan, digital camera-wielding dabbler, having studied film and photography at SUNY Purchase (State University of New York) in his youth. Indeed, Moby has actually been a keen SLR lensman ever since, as a ten year old, he was presented with A Nikon F camera as a Christmas present by his uncle Joseph, a photographer for The New York Times. “It was the single best present. I couldn’t believe I was being given this piece of adult technology. I treated it so reverentially. And then he gave me his old darkroom equipment that he wasn’t using, so I learned how to process my own film and print.” At SUNY Purchase, Moby became a habitué of the college darkroom. “I was obsessive. The darkroom opened at two in the afternoon. I would shoot in the morning, until 1.59pm, and then spend ten hours in the darkroom. I was constantly sick, because developing chemicals are disgusting. That’s one of the great things about digital photography; it’s nice not to be around those toxic chemicals any more.” Photographer, international music star, DJ and soundtrack composer (his credit appears on over 300 Hollywood and arthouse movies; not least Paul Haggis’s The Next Three Days, which boasts Destroyed track ‘Be The One’ on its soundtrack. Alongside other Moby material), Moby is also a lover of great American literature – his great, great grand-uncle was Moby Dick author Herman Melville, after all. Indeed, evocative titles drawn from Moby’s favourite literary works are another hallmark of Destroyed, the album. The song ‘Lie Down In Darkness’ is named after a William Styron novel, for example, while the ‘The Violent Bear It Away’ and ‘Victoria Lucas’ salute Flannery O’Connor’s so-named Southern Gothic morality tale and Sylvia Plath’s first pen-name, respectively’. So, while modesty might prevent him admitting as much, Moby is really something of a modern creative polymath. The scion of a versatile artistic family, he admits to having arrived at music almost by default. “My uncle was a sculptor, so I couldn’t be a sculptor; my mom’s a painter, so I couldn’t be a painter; my other uncle’s a photographer... They’d cornered those markets, so I had to choose music…” With the dual-discipline Destroyed, Moby has proved that such restrictive notions have been jettisoned. Safe in that knowledge perhaps he’ll finally get a decent night’s sleep now. He surely deserves it. Stay Loose / matt@stayloose.co.uk / mob: 07939 527 656 / office: 0117 9736 558 / downloadable assets: www.stayloose.co.uk