Forster on

advertisement

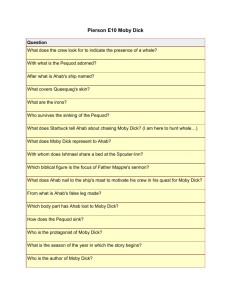

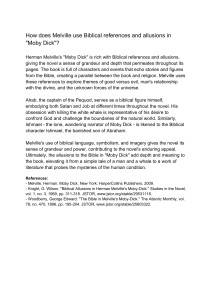

E. M. Forster on Moby Dick and Prophecy from Aspects of the Novel (1927) Moby Dick is an easy book, as long as we read it as a yarn or an account of whaling interspersed with snatches of poetry. But as soon as we catch the song in it, it grows difficult and immensely important. Narrowed and hardened into words the spiritual theme of Moby Dick is as follows: a battle against evil conducted too long or in the wrong way. The White Whale is evil, and Captain Ahab is warped by constant pursuit until his knight-errantry turns into revenge. These are words—a symbol for the book if we want one—but they do not carry us much further than the acceptance of the book as a yarn—perhaps they carry us backwards, for they may mislead us into harmonizing the incidents, and so losing their roughness and richness. The idea of a contest we may retain: all action is a battle, the only happiness is peace. But contest between what? We get false if we say that it is between good and evil or between two unreconciled evils. The essential in Moby Dick, its prophetic song, flows athwart the action and the surface morality like an undercurrent. It lies outside words. Even at the end, when the ship has gone down with the bird of heaven pinned to its mast, and the empty coffin, bouncing up from the vortex, has carried Ishmael back to the world—even then we cannot catch the words of the song. There has been stress, with intervals: but no explicable solution, certainly no reaching back into universal pity and love; no “Gentelmen, I’ve had a good dream.” The extraordinary nature of the book appears in two of its early incidents—the sermon about Jonah and the friendship with Queequeg. The sermon has nothing to do with Christianity. It asks for endurance or loyalty without hope of reward. The preacher “kneeling in the pulpit’s bows, folded his large brown hands across his chest, uplifted his closed eyes, and offered a prayer so deeply devout that he seemed kneeling and praying at the bottom of the sea.” Then he works up and up and concludes on a note of joy that is far more terrifying than a menace. […] Immediately after the sermon, Ishmael makes a passionate alliance with the cannibal Queequeg, and it looks for a moment that the book is to be a saga of blood-brotherhood. But human relationships mean little to Melville, and after a grotesque and violent entry, Queequeg is almost forgotten. Almost—not quite. Towards the end he falls ill and a coffin is made for him which he does not occupy, as he saves Ishmael from the final whirlpool, and this again is no coincidence, but an unformulated connection that sprang up in Melville’s mind. Moby Dick is full of meanings: its meaning is a different problem. It is wrong to turn the Delight or the coffin into symbols, because even if the symbolism is correct, it silences the book. Nothing can be stated about Moby Dick except that it is a contest. The rest is song.