Inferior good - Installation is NOT complete

advertisement

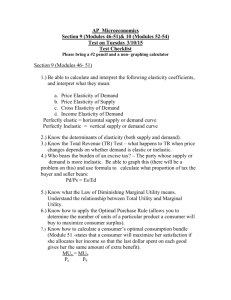

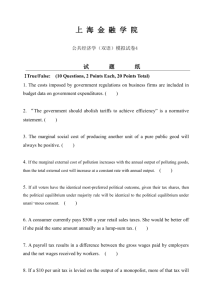

960729 homework4 31. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In economics, the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) is the least-favorable rate at which an agent is willing to exchange units of one good or service for units of another. The MRS measures the value that the consumer places on one extra unit of a good or service, where the opportunity cost is quantified by amount of another sacrificed. Textbook Definition: The rate at which a customer is ready to give up a product A in exchange for product B , total satisfaction remaining the same is termed marginal rate of substitution of B for A Marginal rate of substitution as the slope of indifference curve Under the standard assumption of neoclassical economics that goods and services are continuously divisible, the marginal rates of substitution will be the same regardless of the direction of exchange, and will correspond to the slope of an indifference curve (more precisely, to the slope multiplied by -1) passing through the endowment in question, at that endowment. Further on this assumption, or otherwise on the assumption that utility is quantified, the marginal rate of substitution of good or service X for good or service Y (MRSxy) is also equivalent to the marginal utility of X over the marginal utility of Y. Formally, For example, if the MRSxy=2, the consumer will give up 2 units of Y to obtain 1 additional unit of X. As one moves down a (standardly convex) indifference curve, the marginal rate of substitution decreases (as measured by the absolute value of the slope of the indifference curve, which decreases). This is known as the law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution. Since the indifference curve is convex with respect to the origin and we have defined the MRS as the negative slope of the indifference curve, Normal good 1 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In economics, normal goods are any goods for which demand increases when income increases, i.e. with a positive income elasticity of demand. The term does not refer to the quality of the good. Depending on the indifference curves, the amount of a good bought can either increase, decrease, or stay the same when income increases. In the diagram below, good Y is a normal good since the amount purchased increases from Y1 to Y2 as the budget constraint shifts from BC1 to the higher income BC2. Good X is an inferior good since the amount bought decreases from X1 to X2 as income increases. Inferior good From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In consumer theory, an inferior good is a good that decreases in demand when the consumer's income rises, unlike normal goods, for which the opposite is observed. Inferiority, in this sense, is an observable fact rather than a statement about the quality of the good. As a rule, surfeit is easily achieved with such goods, and as more costly substitutes that offer more pleasure or at least variety become available, the use of the inferior goods diminishes. Inter-city bus service is an example of an inferior good. This form of transportation is cheaper than air or rail travel, but is more time-consuming. When money is constricted, traveling by bus becomes more palatable, but when money is more abundant than time, more rapid transport is preferred. 2 Luxury good From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A luxury sedan is an example of a luxury good. In economics, a luxury good is a good for which demand increases more than proportionally as income rises, contrast with inferior good and normal good. Luxury goods are said to have high income elasticity of demand: as people become more wealthy, they will buy more and more of the luxury good. This also means, however, that should there be a decline in income its demand will drop. It must be noted, though, that income elasticity of demand is not constant with respect to income, and may change sign at different levels of income. That is to say, a luxury good may become a normal good or even an inferior good at different income levels, e.g. a wealthy person stops buying increasing numbers of luxury cars for his automobile collection to start collecting airplanes (at such an income level, the luxury car would become an inferior good). Giffen good From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A Giffen good is an inferior good for which a rise in its price makes people buy even more of the product as a consequence of the income effect. Evidence for the existence of Giffen goods is limited, but there is an economic model that explains how such a thing could exist. Giffen goods are named after Sir Robert Giffen, who was attributed as the author of this idea by Alfred Marshall in his book Principles of Economics. 3 For most products, price elasticity of demand is negative. In other words, price and demand pull in opposite directions; if price goes up, then quantity demanded goes down, or vice versa. Giffen goods are an exception to this. Their price elasticity of demand is positive. When price goes up, the quantity demanded also goes up, and vice versa. In order to be a true Giffen good, price must be the only thing that changes to get a change in quantity demand, and conspicuous consumption does not enter the picture (such a situation would indicate a Veblen good). The classic example given by Marshall is of inferior quality staple foods, whose demand is driven by poverty that makes their purchasers unable to afford superior foodstuffs. As the price of the cheap staple rises, they can no longer afford to supplement their diet with better foods, and must consume more of the staple food. Marshall wrote in the 1895 edition of Principles of Economics: As Mr. Giffen has pointed out, a rise in the price of bread makes so large a drain on the resources of the poorer labouring families and raises so much the marginal utility of money to them, that they are forced to curtail their consumption of meat and the more expensive farinaceous foods: and, bread being still the cheapest food which they can get and will take, they consume more, and not less of it. Giffen goods are also related to experience goods and credence goods in that the two often exhibit increases in demand with price, yet different in that close substitutes are available for the latter types. Durable good From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A car (Toyota Corolla S) is a durable good in economics. In economics, a durable good or a hard good is a good which does not quickly wear out, or more specifically, it yields services or utility over time rather than being completely used up when used once. 4 Most goods are therefore durable goods to a certain degree. Perfectly durable goods never wear out. As an example, a rubber band is not very durable. Examples of durable goods include cars, appliances, business equipment, electronic equipment, home furnishings and fixtures, houseware and accessories, photographic equipment, recreational goods, sporting goods, toys and games. Durable goods are typically characterized by long interpurchase times (Next product to buy models). Nondurable goods or soft goods are the opposite of durable goods. They may be defined either as goods that are used up when used once, or that have a lifespan of less than 3 years. Examples of nondurable goods include cosmetics, food, cleaning products, office supplies, packaging and containers, paper and paper products, personal products, rubber, plastics, textiles, clothing, footwear and most services. Durable goods, nondurable goods and services together constitute the consumption of an economy. Price elasticity of demand From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In economics and business studies, the price elasticity of demand (PED) is an elasticity that measures the nature and degree of the relationship between changes in quantity demanded of a good and changes in its price. Introduction When the price of a good falls, the quantity consumers demand of the good typically rises--if it costs less, consumers buy more. Price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of a change in quantity demanded for a good or service to a change in price. Mathematically, the PED is the ratio of the relative (or percent) change in quantity demanded to the relative change in price. For most goods this ratio is negative, but in practice the elasticity is represented as a positive number and the minus sign is understood. For example, if for some good when the price decreases by 10%, the quantity demanded increases by 20%, the PED for that good will be 2. When the PED of a good is greater than one in absolute value, the demand is said to be elastic; it is highly responsive to changes in price. Demands with an elasticity less than one in absolute value are inelastic; the demand is weakly responsive to price changes. 5 [edit] Interpretation of Elasticity Value n=0 Meaning Perfectly inelastic. 0 < n < 1 Relatively inelastic. n=1 Unit elastic. 1 < n < ∞ Relatively elastic. n=∞ Perfectly elastic. For all normal goods and most inferior goods, a price drop results in an increase in the quantity demanded by consumers. The demand for a good is relatively inelastic when the quantity demanded does not change much with the price change. Goods and services for which no substitutes exist are generally inelastic. Demand for an antibiotic, for example, becomes highly inelastic when it alone can kill an infection resistant to all other antibiotics. Rather than die of an infection, patients will generally be willing to pay whatever is necessary to acquire enough of the antibiotic to kill the infection. Price elasticity of demand is rarely constant throughout the ranges of quantity demanded and price. A good or service can have relatively inelastic demand up to a certain price, above which demand becomes elastic. Even if automobiles, for example, were extremely inexpensive, parking or other related ownership issues would presumably keep most people from owning more than some "maximum" number of automobiles. For these and other reasons, elasticity of demand remains valid only over a specific (and small) range of price. Demand for cars (as well as other goods and services) is not elastic or inelastic for all prices. Elasticity of demand can change dramatically across a range of prices. Inelastic demand is commonly associated with "necessities," although there are many more reasons a good or service may have inelastic demand other than the fact that consumers may "need" it. Demand for salt, for instance, at its modern levels of supply is highly inelastic not because it is a necessity but because it is such a small part of the household budget. (Technology has increased the supply of salt modernly and reduced its historically high price.) Demand for water, another necessity, is highly inelastic for similar supply side reasons. Demand for other goods, like chocolate, which is not a necessity, can be highly elastic. Substitution serves as a much more reliable predictor of elasticity of demand than "necessity." For example, few substitutes for oil and gasoline exist, and as such, demand for these goods is relatively 6 inelastic. However, products with a high elasticity usually have many substitutes. For example, potato chips are only one type of snack food out of many others, such as corn chips or crackers, and predictably, consumers have more room to turn to those substitutes if potato chips were to become more expensive. It may be possible that quantity demanded for a good rises as its price rises, even under conventional economic assumptions of consumer rationality. Two such classes of goods are known as Giffen goods or Veblen goods. Another case is the price inflation during an economic bubble. Consumer perception plays an important role in explaining the demand for products in these categories. A starving musician who offers lessons at a bargain basement rate of $5.00 per hour will continue to starve, but if the musician were to raise the price to $35.00 per hour, consumers may perceive the musician's lessons ability to charge higher prices as an indication of higher quality, thus increasing the quantity of lessons demanded. Various research methods are used to calculate price elasticity: Test markets Analysis of historical sales data Conjoint analysis [edit] Mathematical definition The formula used to calculate the coefficient of price elasticity of demand is Or, using the differential calculus: or alternatively: where: P = price Q = quantity Qd = original quantity Pd = original price ΔQd = Qdnew - Qdold ΔPd = Pdnew - Pdold One caveat in using this (valid) formula: Will you use the original or the new quantity demanded in the denominator? Will you use the original or new price in the denominator? Be consistent at least and use one set or the other. A more elegant and reliable calculation uses a midpoint analysis--instead of the original or the new, try using the point half way between the two for your calculations. 7 Interestingly, repeated use of the chain rule reveals that: From the following process: Note: Further Note: Implying: Substitution reveals: http://www.tutor2u.net/economics/content/topics/elasticity/income_elasticity.htm Marginal revenue From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In microeconomics, Marginal Revenue (MR) is the extra revenue that an additional unit of product will bring a firm. It can also be described as the change in total revenue/change in number of units sold. More formally, marginal revenue is equal to the change in total revenue over the change in quantity when the change in quantity is equal to one unit (or the change in output in the bracket where the change in revenue has occurred) This can also be represented as a derivative. (Total revenue) = (Price) times (Quantity) or . Thus, by the product rule: 8 . For a firm facing perfectly competitive markets, price does not change with quantity sold ( ), so marginal revenue is equal to price. For a monopoly, the price received will decline with quantity sold ( ), so marginal revenue is less than price. This means that the profit-maximizing quantity, for which marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost will be lower for a monopoly than for a competitive firm, while the profit-maximizing price will be higher. When marginal revenue is positive, price elasticity of demand [PED] is elastic, and when it is negative, PED is inelastic. When marginal revenue is equal to zero, price elasticity of demand is equal to 1. Marginal cost From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In economics and finance, marginal cost is the change in total cost that arises when the quantity produced changes by one unit. Mathematically, the marginal cost (MC) function is expressed as the derivative of the total cost (TC) function with respect to quantity (Q). Note that the marginal cost may change with volume, and so at each level of production, the marginal cost is the cost of the next unit produced. 9 A typical Marginal Cost Curve In general terms, marginal cost at each level of production includes any additional costs required to produce the next unit. If producing additional vehicles requires, for example, building a new factory, the marginal cost of those extra vehicles includes the cost of the new factory. In practice, the analysis is segregated into short and long-run cases, and over the longest run, all costs are marginal. At each level of production and time period being considered, marginal costs include all costs which vary with the level of production, and other costs are considered fixed costs. It is a general principle of economics that a (rational) producer should always produce (and sell) the last unit if the marginal cost is less than the market price. As the market price will be dictated by supply and demand, it leads to the conclusion that marginal cost equals marginal revenue. These general principles are subject to a number of other factors and exceptions, but marginal cost and marginal cost pricing play a central role in economic definitions of efficiency. Marginal cost pricing is the principle that the market will, over time, cause goods to be sold at their marginal cost of production. Whether goods are in fact sold at their marginal cost will depend on competition and other factors, as well as the time frame considered. In the most general criticism of the theory of marginal cost pricing, economists note that monopoly power may allow a producer to maintain prices above the marginal cost; more specifically, if a good has low elasticity of demand (consumers are insensitive to changes in price) and supply of the product is limited (or can be limited), prices may be considerably higher than marginal cost. Since this description applies to most products with established brands, marginal pricing may be relatively rare; an example would be in markets for commodities. A number of other factors can affect marginal cost and its applicability to real world problems. Some of these may be considered market failures. These may include information asymmetries, the presence of negative or positive externalities, transaction costs, price discrimination and others. 10 Short-run From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search In economics, the concept of the short-run refers to the decision-making time frame of a firm in which at least one factor of production is fixed. Costs which are fixed in the short-run have no impact on a firms decisions. For example a firm can raise output by increasing the amount of labour through overtime. A generic firm can make three changes in the short-run: Increase production Decrease production Shut down In the short-run, a profit maximizing firm will: Increase production if marginal cost is less than price; Decrease production if marginal cost is greater than price; Continue producing if average variable cost is less than price, even if average total cost is greater than price; Shut down if average variable cost is greater than price. Thus, the average variable cost is the largest loss a firm can incur in the short-run. Long run From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search It has been suggested that this article or section be merged with Long-run. (Discuss) For other uses of the term, see The Long Run In economic models, the long run time frame assumes no fixed factors of production. Firms can enter or leave the marketplace, and the cost (and availability) of land, labor, raw materials, and capital goods can be assumed to vary. In contrast, in the short-run time frame, certain factors are assumed to be fixed, because there is not sufficient time for them to change. This is related to the long run average cost (LRAC) curve, an important factor in microeconomic models. 11 Long run marginal cost (LRMC) refers to the cost of providing an additional unit of service or commodity under assumption that this requires investment in capacity expansion. LRMC pricing is appropriate for best resource allocation, but may lead to a mismatch between operating costs and revenues. In macroeconomic models, the long run assumes full factor mobility between economic sectors, and often assumes full capital mobility between nations. The concept of long run cost is used in cost-volume-profit analysis and product mix analysis. A famous use of the phrase was by John Maynard Keynes, who said in dry humor, "In the long run, we are all dead." Derived demand From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Derived demand is a term in economics, where demand for one good or service occurs as a result of demand for another. This may occur as the former is a part of production of the second. For example, demand for coal leads to derived demand for mining, as coal must be mined for coal to be consumed. Demand for transport is a good example of derived demand, as users of transport are very often consuming the service not because they benefit from consumption directly (except in cases such as pleasure cruises), but because they wish to partake in other consumption elsewhere. Derived demand applies to both consumers and producers. Producers have a derived demand for employees, the employees themselves are not demanded, rather the skills and productivity that they bring. Tickets are a derived demand for entertainment. Entertainment is the demand being satisfied when a ticket is bought, it is purely a means to an end. The ticket is not an end in itself. The ticket is merely a licence to attend a specified event at a specified time and place. The ticket agency is merely that, an agent of the principal (the event owner) authorised to make a transaction with a prospective attendee on the behalf of the principal. Balance of payments The balance of payments, (or BOP) measures the payments that flow between any individual country and all other countries. It is used to summarize all international economic transactions for that country during a specific time period, usually a year. The BOP is determined by the country's exports and imports of goods, services, and financial capital, as well as financial transfers. It reflects all payments and liabilities to foreigners (debits) and all payments and obligations received from foreigners (credits). 12 Components Blue = countries in current account surplus; Red = countries in current account deficit, 2005 The Balance of Payments for a country is the sum of the current account, the financial account (formerly capital account), and the change in official reserves. [Note: The name of the "capital account" was changed in the US in 1999. It is now referred to as the financial account. [1]] [edit] Current account The current account is the sum of net sales from trade in goods and services, net factor income (such as interest payments from abroad), and net unilateral transfers from abroad. Positive net sales from abroad corresponds to a current account surplus; negative net sales from abroad corresponds to a current account deficit. Because exports generate positive net sales, and because the trade balance is typically the largest component of the current account, a current account surplus is usually associated with positive net exports. The Income Account or Net Factor Income, a sub-account of the Current Account, is usually presented under the headings "Income Payments", as outflows, and "Income Receipts", as inflows. If the Income Account is negative, the country is paying more than it is taking in interest, dividends, etc. For example, the United States' net income has been declining exponentially since it allowed the Dollar's price relative to other currencies to be determined by the market to a point where income payments and receipts are roughly equal. The difference between Canada's Income Payments and Receipts have been declining exponentially as well since its' central bank in 1998 began its' strict policy not to intervene in the Canadian Dollar's foreign exchange. The various subcategories in the Income Account are linked to specific respective subcategories in the Financial account. From here, economists and central banks determine implied rates of return on the different types of capital exchanged in the Financial Account. The United States, for example, gleans a substantially larger rate of return from foreign capital than foreigners from domestic capital. 13 When analyzing the current account theoretically, it is often written as a function X of the real exchange rate, p, domestic GDP, Y, and foreign GDP, Y*. Thus the current account can be written as X(p, Y, Y*). According to theory, the current account X should increase if (1) the domestic currency depreciates (p increases), (2) domestic GDP decreases, or (3) foreign GDP increases. A domestic currency depreciation makes domestic goods relatively cheaper, boosting exports relative to imports. A decrease in domestic GDP reduces domestic demand for foreign goods, lowering imports without affecting exports. An increase in foreign GDP increases foreign demand for domestic goods, increasing exports without affecting imports. Current account = Trade Balance o Net Exports (Exports - Imports) of Merchandise (tangible goods) o Net Exports (Exports - Imports) Services (such as legal and consulting services) + Net Factor Income From Abroad (such as interest and dividends) + Net Unilateral Transfers From Abroad (such as foreign aid, grants, gifts, etc.) [edit] Capital account The capital account used to entitle the section now familiarly known as the financial account. This section usually includes special debt transactions between nations and migrants' goods as they cross a country's borders. 14